telegraphic codes and message practice

scanned code directory

resources

This long-neglected page is in some temporary disarray, as I review and overhaul its contents.

Perhaps resources

is too broad a term, though it’s too late to be changing my primary page names. Items are listed by category, and then chronologically within those categories. I will be changing the categories, and adding as well as deleting entries, as I refresh this page.

contemporary overviews and treatises

other contemporary accounts

telegraphic codes — surveys, directories, etc.

messages

collections

Donald Murray

people

telegraph & telecommunications history

articles, theory

other primary sources (pending)

observations and new additions

- I’m light on cryptography. The codes were cryptography

light

themselves, and it is not their crypto features that most interest me about them. - N. Katherine Hayles has drawn new and broader — by which I mean, beyond the crypto community — attention to telegraphic codes with her How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago, 2012), and its digital companion.

- Tomokiyo Satoshi has written (and continues to develop) a number of articles on historical codes, including one on the evolving regulations of telegraph administrations and their relationship to telegraphic codes (here), and a treatment of

nonsecret

codes. (Nonsecret

codes is a way of characterizing the commercial and other telegraphic and signal codes that interest me.) See his Articles on Historical Cryptography for these and other pieces. - See also Tomokiyo-san’s page (in Japanese) covering Japanese telegraphic codes available mainly through NDL’s Digital Library project, at 日本の電信暗号. An abridged version in English is planned.

- Have removed a

telegraphic codes and literature

section. The topic is close to my heart, and is receiving renewed attention.

contemporary overviews and treatises

very much a work in (slow, belated) progress. mea culpa.

- 1894

About Telegraphic Codes and Cipher Messages

in Chambers’s Journal (June 16, 1894) here (pp 379-381), and my transcription here.The Telegraphic Code, now so essential an adjunct to the foreign correspondence department of every businesshouse...

- 1896

How Cable Codes Are UsedTelegraphic correspondence under the ocean increased. Ingenious arrangements of strange words, each of which caries much secret meaning across the ocean—their use a great saving.

Kansas City Star (2 February 1896) : 16Will provide transcription soon (today is 2 November 2013). It may be one of those articles that surfaces in various newspapers, around the same time, in longer and shorter form as space allowed and interest dictated. Includes this —

There is a man in London named Payne who makes a business of preparing special codes for a percentage of the money he can save a firm in its telegraphic bills. He makes himself thoroughly familiar with the firm’s business, summarizing it on blanks prepared for the purpose and then makes up a combination of words with letters that will tell everything about the business—like putting a barrel of words into a thimble. He will make a word, like sogobag, which means nothing, put 22 before it and 106 at the top of the column in which it is in the code book and it represents four long sentences which the firm uses several times a day in its correspondence. For this ability he is well paid. There are a number of these code makers, more or less successful...

- 1900

Cipher Code Books.

How Secrets are Flashed Safely Over Public Wires. Many Are Very Elaborate — The Government Codes — Some Noted Examples

(From the New York Mail and Express.)

New Orleans Daily Picayune (June 14, 1900) : 7Full transcription below —

The rigging up of a cipher code is said to be the most simple thing in the world—by those who know nothing about it. Those the larger governments possess have taken years to put together, and some of the most competent minds have been employed in their construction. Notwithstanding the claims of many newspapers, there is not a single codebook that fully meets the requirements of newspaper work. During the war with Spain many of the correspondents invented what is known as a blind code, and the representatives of a certain metropolitan daily paper which claims to have the finest code in the business yelled their heads off trying to tall the censor’s attention to the fact that the other fellow was using a blind code. This was because nothing could be found in

the finest code in the business

to convey the ideas of the correspondents of the sheets to their office. The chap with the homemade blind code that cost about six cents worth of labor to make knew how to get his information through every time.A blind code is rigged up in various ways, but the most popular is to wire,

Send me $250,

orHow many words do you want?

which sentences, while simple enough apparently, might meanSampson’s fleet has begun the bombardment of Havana

orThe Texas has been sunk by a Spanish warship,

news of great importance when the censor is wide awake, as censors generally are. Business and government codes have been in use as long as the submarine telegraph, the original high cost of cabling being responsible for their creation. The desire for secrecy has encourage the building of business and official codes more than the mere question of telegraphic tolls.The latest thing in the code lineis the social one. Within the last five years families in society have arranged for their private use. Commodore J. Pierpont Morgan and Mr. John W. Mackay have probably the finest codes extant. They are used exclusively for conveying messages of a family nature. One of the most successful mining operators of America, whose wife and children spend much time abroad, communicates long messages to them daily by means of his private code. He keeps them informed of all the latest society gossip, and they in turn convey to him how, when and where they are being entertained. This particular code book contains 325 pages and is the labor of years, in which all the members of the millionaire’s family took part. It contains the names of the individual members of all the prominent families in society and additions and alterations are constantly made in the work, each side notifying the other by mail of the improvements and increases in groups and characters. A similar book, though of course, entirely different as to the code words and their meanings, was prepared for a railroad and telegraph magnate recently, the printing being done by a downtown firm, which received the contract in a roundabout way. The printer was paid by the general passenger agent of one of the railroads the owner of the code controls, and he did not learn whom the book was really for until some weeks after it was delivered and the type distributed.

The creation of a family code is naturally dangerous where a copy of it is liable to fall in the hands of an outsider who may have access to the messages that pass between the members of the household. The social code being used for land telegraphing, as well as submarine, makes it the more valuable to a dishonest employee.

