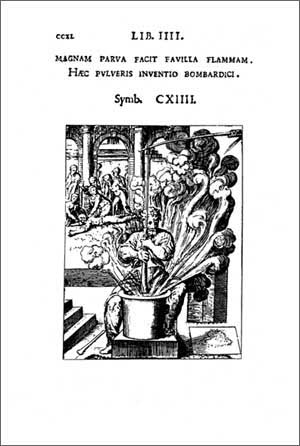

Emblem CXIIII, in Achille Bocchi (1488-1562), Symbolicarum Quaestionum de Universo Genere (Bologna, 1574). From the Garland reprint of that edition, with introductory notes by Stephen Orgel, 1979. The book first appeared in 1555.

Magnam parva facit favilla flammam.

Haec pulveris inventio bombardici.

From a small spark, a great flame is created.

Thus was destroyed the inventor of gunpowder.

The emblem illustrates the invention of gunpowder by the accidental ignition of a mixture of sulphur, saltpeter and carbon. The alchemist (whose prone body is seen in the upper left) dies in the discovery. The idea is that a small spark, created from the combination of several elements, can ignite meaning. Those elements might well include the image, motto and poem of an emblem.

See the discussion of this emblem in Elizabeth See Watson. Achille Bocchi and the Emblem Book as Symbolic Form (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge UP, 1993)

Emblems were a genre that deployed word and image for rhetorical, ethical and/or educational purpose. They exhibited an economy of expression, typically in the three-part form of motto, allegorical image and explication, that served to contain their baroque piling-on of detail in a tight, formalist forcefield.

Emblems came into being as a genre with the publication, in 1531, of Emblematum Liber, authored by Andreas Alciatus. That crudely illustrated book was a plagiarization of a collection of epigrams published by Alciatus in 1522, but the new form was successful, and over 150 editions of Alciati's collection, alone, appeared over the next century. Something like 2000 emblem books were published in the heyday of the genre. They were typically used as visual dictionaries, or sourcebooks, by artists and others (the most famous in this regard was probably Cesare Ripa's Iconologia (1593)), but were also used in education. Projecting back, they were a cross between encyclopædia and photo stock book.

Emblems are open, not closed. The cut-up, paste-up, juxtapositional nature of the emblematic mode lends itself to new occasions of inquiry and meaning.

Hence the emblem form (if not tradition) remains alive in our day, both implicitly in advertising, and more or less explicitly in works by artists as diverse as Ian Hamilton Finlay and the late David Wojnarowicz.

It is sometimes suggested that emblems "influenced" advertising. It is the case that print ads tend to be armatured around three nodes -- a picture, some copy, and a logotype that glues it all together. It is also the case that the pictures have tended to become more complex, while the copy has become simplified. But to argue that advertising is a phase of an emblematic tradition doesn't really aid in understanding either advertising or emblems.

The key article here is Peter M. Daly, "Modern Advertising and the Renaissance Emblem," although Daly argues only that advertising "relies on symbolism and on techniques of verbal and visual communication that are strikingly reminiscent of the emblem."

Advertising does not ordinarily open the seams of its flawless and perfect surface to encourage meditation on moral or ethical questions. Its ends are immediate, not delayed. Yet exceptions to the rule exist. Benneton, in its print ads and in its journal Colors does provide elements whose juxtapositions are grist for moral reflection. In the magazine especially, images are accompanied by essays (the explication?) and by captions (the motto?).

Peter M. Daly, "Modern Advertising and the Renaissance Emblem: Modes of Verbal and Visual Persuasion," in Karl Josef Holtgen, Peter M. Daly and Wolfgang Lottes, eds., Words and Visual Imagination: Studies in the Interaction of English Literature and the Visual Arts [Erlanger Forschungen Reihe A, Geisteswissenshaften Band 43] 1988: 349-371

6 july 02