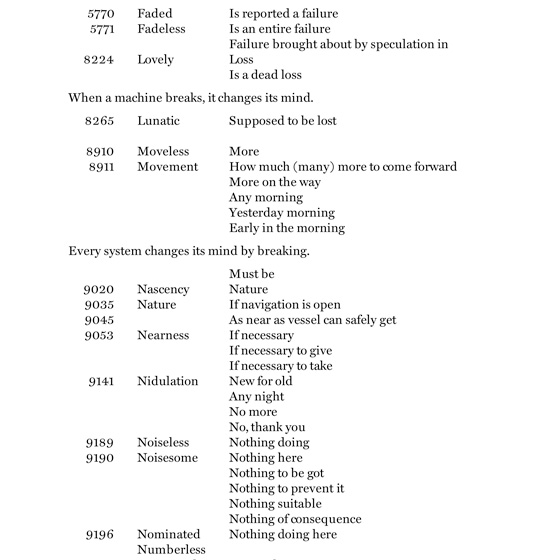

Japan 11 May 2011

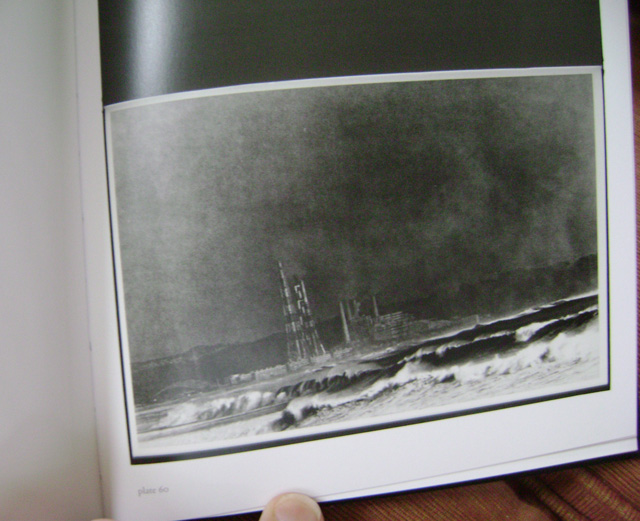

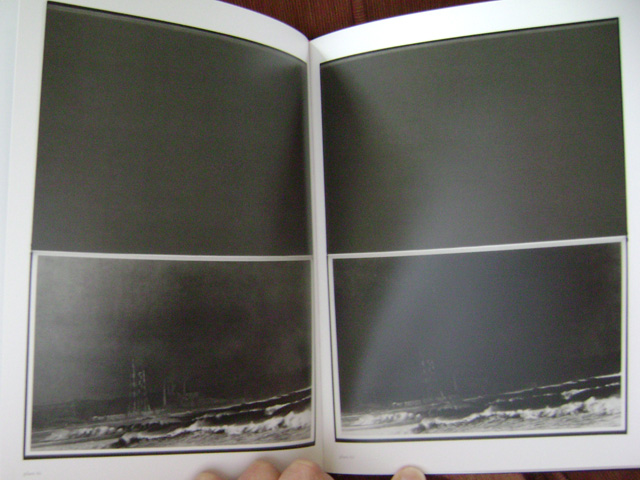

one of group of five images of power plant, concluding volume one of Takanashi Yutaka’s Toshi-e

(1974, republished 2010).

Lots of thinking about Japan of late — the earthquakes, tsunami and nuclear disasters; also, photographs, memories, a film screening. I lived and worked in Tokyo 1982-88.

It’s the movie, Linda Hoaglund’s AMPO: Art X War

about the U.S.-Japan Mutual Security Treaty, that instigated this writing. But the photographs and memories run deeper. This is a long and impressionistic post; here are the parts:

Takanashi Yutaka’s Toshi-e

blindness and prescience

ANPO : Art X War

dignity

飢餓海峡 (Kigakaikyo), 1965

A stunning new edition of photographer Takanashi Yutaka his Toshi-e (Towards the City) (Errata Editions, 2010) arrived a few weeks ago. For sample pages, see errata editions’s Books on Books #6. I first saw Takanashi’s work at Inax Gallery in Kyobashi in June 1988. Its cool

must have appealed to me, something akin to the industrial park photographs of Lewis Baltz, and I bought several of Takanashi’s books around that time. The earlier work has been brought out again by Errata Editions. Here’s their description: Toshi-e was a two-volume set of books from one of the founders of the avant-garde Japanese magazine Provoke. Published in 1974 and considered the most luxurious of all of the Provoke era publications, its brooding, pessimistic tone describes the state of contemporary life in an unnamed city in Japan undergoing economic and industrial change.