A butler in the employ of a man interested in oil recently dropped a piece of paper in his employer’s room. The latter picked it up, and was astonished to see that the paper constained abstracts frm the family code book, which was supposed to be locked up in a private safe. The butler was discharged, the code was destroyed and a new one was gotten up. The changing of a code book is not difficult, however, it being possible to move the characters up or down as desired, so that they represent new meanings. In the case of the butler it was found that he was not dishonest, but had copied portions of the book out of curiosity to know what the family was doing.

The private secretary of a Wall Street man, who is interested in all the chief enterprises of the country, was asked today if he had ever seen a family code.

Yes, the outside of one,

said he,but there my observations closed. I just know that it is the proper thing for a man of great wealth to have a book of this description, and I knw that Mr. —— has one, but that is all. It is the only code book belonging to him of which I have no personal knowledge. He has twelve other codes, each representing some particular interests, and I helped him to make most of them. Where an interest is permanent, as for instance railroad shares, it is not difficult to arrange a code book, but where it becomes necessary to read the future to guess what may or may not happen, the compiler of a code needs keen foresight and plenty of imagination. I can readily understand for this reason why it is, that there are so few perfect newspaper code books.

The governments have the most complete code books, because they have been at work on them for centuries. Then, too, the saving of money in telegraphing is not so much a consideration of the governments as the desire to keep official communications secret.

The saving of tolls being out of the question, makes it possible for the governments to use more index words or code characters than the average business house or newspaper can afford. Governments frequently change the arrangement of the code words so as to prevent reading of messages in the event of a copy of the book falling into wrong hands. In the navy the code book on each ship is bound in lead, and is the first thing that is dropped into the sea in the event of possible capture of the craft by the enemy.A professional compiler of code books, who has received as much as $20,000 for one work that took fifty persons three years to compile, said to-day that every business house of any pretensions had a code.

Some of the larger houses,

he added,have a special man for writing code messages. It is mere child’s play to turn the pages and learn what is contained in a cipher message received: the sending is the difficult thing. It is necessary to find in the book code words that explain the situation thoroughly.

Some of the trans-Atlantic steamhip companies have excellent codes. This is particularly so of the White Star Line, notwithstanding the fact that it was not made by a professional code maker. I have seen this book. It was arranged for the most part by Mr. J. Bruce Ismay *, when as a boy his father sent him out to this country to do general office work of the company’s American headquarters at Broadway. He started the book with ciphers as to dates of sailing of intended passengers and the rooms they wanted when returning. He added to it day by day while he remained here and since, until now it has no equal in the steamship world. What it cost him in time, money and labor few realize, but it is only by the expenditure of these that great code books are made.

* (my emphasis) : J. Bruce Ismay (1862-1937 *), was chairman of the White Star Line, and a survivor of the Titanic sinking in 1912.

- 1903

Kaufmännische Telegrammatik.

English Commercialtelegrammar

orcode-science

/ free translation from C. Herb.

London : The Mercantile Publishing Syndicate Ltd. ... ; Amsterdam : J.H. de Bussy ..., [ca. 1903]

[4], II, 146, [2] p. ; 23 cm.

Date from The bookseller (Sept. 10, 1903).

MIT Vail Collection. HE7676.H4713 1903 (only copy known to worldcat)will be providing notes shortly (today is 2 November 2013). Was an important source of Barto (1933, 1934).

- 1921

Practical Uses of Commercial Codes and the Economies Resulting Therefrom.

Mrs. M. D. Scott. Office Appliances 34 : 3 (October 1921) : 21 (3)

hereAdequate, not as thorough as Bentley (four years later). But provides some interesting — though indirect — perspectives —

Too often it is left to a stenographer or clerk to code cablegrams, and the export managers of many of our larger firms do not appreciate the value of certain features of a code that requires intelligent effort to utilize.

Brings to mind at least one passage in Stevie Smith’s Novel on Yellow Paper : Or Work It Out For Yourself (1936) —

In the old days a double-barrelled five-letter code cable would take upwards of six hours to decade. And the boys at the other end weren't as bright at it as we were...

(p19)And this —

An effort is now being made to stabilize the code business and service bureaus are being organized in the larger cities of the United States to that end. These bureaus offer not only service but information of vital interest to the importer and exporter in connection with foreign trade, and in addition to the handling of standard codes cover the compilatin of private codes, the coding and decoding of cablegrams, the deciphering of mutilated code words, as well as information as to rules, regulations and rates of the cable and radio companies...This latter would describe the firm that for a short time issued the Code Creed newsletter on coding and foreign trade.

- 1921

Code Creed.

Four issues at LC :

April 1921 (1:1), May 1921 (1:2), October 1921 (1:3), and November 1921 (1:4).Names associated with Code Creed are Charles Dwight Montague, Louise Waterhouse, Charles P. Montgomery (former Chief of Customs Division, U.S. Treasury Dept.). It included articles (some on international trade), reviews of codes. The reviews were ex-cathedra pronouncements of whether a code adhered to some current idea of best practice, and left out other factors that might affect the utility of a specific code for a specific user, industry, commodity, etc.

My notes on selected comments follow —

April 1921 (1:1)

Essentials of a private code

(12-13, 20) — simplicity, safety, economy. five letter, two letter difference, free from transpositions, and pronounceable; mutilation table; appropriate phrase matter; tablesdistributed throughout the code in their proper alphabetical place;

reviews Universal Trade Code (positive, except for transpositions in 2nd and 3rd, and 3rd and 4th letters).May 1921 (1:2)

How cables are laid

(3-6, +4);Saving in cabling

(11-13), close analysis of savings on messages coded by a public versus a private code; damning review of the Atomic Code.October 1921 (1:3)

review of Wood’s Simplex Self-Checking Code; mentions other three letter codes (including Keegan’s, whichhave been used as far back as 1912;

In the arrangement of phrases and other material in this code the author has continued the out-of-date plan followed by old fashioned code men in that the arrangement is not alphabetical.

approves its material, but not its arrangement of same. also,Typing cable messages

(28-29).November 1921 (1:4)

How cables are operated

(reprinted by courtesy of the Commercial Cable Company; illustrates slip perforated for Cuttriss automatic transmitter); reviews General Telegraph Code, which offers good selection generally, but objectionable (unpronounceable) code words. - 1925

Cables and Cabling : The World’s Routes, with Directions for the Management of a Cable Department

Charles W. R. Hooker, entry in Harmsworth’s Business Encyclopedia and Commercial Educator.

