telegraphic codes and message practice

scanned code directory

Codes of William Shepard Wetmore, 1873 – 1880

draft

| 1873 | Commercial telegraphic code | 352pp Shanghae, Da Costa & Co. |

LC HE7676 .E546 |

| 1875 | General Commercial Telegraphic Code | 565pp Shanghae. Tung-Hing Printer, Honan Road, C. No. 76. |

BL 8244.e.29 /

google LC HE7676 .W56 |

| 1876 | Supplement to Commercial Telegraphic Code | 44pp Shanghae : Tung Hing |

BL 8756.df.1. |

| 1880 | Commercial telegraphic code | 656pp London, S. Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington |

LC HE7676 .W55 |

William Shepard Wetmore, 1827-1898/1900?

The compiler of this code is not William Shepard Wetmore (1801-62), a New Englander who made a first fortune in the South American trade, and a second one in the China trade, from his base in Canton 1833-39. See his wikipedia page and, above all, Walter Barrett's The Old Merchants of New York City (1863), particularly pp 298-299, where we learn that "His firm in Canton and Shanghai, is still kept up as Wetmore, Cryder & Co. the partners are W. S. Wetmore (same name as his own, but a nephew,) and Mr. Wetmore Cryder, who is yet living, though retired from business, and managing the estate of his late brother-in-law".

Our W. S. Wetmore is evidently the New York University graduate of 1847 (A.M. 1852), born Feb 26, 1827, described (in 1884) as living in Shanghai, and "Formerly Consular Agent of the United States." William Shepard Wetmore, same date of birth (at S. Albans, Vermont) was in the Harvard Law School class of 1849, and died at Brighton, England either in August 1898 (on p 303) or 21 July 1900 (p465), both pages in the same volume of the Harvard Graduates' Magazine 9 (1900-1901).

Some further sense of his life and interests — I have located no obituary or memorial — is suggested by publications other than his codes —

- William Shepard Wetmore. An improved mode of protecting troops under fire. British patent number: 2860 published: 31 October 1870

listed at AbeBooks by M. A. Stroh, here (viewed 7 July 2017) - William Shepard Wetmore. U.S. Patent No. 122,206, Improvement in Spade Bayonets. 1871

- Artificial defences for troops in the field.

Shanghai, Printed by Da Costa, 1873.

28 p.

LC YA 19096 YA Pam - W. S. Wetmore. Letters on the Gold-silver Question from the China Stand-point.

Shanghai : Printed at the "North-China Herald" Office. 1893

scan of Harvard copy at Google Books - W. S. Wetmore. Recollections of Life in the Far East.

Shanghai : Printed at the "North-China Herald" Office. 1894

(regarding events in the 1850s)

scan of Harvard copy at Google Books - W. S. Wetmore. Why gold prices continue to decline.

Shanghai, Printed at the "North-China herald" office, 1895.

2 p.l., 10 p. 22 cm.

LC HG562 .W54 - "A Protest," by W. S. Wetmore, President of The Eastern Bimetallic League (established 1894), in a volume containing several items, including these by Wetmore : "Gold monometallism and its effects upon wages" (December 1894), "Monometallism perplexities" (January 1895), and "Why gold prices continue to decline" (March 1895) (all listed here)

Wetmore is also the subject of numerous letters from the Legation of the United States in Peking, ca 1882-83, regarding a project to establish a cotton-yarn factory in China, and the Chinese Government's refusal to grant permission for it, having previously granted a monopoly for the same to another (Chinese) company. 129-197 passim (search "wetmore") in the volume Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States (1884)

aside —

I confess that my interest in identifying this William S. Wetmore was whetted, at least in part, by accounts of the elder Wetmore's second marriage, that ended owing to an "indiscretion" of his rather younger wife Anstiss Derby Rogers (1822-1889) with her husband's coachman. See the account in Barrett's The Old Merchants here. See also the stunning sculpture of Anstiss by Hiram Powers (1805-73), in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution, including the short account of that sculpture's fate, on the same page. Our code-compiling Wetmore was of another line in that family.