The two books were Toshi-e and Notes Tokyo-jin. The first is mainly buildings, margins, infrastructure. Some hillsides, some not-yet developed areas around the edges of the city. Many shots around Shinjuku (e.g., a line of railway tank cars, shoppers, pedestrians); sides of buildings, roads. The second feels more populated: shoppers, commuters, people out on the street, in cars, on park benches, at sports events, a betting parlor. Apartment complexes, students lining up for university exams, a housing exhibition. An anti (Vietnam) war demonstration.

Plate 108, in Toshi-E (Notes Tokyo-Jin), (1974, republished 2010). Shinjuku Station, West Entrance Square (workers taking a break)

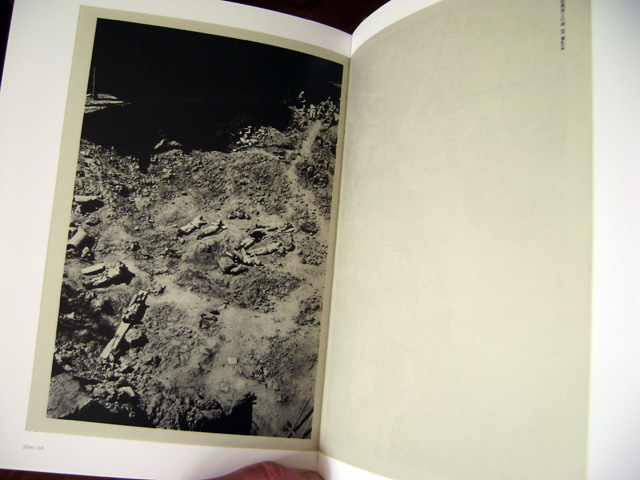

I wonder what’s in that dirt, what’s in the pile of rocks and bubble at bottom and at edge of upper shadow.

The images in Toshi-e might be said to clear a space — make a clearing — for thinking, as the growing city asserts a space for itself which, necessarily, involves displacing, relocating edges, burying. This volume ends with a haunting image, repeated five times in successively darker views, of a powerplant at the edge of the ocean, off to the left behind approaching waves whose froth is the main and ultimately sole repository of light. These two books at once document and participate in their own time. Takanashi was an outsider, but also an insider as a professional photographer.

Notes Tokyo-jin is printed on a different stock; facing each plate is number, location and occasional brief notes. There’s perhaps a little more particularity to it. This volume is more about filling/populating that space, living in it.

In both volumes, no one photograph is more important than another. Some are visually busier than others. Sequencing is all important. A few images appear more than once, either in the same volume, or in both. These include a child peering into a doll house display at Isetan in Shinjuku (Tammy-chan ¥1,000, Pepper-chan ¥700

) —

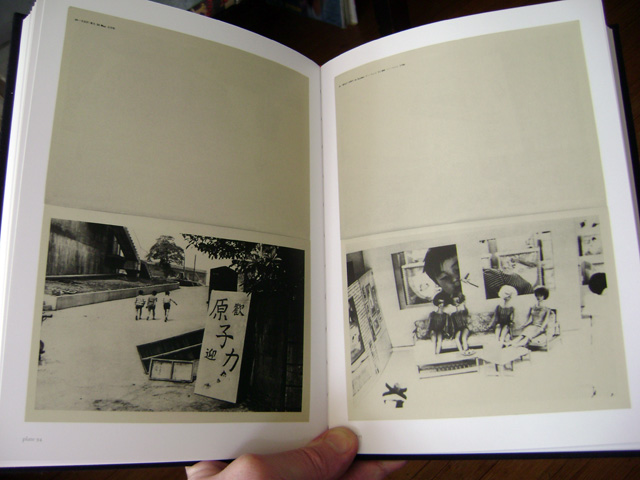

Plates 94 and 95, in Toshi-E (Notes Tokyo-Jin), (1974, republished 2010). Image at left at Tokyu University, sign says: Welcome Nuclear Power!; image at right is of a Tammy and Pepper doll display, at Isetan Department Store in Shinjuku.