(London, 1925 ?) : 1122-26

transcription here - 1925

Codes : Their Nature and Manipulation

E. L. Bentley, entry in Harmsworth’s Business Encyclopedia and Commercial Educator.

(London, 1925 ?) : 1483-88

transcription hereBentley, himself an important code compiler, authored what is among the best overviews of cable codes.

- 1928

Report on the history of the use of codes and code language, the international telegraph regulations pertaining thereto, and the bearing of this history on the Cortina Report

William F. Friedman (USGPO, 1928)

Google digitization of Michigan copy, now at HathiTrust. - 1933

Economie en Techniek van Codes en Codes-Condensors. Préface de De Uitgever. (Uitgever A. Barto, Zutphen, 1933)

Englished as - 1934

Economy and Technique of Codes and Code-Condensors.

Zutphen (Netherlands), 1934.

LC : HE7669.B3Notes to come (today is 2 November 2013). Here are some, from several years ago —

This is a translation and expansion of the 1933 dissertation. Corrections in this (LC) ccopy are done manually, before binding, evidently (evidence of erasures and retyping)

Hence the evolution of cable telegraphy and the improvement of codes have always strongly influenced each other.

(2);good discussion of ITU rate/wordcount evolution, and of code construction (28ff);

orientation

introduced to indicate one step in theselection

process (29);risk of mutilation with figures is greater than with letters

(33);formation of tables

34-38, discusses three-dimension codes on cards;with other tables the same code word is used to indicate widely different things, or prices of some commodities with sufficient differences to avoid confusion.

(on this, refers to Herb-de Bussy.); condensers pp 56-64; part 2 devoted tostudies about condensers

, loosely;the code word considered as a combination of letter pairs, columns, column groups, complexes and main groups

(86)TOC

Part II Studies about Condensers.

Part I General Survey.

introduction (1);

historical survey (p3);

importance of codes and code-condensers as seen from an economical point of view (19);

construction of simple codes. letter- and figure-codes. family- and private codes. code condensers (28);

formation of tables (34);

Mr. Herb’s numbers (38-41);

includes discussion ofpartical prices

at p37

structure of general commercial codes. branch codes (41);

code-words (45);

secrecy (46);

mutilations (48);

checks (53);

condensers (56).

the principal regulations of the conference at Brussels in 1928 (66);

observations (68);

cipher language (69);

code matter accessible to calculation (60);

7-figure code (70);

ranges with less than 5 letters (71);

ranges of 10 letters (72);

permutations, variations and combinations (74);

ranges of 10 letters, classified with regard to vowels and consonants (78);

ranges of letters in the A-category (79);

anti-logarithmic curve (81);

13 1/2 - and 13 2/3 -- figure code (83);

considerations concerning the composing of an economic figure code (84);

the codeword considered as a combination of letter pairs. columns, column-groups, complexes and main groups (86);

general survey (89);

unemployable and undesirable main-groups (90);

further sorting of material (90);

dividing of the C-column (91);

general survey after sorting (92);

coupled columns (93);

choice of couplings (94);

symbols (95);

different kinds of symbols (95);

ranging of symbols (96);

tables (97);

wiring with two words (98);

wiring with three words (99);

wiring with more words (99);

use as a 14-figure code (100);

examples 101, 102);

use as a 13∏-figure code (104);

use as 13 2/3 figure code (105);

checks and net condensing power (106);

comparison of cable rates before and after first of January 1934 (109);

comparison of charges on the same code wires, according to different rates, by reducing the letter to percentages of present charges according to A-rates (110);

extra applications of the 7-figure code discussed (112);

examples (113);

supplement (115);

tables for coding and decoding (117);

list of consulted works (198);

notes and references (205)Barto also wrote a volume of verse

Barto, C. B. (RABOT [= ps. of C.B. Barto]). Rijp en groen. Gedichten.

Haarlem, Copieerinrichting Geka [c. 1954?]. 72 pp.

(printed on rectos only).A privately printed collection of poetry, much of it alluding to/set in Indonesia. Much more to note here (today is 2 November 2013).

other contemporary accounts

I’m leaving out, for now, the large literature from within the telegraph community — fraternity, really — about outrageous and dangerous (that is, vulnerable to mutilation in transmission) code words. These treatments, often highly charged, touch only on the signal side of telegraphy, although they do relate to the evolving nature of acceptable codewords, and even to the definition of a countable

word. They are not my own primary interest.

For now, let one example serve —

Codes and Codes,

in The Telegraphic Journal (February 1, 1880) : 52-54

here

- 1848

The Telegraph and the Turf

pp 29-32 of Charles Maybury Archer, ed., The London Anecdotes for All Readers : The Electric Telegraph. Popular Authors (London: D. Bogue, 1848)

hereThe race-horse was once a favourite symbol of rapidity ; now, even Pegasus is outstripped; and the achievement of Flying Childers, who went over the four-mile course at Newmarket in six minutes and forty-eight seconds, or at the rate of thirty-five miles an hour, is thrown into the shade. The result of every meet is known in town, and at Tattersall’s, almost before the last horse and jockey are at the goal; thus superseding the fleet posters and pigeons that conveyed the intelligence by the old regime...