I turn now to the General Commercial Telegraphic Code (1875), whose scan became available in December 2016 and which is the only one of Wetmore's codes that I have seen (and seen only as a scan, albeit a printed and bound one).

| 1875 | General Commercial Telegraphic Code. By W. S. Wetmore. Author of The Commercial Telegraphic Code.. | Shanghae. Tung-Hing Printer, Honan Road, C. No. 76. | BL 8244.e.29 /

google LC HE7676 .W56 |

English (and English sounding derivative) codewords. 565pp.

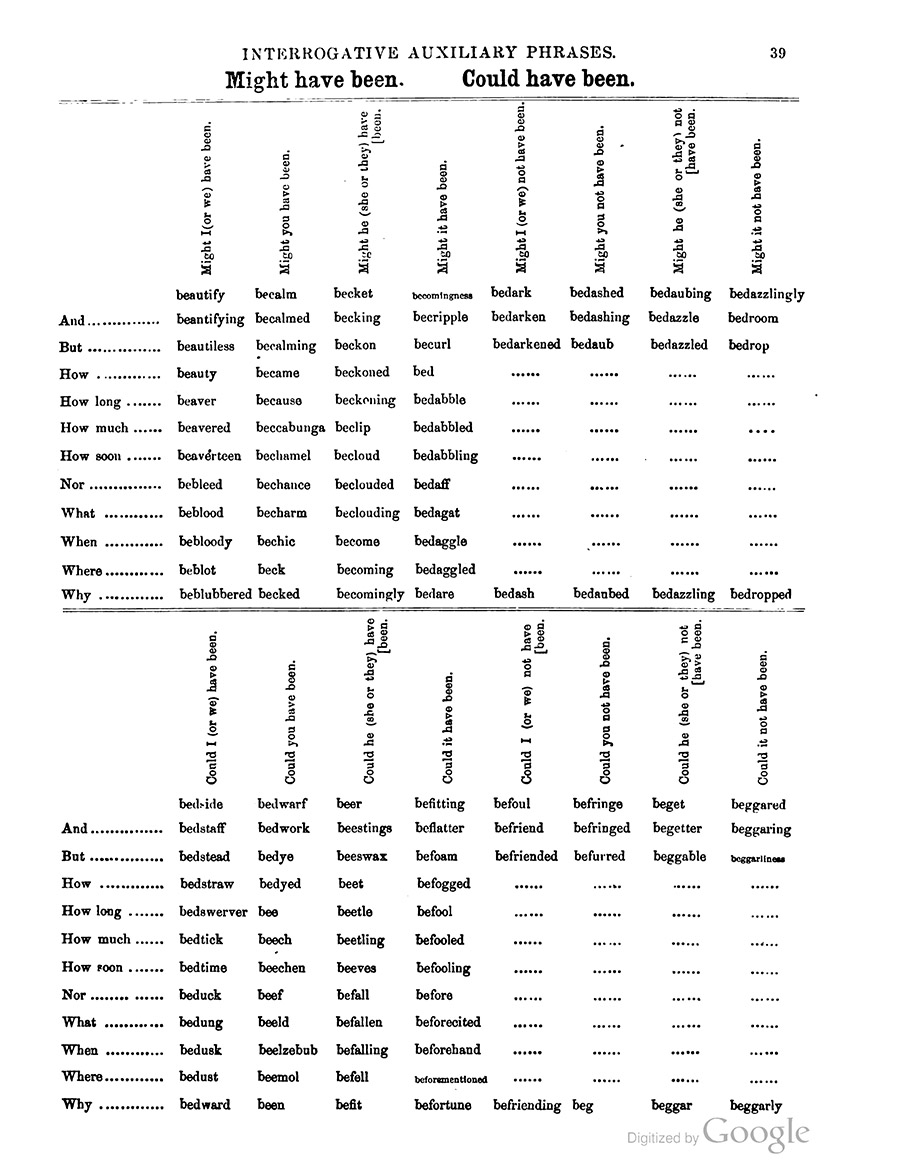

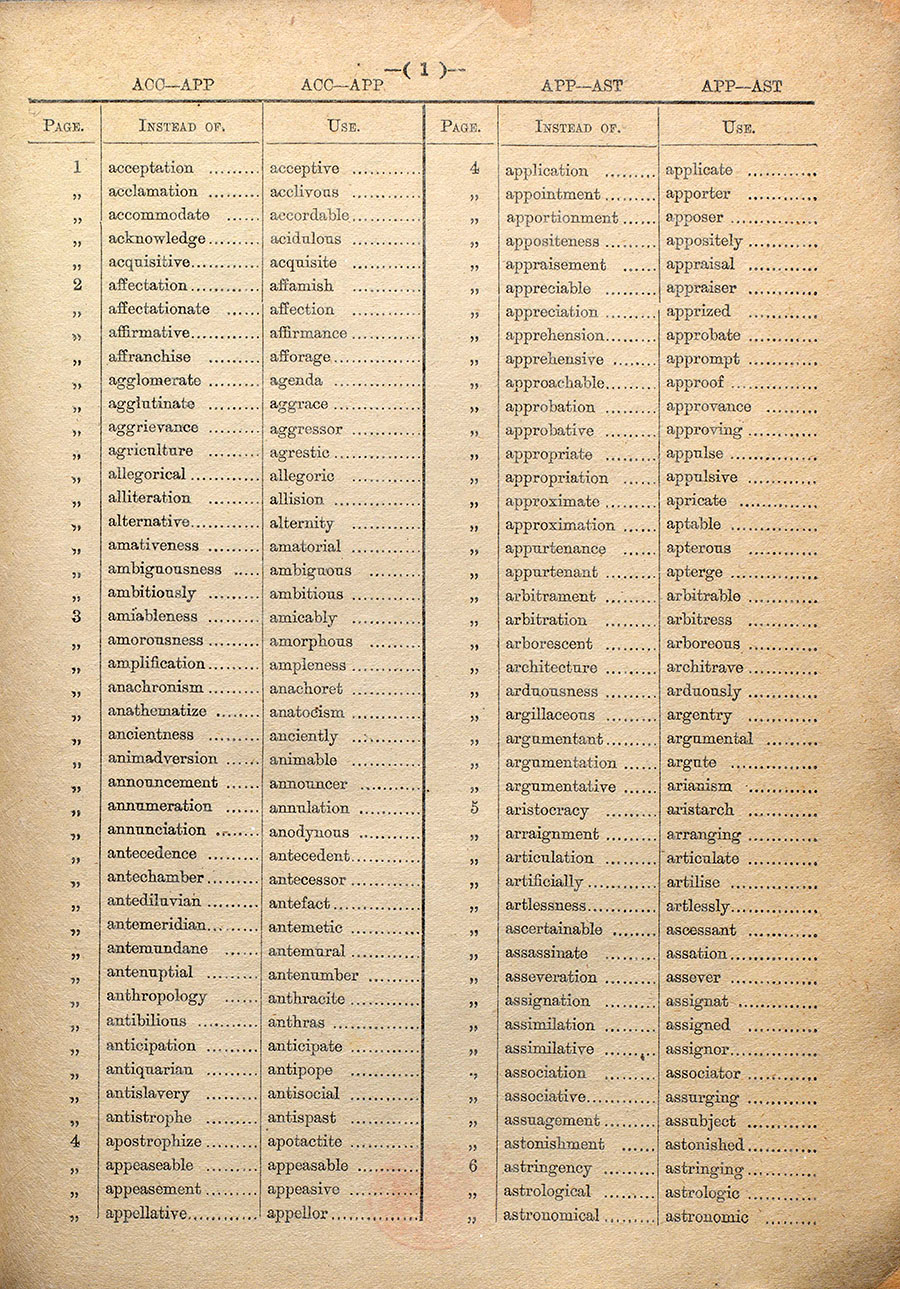

Interrogative auxiliary phrases, pages 1-10, 11-30