The plate that immediately precedes the second appearance of the doll house shows three boys walking up a driveway, apparently at Tokyo University where construction is underway. A sign at the side of the road says Welcome Nuclear Power,

over Tezuka Osamu’s Atom

(Astro Boy)).

Other images: a fellow eating in Shinjuku; a house located next to a Shinjuku underpass; fashion models and/or women in space-age looking clothes (dressed for work at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics?)

Rather than me overextending and getting nowhere, read Gerry Badger’s fine essay in the Errata book, Image of the City – Yutaka Takanashi’s Toshi-e.

For some contextualizing, read the first part of Masashi Kohara’s A Portrait of Takuma Nakahira.

(Nakahira had been a founder of the magazine Provoke, whose other members included — in addition to Takanashi — Moriyama Daido, the critic Koji Taki, the poet Takahiko Okada.) His For a Language to Come (1970) although later disavowed (in a kind of retraction) was revived in 2010.

These and later (color) photographs by Takanashi remind me of my own wanderings in Tokyo, Saturdays or Sundays when I’d set out on long walks with a compact canvas bag, containing maps, camera, film. Maybe swimsuit and goggles, if I were going to stop first at Takadanobaba for a swim in their two (only) lanes designated for laps. Where to go? Toyosu. Artificial Yume no shima (夢の島公園 (here, Dream Island Park), where I saw the Daigo Fukuryu Maru). Kawasaki. Akabane to Kawaguchi (favored by Takanashi in later books). Chiba. Out from Ikebukuro. Asakusa and beyond. Nippori and beyond. Etceterae many. Look at a map, determine an area I’d never been, go to a station there and set out, knowing that late in the afternoon I’d find some way back. I covered a lot of ground in those years, 1982-88. These were something like my own pilgrimage with 88 temple stops, just minus the temples, and not in Shikoku. Pointless walks, some of them, in boring warehouse deserts in the flats, liquefaction zones buried under asphalt. Time that might have been put to better use.

blindness and prescience

Here’s Kohara on Nakahira and others in that group.

Their characteristic grainy, blurry, shaky pictures are the photographic expression of their doubt about a photography that amounts to illustrating a self-enclosed aesthetics or language. They are a conclusive reflection of a time whose contours are slowly dissolving. They are attempts not to

shoot

the pictures actively, but rather to allow the pictures to develop on the basis of a deliberately passive stance, with the frequent use of wide-angle lenses and no-finder technique....

Takanashi’s work wasn’t so grainy, nothing like Nakahira’s anti-photographs, but it was open to what was out there, and it was fast-looking, rough, inclusive. The style of the Provoke group is known as are, bure, boke (grainy, blurry and unfocussed); I take it to be an aesthetic practice in which a learned kind of blindness is not handicap but advantage. The blind photographer might employ other rules, other inputs in deploying his/her camera. A photography that is in some sense blind,

because untutored, careless, may give it a special power to see what eyes might not catch.

The most obvious instance of this prescient photography — at this moment — is the group of five images of the power plant that close the first book. But there are others, e.g., the doll house display, following directly on the Nuclear Power Welcome

sign. But the actions in all of these scenes, the human activity shown, is part of a compact — a deal — made by the people in any city, to construct the systems in which their lives can take place. Takanashi presents evidence of the lived activity, and the displacement it entails.

Plates 61 and 62, near end of Takanashi Yutaka his Toshi-e

(1974, republished 2010).

Japan in the 60s and 70s was about hard work, sacrifice. The hard work didn’t diminish in the 1980s, but was joined by high-quality consumption. I mean here connoisseurship: attention to detail, craft, design, quality, brand, sophistication. Beneath it all, energy (electrical whether fossil fuel or nuclear derived); huge infrastructural projects (water projects, filling in of the Tokyo Bay); export of manufacturing function; shrivelling up of agriculture; the U.S. defense umbrella.

an aside —

around 3:07/5:41, Japanese schoolboy of Kofu in 1963. Prayers, silkworms, bathing

Japanese farmers are very hard working people. Taro thinks he will not be a farmer.