- 1873

Telegrams were methodically read for statistical and administrative purposes. See The Telegraph Clearing House, a transcription from Chambers’s Journal October 11, 1873 :...the

Clearing House

was first established in the beginning of 1871, experimentally for the purpose of examining at least one day’s messages in every month of each Postal and Railway Telegraph Office in England and Wales... The work, which chiefly consists in fault-finding, is well within the capacity of the female staff, and has been performed in a very satisfactory manner.Maude Hanson (Mrs Arundel-Colliver) is identified as Superintendent of the female staff in the Postal Telegraph Service’s London Clearing House in this genealogy site devoted to the Hanson-Allen family. Maude was earning an annual salary of about £400 ca 1892.

- 1877

Anthony Trollope, The Young Women at the London Telegraph Office

in Good Words (June 1877) and here, as well as his short StoryThe Telegraph Girl

which appeared in Good Cheer, Christmas Number of Good Words (December 1877) and was collected in Why Frau Frohmann Raised Her Prices; and Other Stories (December 1882).Ellen Moody (who provides the transcription of the Trollope essay) notes that The Girl’s Own Paper contained a number of articles on women’s work, including

Female Clerkships in the Post Office

4:186 (21 July 1883): 663.See also Susan Shelangoskie,

Anthony Trollope and the Social Discourse of Telegraphy after Nationalisation.

Journal of Victorian Culture 14:1 (Spring 2009) : 72-92Abstract presented below, with permission of the author) :

The article examines two periodical works by Anthony Trollope, the non-fiction essay

Young Women at the London Telegraph Office

and the short storyThe Telegraph Girl,

to illuminate their contribution to the public discourse on the telegraph after its nationalisation in 1869. Both texts are read in the context of a wider debate in periodical press over the social merits of the telegraph system. Each text deploys rhetorical strategies used by proponents of the government telegraph, which countered criticisms of nationalisation as a financial debacle and reinforced a framework of value based on social responsibility and the social benefits of the new technology. Trollope focused on female telegraph workers to demonstrate how to stabilise the social application of telegraphy by containing it within the boundaries of dominant cultural and literary narratives. By uniting the theme of paternalistic government with the traditional marriage plot, his two works promote the potential of telegraphic technology for social good. - 1876

Walter Polk Phillips. Oakum Pickings

A Collection of Stories, Sketches, and Paragraphs contributed from time to time to the telegraphic and general press, by John Oakum,A Snapper-Up of Unconsidered Trifles

New York: W. J. Johnston, Publisher, 1876

original at NYPLLove and Lightning (7); Old Jim Lawless (11); Thomas Johnson (16); Little Tip McClosky (21); Stage Coaching (28); Posie Van Duzen (41); Block Island (51); Bad Medicine (57); The Bloodless Onslaught (64); Cap. De Costa (68); Uncle Daniel (75); Summer Recreation (83); The Blue and the Gray (87); An Autumn Episode (91); An Old Man’s Exegesis (99); Departed Days (106); Minor Paragraphs (119-176)

herePhillips was a famed operator, general manager of United Press, and inventor of the Phillips Code. The latter was more like a shorthand for operators than a code dictionary, and was committed to memory by study and use. A transcription of the Phillips Code is available at www.qsl.net/ae0q/phillip1.htm

- 1880

W. J. Johnston. Telegraphic Tales and Telegraphic History

subtitled A popular account of the electric telegraph, its uses, extent and outgrowths.

New York: W. J. Johnston (1880)

here, and transcription of passages on code and message practices here. - 1880

The Storming of Rocky Cottage and Other Matters

being chapter 28 of R. M. Ballantyne (1825-1894), Post Haste; a Tale of Her Majesty’s Mails (1880)

hereBusiness men have therefore fallen on the plan of writing out lists of words, each of which means a longish sentence. This plan is so thoroughly carried out that books like thick dictionaries are now printed and regularly used. — What would you think, now, of

Obstinate Kangaroo

for a message?I would think it nonsense, Phil.

Nevertheless, mother, it covers sense. A Quebec timber-merchant telegraphed these identical words the other day to a friend of mine, and when the friend turned up the words

obstinate kangaroo

in his corresponding code, he found the translation to be,Demand is improving for Ohio or Michigan white oak (planks), 16 inches and upwards.

- 1898

Charles Bright. Submarine Telegraphs: Their History, Construction, and Working

Founded in part on Wünschendorff’s Traitée de Télégraphie Sous-Marine and compiled from authoritative and exclusive sources

London: Crosby Lockwood and Son (1898) (Google Book; original at Stanford)From which these extracts on codes and message practice —

Miscellaneous and Commercial Résumé

Section 7.— Business Systems and Administration —

Codes and Cipher Messages.—As has already been mentioned, one important change which has contributed very much to the increased use of submarine cables during recent years, is the development of a system of private codes. Secret language always took, as it does now, two forms, codes and cipher...

Various methods of building up a private code have been introduced from time to time with explanatory books of reference.* Probably the first was that of Reuter, followed some time after—in 1866—by that of the late Colonel (afterwards Sir Francis) Bolton, R.E.† The Telegraph companies at that time could but accept code on the same terms as ordinary messages. At the Rome International Telegraph Conference of 1870, however, certain regulations were laid down regarding the use of code words; and again at the St Petersburg Conference of 1875. At the latter it was decided that code words should not contain more than ten characters. Words of greater length in code messages are liable to be refused. Some telegraph companies, however, accept them at cipher rates, i.e., three or five characters to a word, according to régime. Subsequently the Bureau of this International Congress was authorised to compile a complete focabulary of the words to be recognised and admitted for code purposes. This vocabulary was duly printed and issued. Fresh editions of it are brought out now and again, and three years after date of issue it becomes obligatory upon all parties to the St Petersburg Convention to abide by it.