Auxiliary phrases, pages 31-40, 41-60

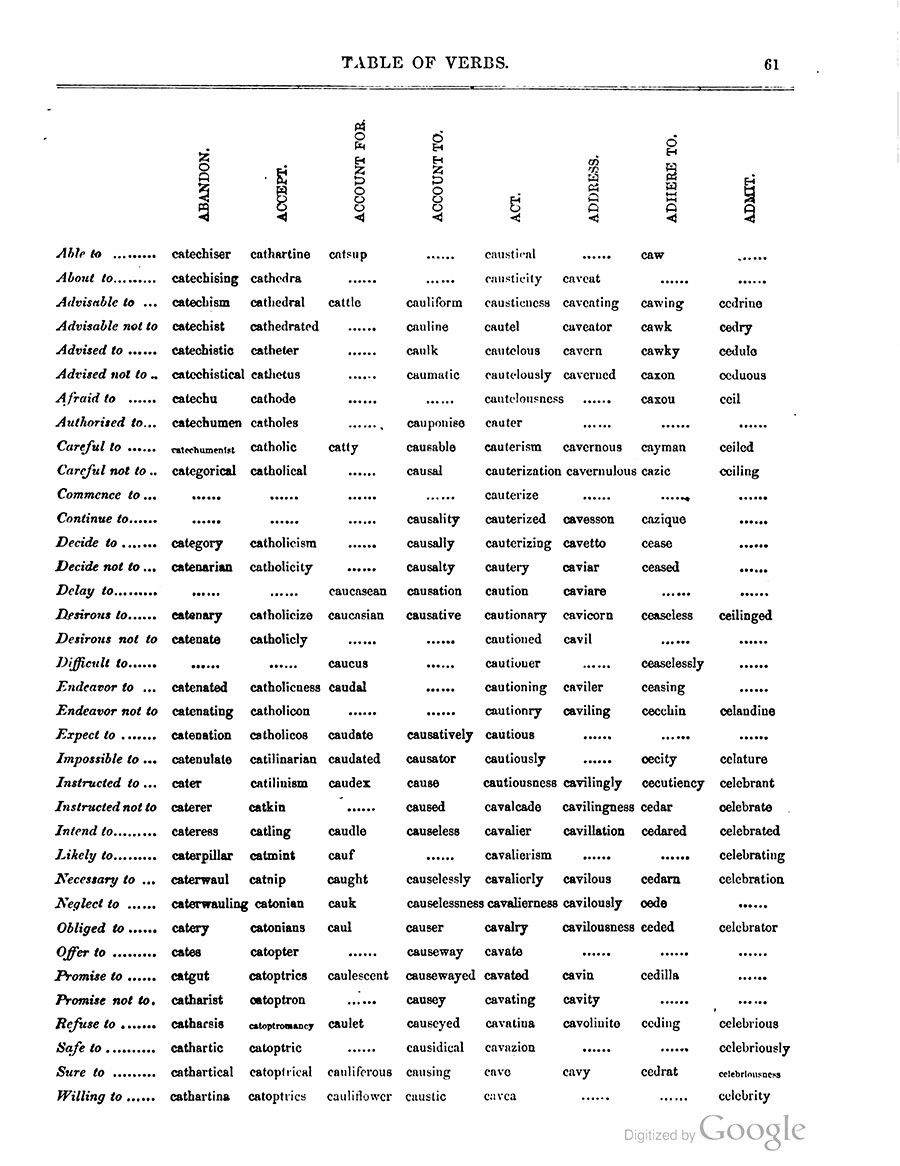

Table of verbs, pages 61-87

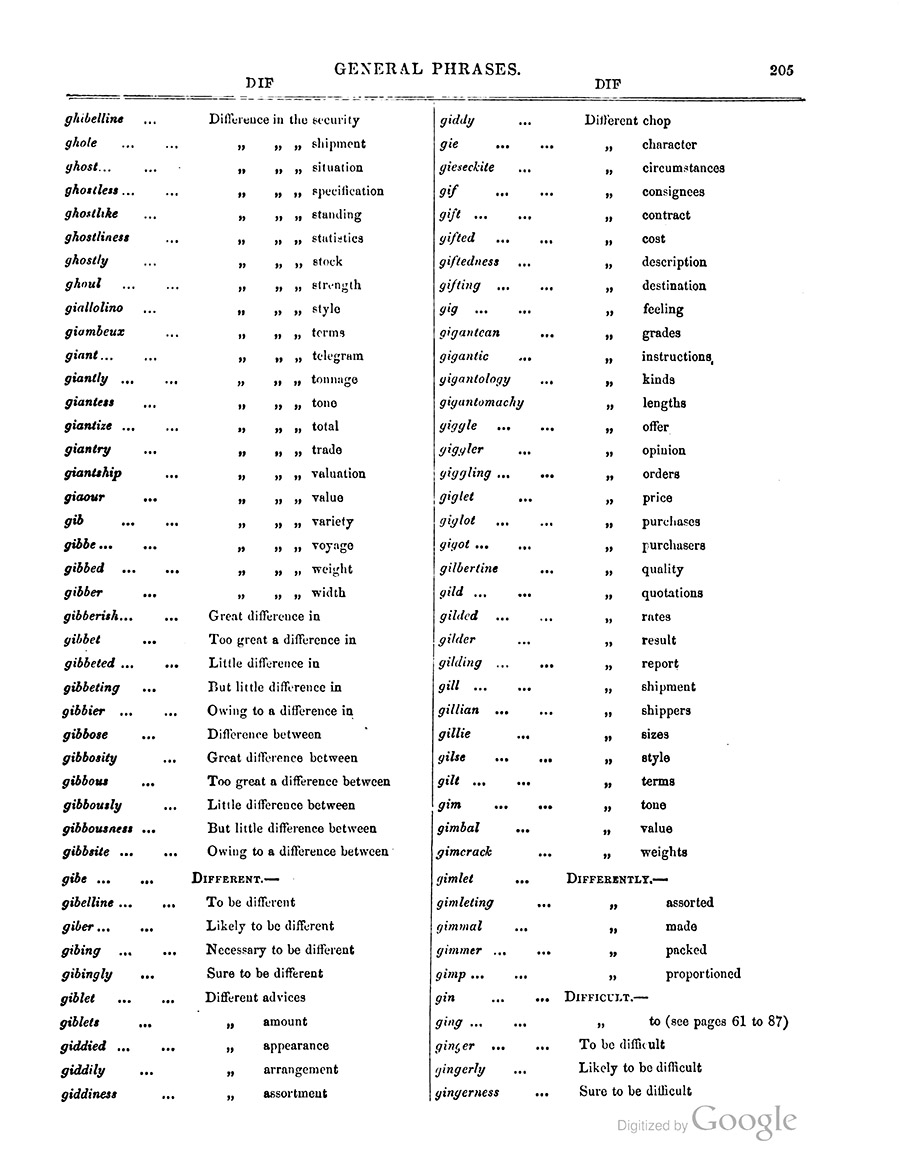

General phrases, pages 88-565

Wetmore's General Commercial code can be used as a stand-alone, quasi-"verbatim" code but, as he explains in his preface, "it is as an auxiliary that it is believed it will be found especially useful." That is, it should be used with specialized or private codes, whose phrases and tables would be more attuned to specifics of, for example, the cotton or tea trade. He adds that it can accompany his "Commercial" code (of 1873), and a second edition (that would appear in 1880).