So says the narrator, while showing scenes of hard work in the rice fields. The movie then cuts to Tokyo and images of what Taro might choose to become — a scientist, teacher, doctor, engineer, shipbuilder (or perhaps a textiles engineer for a petrochemicals company, developing new artificial fibers!). From a video uploaded to YouTube on 11 May 2011 by Michael Rogge, Japanese schoolboy of Kofu in 1963. Prayers, silkworms, bathing. The film starts with stop at the temple, on the way home from school. Once home, Taro helps his family lay mulberry branches out for the silkworms. Later, we switch to the rice fields, to which Taro carries tea to his laboring family.

around 3:10/5:41, Japanese schoolchildren in 1963 Kofu

Interesting comments at that YouTube page, about how Kofu is now a town of old people. Strange to see the house, the silkworms upstairs, the local landscape, ofuro with his father (or older brother?) at the end of the day, and to know that Taro and others would leave it all behind.

The same boy appears in Japanese schoolchildren in 1963 Kofu, also uploaded by Michael Rogge (on 10 May 2011). Calligraphy, abacus (soroban), children clean the school building, sweep the dirt outside. Taro arrives home a little late, to eat dinner with his family (television on in the background: brings to mind the Three C’s

that were requisite in the mid-1960s — car, color television, cooler (air conditioner), replacing the b&w television, washing machine and refrigerator of the 1950s). Taro then retires with his brother. The narrator explains the tatami, and says Japanese people do not like too much furniture. They prefer to have only space.

Next day, a school trip to the mountains, beautiful stream. It is most beautiful to be a child, it is like the springtime...

As the movie goes from child to child, eating their lunches, the camera focuses on Taroko, who is described as a very shy girl, but it is good for Japanese girls to be shy.

Attempt to post this concluding comment at YouTube page failed, and so here it is:

I would love to know Taro’s subsequent story. He’s 58, maybe 60 now. Did he leave for Tokyo and one of the professions sketched out for him? Did he remain in Kofu? What of his own children (and perhaps, by now, grandchildren)? What does he think now, about his life, about this movie in retrospect?

And about these films: Who made them, and for whom? They somehow predict a future that perhaps has gone as planned, but also brought about some outcomes that could not have been foreseen.

ANPO : Art X War

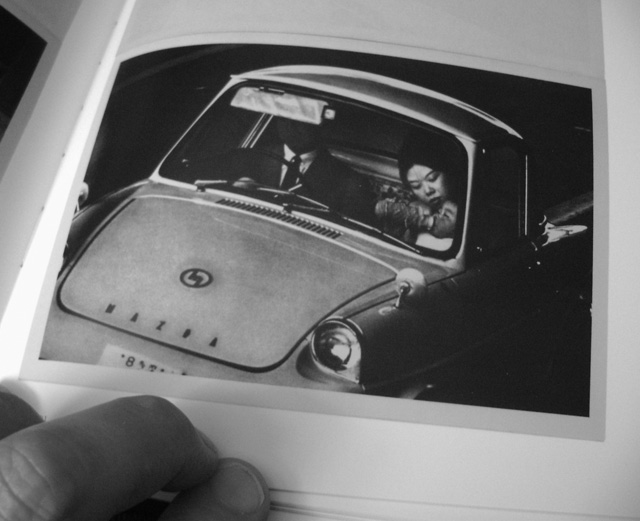

One of Takanashi’s photographs appears in Linda Hoaglund’s ANPO: Art X War

(2010). A (nuclear) family in a tiny Mazda R360 Coupe. The husband drives in suit and tie; passenger wife feeds infant from a bottle. They’re going somewhere.

Suginami-ku: Tokyo Beltway 7

in Notes Tokyo-Jin, part 2 of Toshi-e

(1974, republished 2010).