* Almost from the very beginning of submarine telegraphy, temporarily improvised forms of codes were used both by Governments and by merchants. On the English land lines code messages were in vogue among the great mercantile firms as early as 1853, if not earlier.

† The telegraph codes of the present day are built on somewhat the same principle as the above. They are improvements mainly in the sense of being perfectly simple instead of extremely complicated — and yet they are equally, if not more, trustworthy, from a secrecy standpoint.

The transmission of submarine code messages is liable to be partially, or entirely, suppressed at any moment by the Government of the country which granted the concession for the cable in question. Moreover, Government messages at all times take precedence (immediately on handing in) before all others. These conditions, under which all such concessions are granted, are very obvious and natural precautions, if only in view of war; indeed, whether expressed as a stipulation or not, it is certain that any Government would be acting within its rights in suppressing code messages at such a time, and would almost certainly exercise this privilege.

From the point of view of the general public, the economy effected by the use of code is often even a more important consideration than its secrecy. A single code word, charged for only at a slightly higher rate than one ordinary word, may be made to convey the sense of a good many.* The telegraph cable thus becomes available for business and other purposes by many people who could not otherwise afford it, and the number of messages which pass over it daily have enormously increased in consequence. And with this increase in the number of them, there has not been the corresponding decrease in their length which might have been anticipated. The public has simply become educated to the more liberal use of the telegraph, and has availed itself of its facilities in the measure and in the spirit in which they have been granted to it. The increase of the total volume of traffic, and of business leading to still greater traffic in the future, has more than compensated the companies for the economies effected by its code-using customers.

* —

The following examples, taken from a certain mercantile code, may be of interest here:

—Code Words Plain English Equivalents Elgin Every article is of good quality that we have shipped to you. Standish Unable to obtain any advances on bills of lading. Penistone Cannot make an offer; name lowest price you can sell at. Coalville Give immediate attention to my letter. Grantham What time shall we get the Queen's Speech? Gloucester Parliamentary news this evening of importance. Forfar At the moment of going to press we received the following. A striking example of the unlimited application of the code principle is the word

unholy,

which was used to express one hundred and sixty words. Another English word, which we cannot recall, was made to stand for no less than two hundred! This is economy with a vengeance.The fact is, but for the code system, the existing number of cables would, in many cases, be quite inadequate for the demands of the present traffic. This remark applies most conspicuously to the case of the North Atlantic, and will be readily understood when it is stated that, whereas prior to the universal recognition and adoption of code transmission, the average length of telegrams used to be thirty-five words, it is now only eleven. In other words, but for the code, the companies might, by now, be asked to transmit more than three times as many words as they are transmitting within the same time. More probably the proportion would not be so great in practice, for reasons already given. But even an addition of only half as many again would be embarrassing to the operators — and, indeed, to all concerned, excepting telegraph engineers and contractors, who would, in consequence, have extra cables to lay.

(175-77)*

Unless, indeed, as it is likely enough would have happened, the absence of code — or its suppression by unwise restrictions on the part of the companies — had starved and stunted the natural development of trade itself. All commercial traffic, practically, is nowadays

coded.

Seeing that this custom began to grow up with the establishment of trans-Atlantic telegraphy, it is difficult now to estimate where we should be without it. - 1905

Railway and Commercial Telegraphy (Fifth Edition, revised and enlarged)

Frederick L. Meyer. Chicago and New York: Rand, McNally & Company, 1905

original at Stanford Universitydetailed, thorough chapters on commercial business, beginning and advanced railway business, technical orders and telegraphic reports.

provides examples of the different kinds of telegrams a clerk might handle, e.g.,

grain, provision, and stock quotation,

or aform for trotting race in four heats;

alsocolumn work

in which, for example, statistics are telegraphed along with a description of a baseball game. - 1898

To provide a simple telegraphic code

Joseph Colin Frances Johnson (1848-?), Getting Gold: A Practical Treatise for Prospectors, Miners, and Students (1898, but several editions)Chapter 11 (Rules of Thumb)

To provide a simple telegraphic code

Buy a couple of cheap small dictionaries of the same edition, send one to your correspondent with an intimation that he is to read up or down so many words from the one indicated when receiving a message. Thus, if I want to sayClaim is looking well,

I take a shilling dictionary, send a copy to my correspondent with the intimation that the real word is seven down, and telegraph —Civilian looking weird;

this, if looked up in Worcester’s little pocket dictionary, for instance, will readClaim looking well.

Any dictionary will do, so long as both parties have a copy and understand which is the right word. By arrangement this plan can be varied from time to time if you have any idea that your code can be read by others.Text at Project Gutenberg and Lateral Science, assembled by Roger Curry, where first encountered.

codes

text

- Jim Reeds provides an elegant overview at commercial telegraphic code books; see also his codes data base.

- The Fred Brandes collection of

lettergroup

andpronounceable word

codebooks seems to have vanished from the ether; will contact Mr. Brandes to learn what's become of that material. - Historic Cryptographic Collection,

Pre-World War I through World War II

National Archives Box List, Records of the National Security Agency, Record Group 457

www.hnsa.org/doc/nara/nsaopendoor.htm

( search through with keywordcommercial

)

scroll down for useful finding aids for cryptographic history at www.hnsa.org/doc/nara/

hosted by Historic Naval Ships Association - N. Katherine Hayles has drawn new and broader — by which I mean, beyond the crypto community — attention to telegraphic codes with her How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago, 2012), and its digital companion.