The codewords are English dictionary, or English-sounding, words, some as short as three letters (e.g., bee), some as long as 14 (e.g., beneficialness) or 16 letters (ambidextrousness); their differentiations are marginal in many cases, e.g., boxed, boxen, boxer. In his preface, Wetmore acknowledges that "in an extensive code like the present where a very large number of indicators is required," some codewords will differ from others by only a single letter. He concludes by suggesting that if care is taken in both writing a message for transmission, and receiving it, errors will be no greater with his indicators, than with others (more carefully selected or invented).

I sense that Wetmore compiled these codes on the basis of experience in handling telegrams, both in New York and China, and suppose that he referred to private or other (published) codes whilst compiling them.

Tables and phrase matter do not go deeply into any specific matter: nothing under the headings cotton or silk, for example, or even tea. However, there is some local (Chinese) color, e.g., phrases under the head "chop" —

especial / Chop.

especially / Chop mark

especialness / Chop name

esperance / Chop of silk

espial / Chop of tea

espied / A bad chop

espier / A common chop

espinel / A crack chop

espionage / A fair chop

esplanade / A well known chop

espousal / By the chop

espousals / Per chop

espouse / The whole chop

The first sections of the code, through page 87, consists of tables, one of which is shown below.

|

|

| page 39, W. S. Wetmore, General Commercial Telegraphic Code (1875) | |

A speciment page of "general phrases" is shown below. Other code compilers might not use adjectives as phrase heads, but the topic being described. Not "different chop" but, under the head "chop," "different chop."

|

|

| page 205, W. S. Wetmore, General Commercial Telegraphic Code (1875) | |

A "see pages 61-87" note is inserted for ging — verbal constructions with the word "difficult." The first of those pages, in the Table of Verbs, is shown below.

|

|

| page 61, W. S. Wetmore, General Commercial Telegraphic Code (1875) | |

Well suited to multiple-faceted matters like price, quality and volume (e.g., in a cotton or other commodities code), tables are also employed in so-called "verbatim" codes. Such codes strive to approximate natural sentence constructions (subject, verb, object), and provide a variety of modal auxiliaries with which to qualify verbs.