Cramped maybe, but the photograph is kinetic and forward-looking. There’s no look in the rear-view mirror here, no concern with anything but getting somewhere. That’s a story that is not really present in ANPO,

which I saw at Harvard’s Carpenter Center, April 11. I think the film is confused — blinded by its own political agenda — but would recommend it nonetheless to anyone interested in modern Japan. Here’s the film’s own about:

In 1951, Japan signed the US-Japan Mutual Security treaty (ANPO in Japanese), giving the US the right to maintain armed forces on their soil. A growing resistance to the U.S. military presence culminated in the protests of 1960 — in which millions of citizens took to the streets.

ANPO: Art X War

allows the art of Japanese artists to guide viewers through the opposition to the effects of the government response and the onerous U.S. military presence that has disrupted Japanese life for decades.

Ryan Holmberg provides a good summary and critique of the film in his Know your Enemy: ANPO

in Art in America (January 1, 2011).

Here are my notes. I thought initially to write them in 140-character twitterese, but even that defeated me.

- The featured/interviewed artists reported many motivations for their earlier activism, ditto their attitudes about the U.S., U.S. servicemen, &c. Protesters in 1960: right and left wing, workers and students, teachers and taxi drivers, mothers, fathers, veterans. people of all stripes.

- Their motivations — and the rationales they might have given at the time, for their actions — do not reduce well to a single political or ideological idea, although the film suggests they do.

- Still,

dignity

comes to mind. That might translate to some (not me) asnational pride.

- To put the history in twitterese: Kishi sells out Japan to U.S. People discouraged. Ikeda sees their energy, harnesses it to developing economy. Result: The Japanese Miracle.

- By focusing on figurative/representational arts — some with a surrealist inflection — the film necessarily shows what can be seen. The historical. The visible.

- A record of crimes : fire and nuclear bombings, police brutality, rapes. Burnt flesh, broken bodies. CIA financing of the LDP. Victims victims everywhere.

- What we can’t see — what is invisible to the camera — is what is left out.

- The forms of that cost are intangible, invisible: Absence of government accountability, transparency. Absence of energetic debate/argumentation about the constitution, role of military.

Short bios, and examples of their work, are provided for each of the artists featured in the film here (in Japanese); bios only, for fewer of the artists, here (in English). For some of the paintings, video pans across the work, showing details, may well be the ideal presentation, one that is closer to the artist’s experience of making the things, detail after detail.

- Printmaker Kazama Sachiko (風間サチコ) said something about a government, that does not protect its people.

- The Okinawan artist/activist Ishikawa Mao (石川真生) talked about how Japanese reinforce the fences, the sense that it is

natural

to have the bases in Japan. Who does she hate the most: not American soldiers (she said, anyway), but the U.S. military and government, and above all the Japanese government that keeps them there, and Japanese people who allow this to happen. - Tadanori Yoko (横尾忠則) is smart and funny, would love to hear him reminisce. He confesses to having not been very clear in his own mind, at the time, about his objectives or ideas.

- Photographer Ishiuchi Miyako (石内 都) talked about growing up in Yokosuka, location of an American naval base. The work that was shown was her stunningly beautiful and sad photographs of clothing, much/all of it in tatters, that came through the Hiroshima atomic bombing. Search

ひろしま 石内 都

for examples. That said, the film’s emphasis on the atomic and fire bombings were overdone in this film;no more war

can not have been the sole motivation of the protestors of the U.S.-Japan treaty. - Ikeda Tatsuo (池田龍雄) says,

the point was to change minds,

to which he adds that he has no way of knowing if they achieved that aim. - Back to the costs.

There’s a trajectory arc that leads from 1960 to the present, 50 years later. The shock of the tsunami followed by the nuclear reactor failures are prompting rethinking about the country, where it’s come from and where it’s going. The photographs of destroyed towns bring to mind scenes of wartime bombings. It seems also like most of the people we see in those photographs, particularly in shelters, are of the elderly, as if it’s only the elderly who remain, in dwindling numbers, in the countryside.

The costs of ANPO, and of the social compact to work hard, save, consume, trust in the government and business, and behave, may be surfacing.

Beaten down, scholars say, many young adults have turned inward or timid, so much so that Japanese have coined terms to describe this condition: hikikomori, social withdrawal; soushoku danshi, literally, herbivore men.

— in Don Lee and Julie Makinen, Japanese see disaster as opportunity for broad change (Los Angeles Times, 11 April 2011).