- Tomokiyo Satoshi has written (and continues to develop) a number of articles on historical codes, including one on the evolving regulations of telegraph administrations and their relationship to telegraphic codes (here), and a treatment of

nonsecret

codes. (Nonsecret

codes is a way of characterizing the commercial and other telegraphic and signal codes that interest me.) See his Articles on Historical Cryptography for these and other pieces. - See also Tomokiyo-san’s page (in Japanese) covering Japanese telegraphic codes available mainly through NDL’s Digital Library project, at 日本の電信暗号. An abridged version in English is planned.

messages

text

- Copper Mine Strike of 1913-1914

Images of actual (coded) telegrams, and typewritten plaintext translations. beautiful project, done by student participants in a Scientific and Technical Communication class at Michigan Technological University, in Houghton, Montana, in Fall 2000.These telegrams were communicated back and forth from late July of 1913 until the end of the strike between James MacNaughton, then Second Vice President of the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company (C & H), Quincy Shaw, the president of the company.

collections

text

- Donald McNicol Collection

at Queens University Library, via library.queensu.ca/webmus/sc/collections_mcnicol.htmDonald Monroe McNicol (1875-1953) was a Canadian-born railway telegrapher who rose to become President of the Institute of Radio Engineers, Chairman of the AIEE Publications Committee, editor of the journal Telegraph and Telephone Age, author of numerous scientific and historical articles, and lecturer at Yale.

Collection of some 1200 items from McNicols’s private library, including

books, pamphlets, journals and archival resources on the experimental history and development, to World War II, of the telegraphic, telephonic and radio sciences.

Items in the collection can be searched via the library’s QCAT catalogue, but not as a separate collection. An author search for McNicol will turn up material on telegraphers’ memoirs, poetry and handwriting; printing telegraphy; McNicol’s scrapbooks, etc. - National Cryptologic Museum

here

adjacent to NSA Headquarters, Ft. George G. Meade, Maryland.The Museum has a reference library that appears to be open to scholars and others. Hidden in a virtual tour page is this :

The library has a very large collection of commercial codebooks. These codebooks were used by all manner of businesses to reduce the costs of cable communications as well as to provide a measure of security for trade secrets. Modern communications and encryption methods have made these books obsolete and are mainly of historical interest.

- Abridged Catalogue and Manual of Telegraphy

J. N. Bunnell and Company, 1920

a exhibit in Duke University’s Emergence of Advertising in America: 1850 – 1920 collection, which includes some advertising ephemera pertaining to telegraphy and telephony.

Donald Murray

Donald Murray (1866-1945) was a successful practical engineer, whose main achievements were in the area of printing telegraphy. He was also a clear-headed (and even riveting) writer on telegraphy, particularly printing telegraphy and the future of the technology. He was forward looking. His 1925 article essentially looks forward to e-mail capability in every business and even home.

biographical and bibliographic information at lu.softxs.ch/mackay/Couples0/C111280.html.

Some publications are listed and (unevenly) described below —

- Murray, Donald. 1902.

How Cables Unite the World.

The World’s Work 4 (July 1902): 2298-2309

hereThe growth of vast systems of submarine telegraphy, with the story of recent achievements in swift automatic transmission.

extract from discussion of

Rates, Codes, and Ciphers

—In the early days the Atlantic Telegraph Company started with a minimum tariff of $100 for 20 words and $5 for each additional word. Later this was reduced to $25 for ten words. It was not till 1872 that a rate of $1 a word was introduced. This word-rate system proved so popular that it was soon adopted universally and since 1888 the cable rate across the Atlantic has been continuously down to 25 cents a word. Rates now range from the 25-cent tariff across the Atlantic to about $5 a word between England and Peru. The average for the whole world is roughly $1 a word. This the Commercial Company proposes to charge from America to the Philippines, as compared with the present rate of $2.35 by the circuitous route across the Atlantic, through the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, across the Indian Ocean and on to Manila via Hong-Kong. Even from New York to faraway New Zealand the rate is now only about $1.50 per word. The cost of cabling, however, is greatly influenced by

coding,

a system by which business men use secret words for commercial messages. A cipher, on the other hand, is a system of secret letters or figures used for secrecy by Governments. Practically Governments are the only users of ciphers.Coding

has developed to an extraordinary degree of perfection. One code word will frequently stand for ten or fifteen words, and there are instances where one word has been used to represent over 100 words. Practically all commercial cablegrams are coded, and nearly all departments of commercial and industrial life nowadays have their special codes.

pp2299, 2302From his discussion of

The inevitable automatic,

this —

The increase in speed brought up another difficulty. No human operator can send so fast... To take full advantage of the speed of a modern Atlantic cable, therefore, it is necessary to have some automatic method of transmitting. The advantages of automatic transmission are higher speed, greater uniformity of signals, more legibility, and fewer mistakes.

p 2303refers to Maximilian Foster.

A successful printing telegraph.