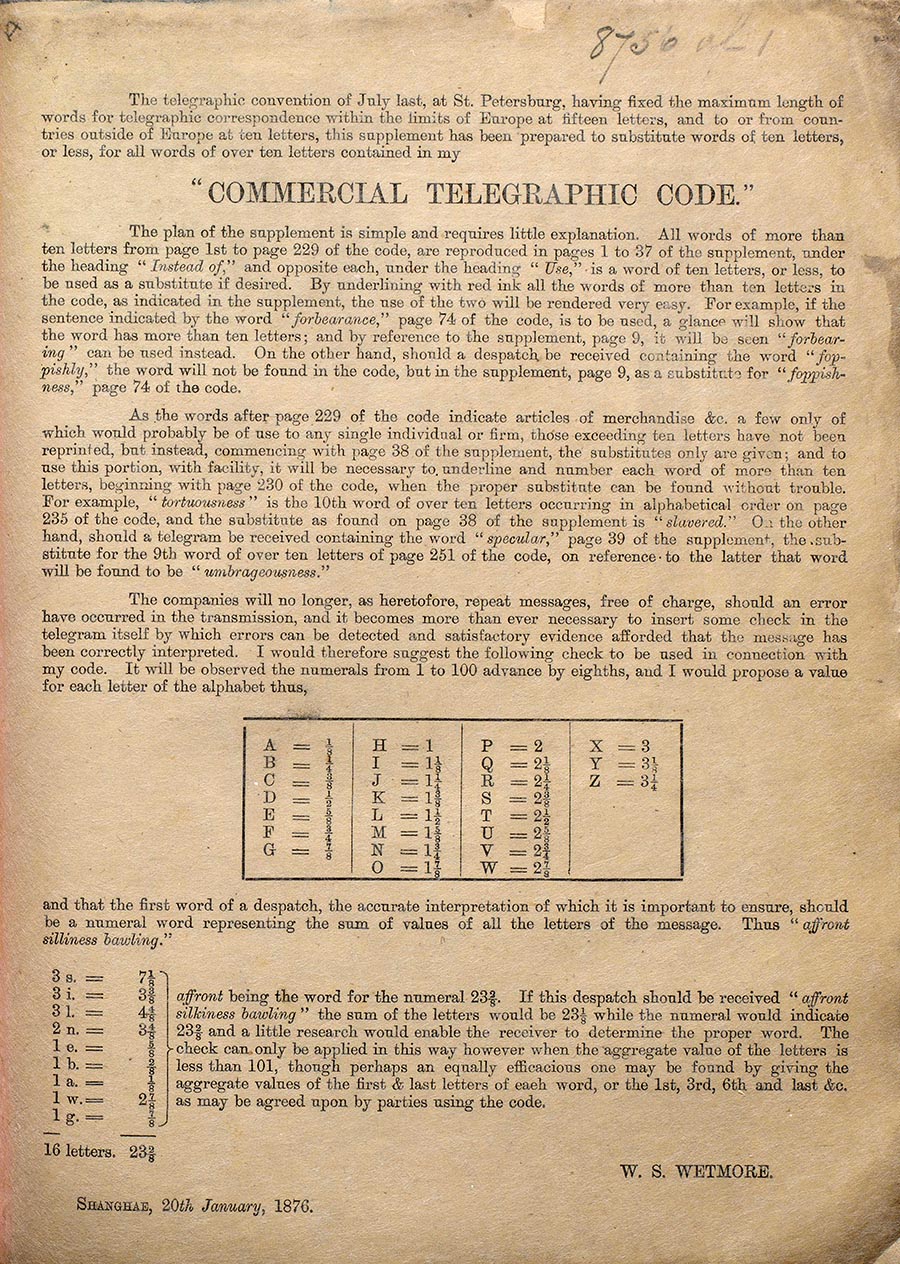

| 1876 | Supplement to Commercial Telegraphic Code. | Shanghae, January, 1876. Tung-Hing Printer. | BL 8756.df.1. |

44 p. ; 8º.

Provides substitute codewords for any codeword in the Commercial Telegraphic Code of 1873, of more than ten letters. None of the substitute words (of ten or fewer letters) appears in the 1873 code. The expectation is that the user would underline (in red) all words of more than ten letters, and refer to the supplement for the shorter replacement. The switch was necessitated by the telegraphic convention at St. Petersburg in 1875, which "fixed the maximum length of words for telegraphic correspondence within the limits of Europe at fifteen letters, and to or from countries outside of Europe at ten letters." (p iii).

The St. Petersburg ruling on length of codewords, and other similar rulings in subsequent years (1908, 1932) would occasion revisions and re-editionings of existing cable codes that would otherwise have become unusable (and unsaleable). Wetmore's investment in his Commercial Telegraphic Code of 1873 needed to be protected; I assume — without having seen it — that his last (1880) code incorporates admissable codewords of ten letters or fewer.

The Supplement also provides a check system, where every letter is given a number, whose sum would also be indicated by a codeword to be appended to the message. The system only works where the "aggregate value of the letters is less than 101," but the author suggests means by which this limitation can be gotten round.

|

|

| preface, W. S. Wetmore, Supplement to Commercial Telegraphic Code (1876) (c)British Library Board (slightly cropped to square; levels 100 1.00 240; used with permission) |

|

The check system, whose letter values advance by eighths, is ingenious if more complicated than similar systems advancing by whole numbers.