That article discusses the need to decentralize government and other functions, and to reform immigration policy. It also suggests that there may be new impetus to address pent-up problems.

Another indictment of policies, again focussed on demographics, appeared in the New York Times a few weeks prior to the tsunami: Martin Fackler, Japan blocks the young, stifling the economy (27 January 2011).

Obviously, ANPO is not the sole key to addressing these problems. But there was corruption in the system from the start (going back to late 1940s). It’s often observed that it takes an external crisis to budge Japan in any direction. We’ll see if the current reflections lead to a review of ANPO. This is certainly viewed by many as a Pandora’s Box best left alone, for it would probably lead to a rethink of Article 9 in the Constitution, and reframe thinking about how to get along with the neighbors.

dignity

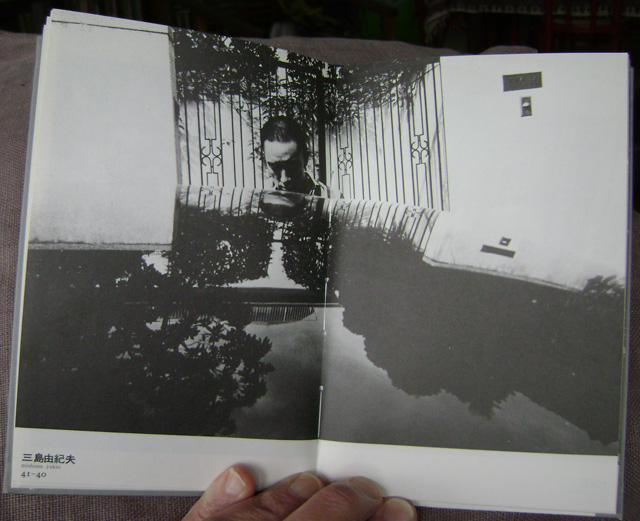

Yukio Mishima in front of his house, in Takanashi Yutaka his Jinzo

(1979), pp40-41.

I pulled out Takanashi’s Jinzo (1979), with its several images of Mishima. The first is in front of his entryway, reflections on a fancy-looking car. A few at the gym or sento, beautiful form in grungy surround. The last is Mishima in his bed, in his perfect bedroom, (his?) books aligned perfectly along the wall. In his life and particularly his death, Mishima represented something that Japan was losing: an ambitious commitment to beauty and perfection.

The right and the left both have been troubled by Mishima: great writer, but an embarrassing clown, critical of the emperor, follower of bushido. I look at his suicide at Ichigaya in 1970 as a performance — an act of aesthetic purity and dignity, and indirectly, an indictment of a culture devoted to consumption and easy satisfactions.

飢餓海峡 (Kigakaikyo), 1965

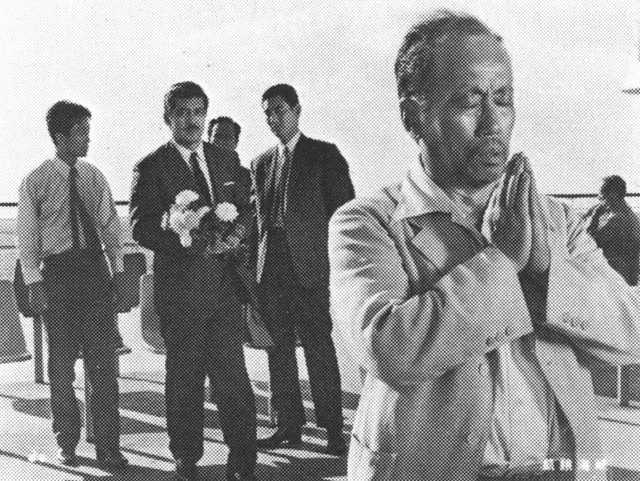

Uchida Tomu (director) Kigakaikyo Fugitive from the Past / Hunger Strait

(1965). This image differs somewhat from final scene in the film. and is taken from フィルムセンター所蔵映画目録 (National Film Center, Film Collection Catalogue), listed here.