World’s Work (August 1901) : 1195-1199

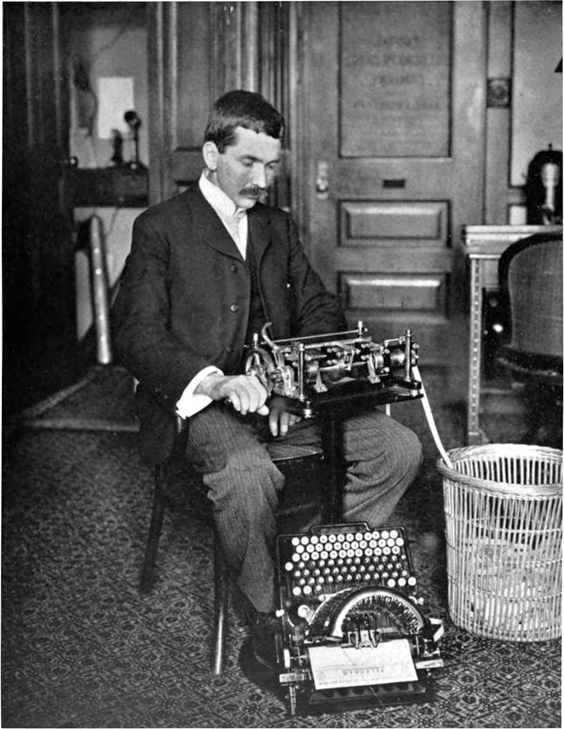

hereThis article includes photographs of the apparatus, two of them including Murray himself.

Mr. Murray and the Page-Printing Telegraph, World’s Work (August 1901) - Murray, Donald. 1905.

Setting Type by Telegraphy.

The Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers 34 (1905): 555-608

hereextracts/notes —

The simplicity of these machines and the saving of wire cost depend on the fewness and simplicity of these signals. It is in this reduction in the number and the simplification of signals that there will be found to lie not only the fundamental distinction between the telegraph and the telephone, but also the fundamental criterion of all telegraph systems...

(557); Mr Judd in discussion,but when the hideous code words...

; automatic typesetting by telegraph is discussed at 593, including obstacles; the President (at 607-08) remarks,I have never seen before that the demonstrator absolutely took the instrument to pieces before the audience and put it together again — and then worked...;

the commonality of printing telegraphy and tape-fed linotype is mentioned more than once (593) - Murray, Donald. 1911.

Practical Aspects of Printing Telegraphy.

The Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers 47 : 450-529

here

builds on hisSetting Type by Telegraph

(1905); analytical and practical. good account of press messages (463-466), newspaper private wires (466-467), evencounting words in telegrams

(473-477) - Murray, Donald. 1923. Press-the-Button Telegraphy. Second Edition. Reprinted, with alterations and additions, by permission from the Telegraph and Telephone Journal November 1914 to July 1915. London, 83pp

LC TK5541 .M8 1923

here - Murray, Donald. 1925.

Speeding up the Telegraphs: A Forecast of the New Telegraphy.

The Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers 63 (March): 245-280

Important — cannot overemphasize this — paper, that looks forward to something like the internet at least in its messaging aspect. Available alas only through paywalls.

people

text

- Edward Barron Broomhall (1848-1929)

code compiler

geneological and some biographical data, at www.springhillfarm.com/broomhall/wmbroomhall.html - William Friedman (1891-1969)

The Best Code Cracker of them All by Brad Herzog, appeared in the Cornell Alumni Magazine in March 2000.

telegraph & telecommunications history

not a good heading. revise.

- How the companies worked

being an operations-oriented section of

Distant Writing —

A History of the Telegraph Companies in Britain between 1838 and 1868

(in which year the private companies were nationalized.)This thoroughly researched and well-written resource is focused on the companies themselves. The stories yield interesting information on message practice, too. In this instance, an account of the retail operation of a telegraph office includes a discussion of the

translating

that went on within telegraph offices, in which senders’s messages were rewritten into an abbreviated telegraphic script before being passed on to the instrument, and translated back at the receiving end. (Search on the page fortranslating

but, better to read the whole, which also includes a discussion of the employment of women as clerks.This

chapter

closes with thereplacement of the (private) telegraph companies clerks and messengers by Post Office officials.

Now, one’s private messages would be exposed to the eye of the Government. And so to satisfy a new demand for secrecy in transmission, telegraphic codes began to appear on the market in quick succession, beginning with Slater’s Telegraph Code, to Ensure Secrecy in the Transmission of Telegrams (1870), Bolton’s Telegraph Code (1871), Watts’s Telegraphic Cypher (1872), and the first ABC Telegraphic Code in 1873. All of these emphasized secrecy, although in actual usage, and certainly for the ABC Telegraphic Code, economy would also be an important objective.Sadly, the creator of Distant Writing, Steven Roberts, died in 2012. The website continues to be maintained, but will not be updated.

- The Once and Future Web

Worlds Woven by the Telegraph and Internet

website to exhibition presented by The National Library of Medicine (May 24, 2001 to July 31, 2002) - The Telegrapher Web Page

research resources for the history of telegraphy and the work of women in the telegraph industry, including oral histories and reminiscences of telegraph operators; also links to digitized books on telegraphy available through the Library of America and elsewhere (e.g., Taliaferro Shaffner’s The telegraph manual (1859); and links to articles by Thomas Jepsen, who maintains this excellent site. - Morsum Magnificat

extensive information and links; newsletter soon to cease publication - The Connected Earth

website devoted to telecommunications history; telegraphy at/www.connected-earth.com/Journeys/Telecommunicationsage/Thetelegraph/thetelegraph.htm. - NADCOMM The North American Data Communications Museum

emphasis on teletype equipment, but much else besides. home at www.nadcomm.com; get overview at history page; see also good explanation of five-unit code. - Dead Media Project

Working Notes arranged by category at www.deadmedia.org/notes/index-cat.html - Transatlantic cables at Weston-super-Mare and the Commercial Cable Company

material on a specific cable station, at www.cial.org.uk. see also links on Atlantic cables The Telegraph in the Library

essay by Richard Garnett, in Essays in Librarianship and Bibliography (New York: Harper, 1899), at www.libr.org/rory/wbm14.html. provided among other material onThe Dusty Shelf

by librarian Rory Litwin. (emphasis on telautograph, rather than printing telegraph) and via Google Books here- The Western Union Technical Review provides a good window onto communications engineering during its run, from July 1947 until Autumn 1969. The link provides a table of contents of every issue, and instructions for obtaining a DVD of the entire run. Alternatively, one can download individual issues of WUTR from an MIT archive here. The Western Union alumni website is also worth a look.