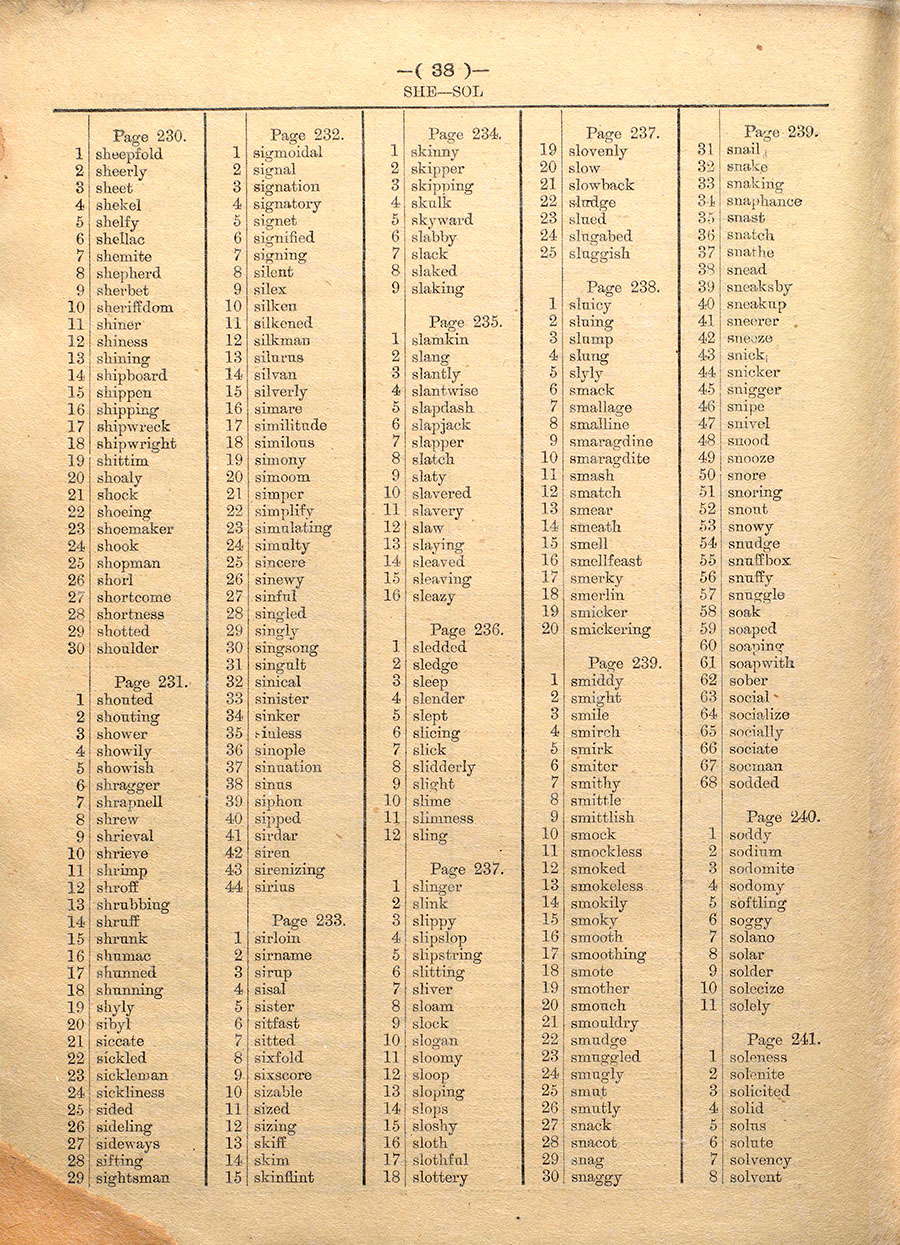

The Supplement is divided into two sections, the first listing the deprecated codewords and their replacements (pp1-37); the second listing only the replacements and the page numbers on which their respective deprecated codewords are to be found (pp 38-44). The rationale for the abbreviated treatment in the second section, is that these codewords "indicate articles of merchandise &c. a few only of which would probably be of use to any single individual or firm," so that users need mark up only pertinent pages in their 1873 code.

|

|

| p1, W. S. Wetmore, Supplement to Commercial Telegraphic Code (1876) (c)British Library Board (slightly cropped to square; levels 100 1.00 240; used with permission) |

|

|

|

| p37, W. S. Wetmore, Supplement to Commercial Telegraphic Code (1876) (c)British Library Board (slightly cropped to square; levels 100 1.00 240; used with permission) |

|