- The Chappe optical telegraph system involved the use of semaphores and a code dictionary. chappe.ec-lyon.fr/ (in French) provides examples of the code vocabulary and actual messages, in addition to Les signaux réglementaires (service code) and Les (92) signaux de correspondance.

articles, theory

text

- Friedrich Kittler, The History of Communication Media

at ctheory - Steve Mullins has employed telegraphic codes, in lieu of actual cables, as evidence in a study of an Australian pearl-shelling venture in the Netherlands East Indies. See

James Clark and the Celebes Trading Co.: Making an Australian Maritime Venture in the Netherlands East Indies,

The Great Circle 24:2 (2002): 22-52, for an abstract of this work. One is reminded of other codes, generated-on-the-flyfor the present emergency,

that represent what the parties were prepared to say, rather than what they did say. - Andrew Odlyzko

has written on pricing and economic issues around telegraphy as predecessor to the Internet. see his "papers on communication networks and related topics" via www.dtc.umn.edu/~odlyzko/ - Sven Spieker

Passer l’acte: Policing (in) the Office, Notes on industry standards and the Grosze Polizeiausstellung of 1926

. (forthcoming in Klaus Mladek / Wolf Kittler, eds., Police Forces: A Cultural History of an Institution.) [ viewed 19 sep 04 ]

discusses a 3-letter police code developed in 1923 by police chief of Vienna, Dr. Brandel, but not earlier police, fingerprint and related codes dating from the 1890s and later, including a 5-letter police code introduced by NYC police commissioner Richard Enright in May 1923 at the International Police Chief’s Conference. also discusses Bertillon’sportrait parlé

anthropometric system, but not its use in telegraphic message practice as developed by R. A. Reiss.

other primary sources

text

- 1824 Histoire de la Télégraphie

Ignace Urbain Jean Chappe. Paris: chez l’Auteur, 1824

transcription of Table of Contents

two scans are accessible, from Michigan and the Bodleian, respectively :

scan 1 : Michigan copy

Histoire de la Télégraphie

This copy contains the plates, which are not always found bound with the text. Naturally, the scans do not capture the line detail of the original. There is no index to the plates, which are referred to in the body of the text.scan 2 : Bodleian copy

Histoire de la Télégraphie

This scan misses page 262; this copy excludes the 34 plates. - 1863 A Handbook of Practical Telegraphy

Published with the sanction of the Chairman and Directors of the Electric and International Telegraph Company. Illustrated with Numerous Diagrams.Robert Spelman Culley. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green. 1863

original at BodleianPreface (vii); Introduction (1); Part 1, Sources of electricity (batteries) (4); Part 2, Magnetism, and the connection between magnetism and electricity (26); Part 3, Resistance and the laws of the current (43); The earth as part of a circuit (54); Part 4, Insulation (59); Part 5, Induction (83); Atmospheric electricity (93); Earth currents or deflections (94); Part 6, Testing for insulation or resistance (96); Part 7, Faults, and the methods of discovering them (103); Part 8, Signal apparatus:— Switches, commutators, or turnplates (126); Printing telegraphs (130); Cooke and Wheatstone’s needle telegraph (146); Part 9, Construction of a line (155); Part 10, The strain and dip of suspended wires (168); Appendix and notes (173); Index (189).

-

Visible Speech Telegraphy

in

Alexander Melville Bell. Visible Speech : The Science of Universal Alphabetics; or Self-Interpreting Physiological Letters, for the Writing of All Languages in One Alphabet, illustrated by Tables, Diagrams, and Examples.

London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co, 1867

original at Bodleian

pp 101-103 - 1903

Signaux Télégraphiques

Signaux Télégraphiques adaptés au nouveau langage convenue, classification des signes, etc.

James Nicolson

original at Michigan; hereProposes a novel system of consonant-vowel pair code-words, each letter-pair given a single Morse-like elementary signal set. Nicolson writes, in 1897:

Uncommon words, or words not generally employed in ordinary parlance, are, for evident reasons, generally used in the formation of telegraphic codes. Our codes provide this requisite, and combined with two alternate series of signals, of odd and even numbers of elementary motions, will prove more intelligible to the telegraph operator than promiscuous signals of from one to five motions, representing the letters of the Official Vocabulary, the words of which are, for the most part, unintelligible to him.

author of —

Telegraphic Signals and International Code Vocabularies, with a suggested reclassification of conventional telegraph signals, etc.

(1897)Telegraphic Vocabularies adapted to Telegraphic Signals.

Whittaker & Co.: London and New York; Robert Grant & Co.: Buenos Aires [printed], 1902-1903Nicolson’s Consono-Vowel Vocabulary for Telegrams in Preconcerted Language. I.— Part I.

(1904)It will be apparent that this System, far from interfering with the phraseology of existing code books, will afford an important economy in the transmission of the same.

000000 EBEBEBEN

000001 EBEBEBOP

000002 EBEBEBUV

000003 EBEBECEP

000004 EBEBECOV >

004196 ECELUPEZ

004197 ECELUPOB

004198 ECELUPUC

004199 ECELUVEBNicolson’s Consono-Vowel Condensor C. for Telegrams in Preconcerted Language (1904)

- Signals and Instructions

Signals and Instructions, 1776-1794: with addenda to vol. xxiv

Julian S. Corbett, ed. Navy Records Society, 1908