Detective Yumisaka (Ban Junsaburo) is a provincial detective who is determined to bring Mikuni Rentaro’s Takuchi Inukai, an escaped prisoner, thief and murderer, to justice. Inukai vanishes, remakes himself as Kyoichro Tarumi, a pillar of a community. No one asks hard questions about his past; everyone has a past, everyone is on the make. Yumisaka gets only so far in his investigation when the trail runs cold; it is picked up again later, by another detective (played by Takakura Ken). Notwithstanding the evidence, it will take a confession to bring Mikuni to Justice, however.

The film was made roughly when Takanashi and friends were out in the streets with their cameras, recording the mundane reality of the Japan Miracle. The crime that is portrayed in the film happens in the 1950s; but the revived investigation takes place in the early 1960s.

I first saw Kigakaikyo in a packed Kyobashi Film Center in 1983 and have long pondered what it might have meant to its mostly young audience (at that screening, anyway). Surely the film presented them a story about a repressed past — something that their own parents may have put out of mind — that must ultimately surface.

Cast and other information on the film, along with several reviews, can be found IMDb. Some rate this their top Japanese film. I particularly like One of the great narratives of bad karma, hell, of cinema,

posted 19 March 2011, in which chaos-rampant

writes Our past actions have brought us here, our present actions determine our future.

Yumisaka prays, Takichi Inukai (aka Kyoichiro Tarumi) approaches; final scene, Uchida Tomu (director) Kigakaikyo Fugitive from the Past / Hunger Strait

(1965).

I bring it into this discussion because of the last scene: the wake of the ferry. As with Takanashi’s images of the waves near the power plant at lands edge, as with recent tsunami, the sea (nature) cannot be forever denied.

final scene, Uchida Tomu (director) Kigakaikyo Fugitive from the Past / Hunger Strait

(1965). Apologies for bad quality, these are photos of VHS version.

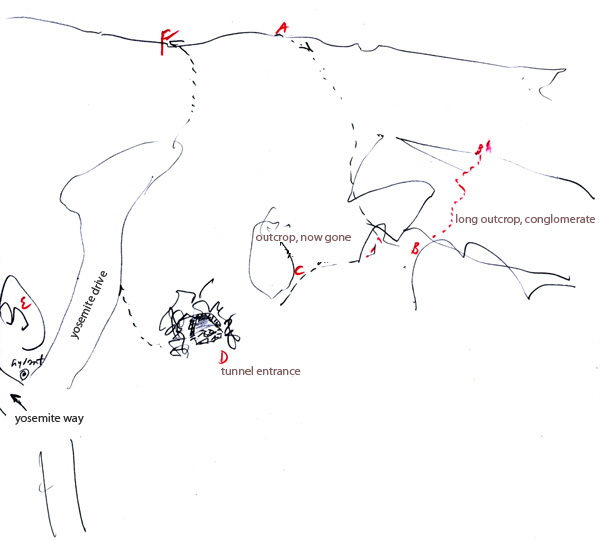

an Eagle Rock water story 14 January 2011

In Myriad Unnamed Streams,

her fascinating web essay of water stories in Northeast Los Angeles, Jane Tsong writes —

I discovered that small springs and seeps were common and perhaps known most intimately by adventurous local children... Such small waterflows were never mapped, much less named.

I’m from the same neighborhood — Eagle Rock. I remember not a water flow, but a water tunnel or perhaps cistern that I, together with my sisters and brother and probably other kids in the neighborhood, visited from time to time in the late 1960s. It’s long gone, to make way for lots that currently stand empty, probably directly under West Fair Park Avenue (which didn’t exist then, unless it was a driveway or dirt track), and downhill from the end of Yosemite Drive. The lot may have been an estate once; I recall something like an orchard, or the remains of one, closer to College View Avenue.

View Larger Map

This note is less about water, than about one of our expeditionary routes from home.

We lived on Round Top Drive, above the end of Lockhaven and looking out toward the San Rafael hills and the San Gabriel range beyond. The hill had once been known as Round Top. We moved in to what the developers called an Emperor

style-home in Glendale Eastridge, when our section of the tract was completed in 1964. The lots were clean-scraped dirt. We were refugees from a house on Hill Drive across the valley, one of many that were taken to make way for the 134 extension.

The tunnel was one of the stations

on our childhood expeditions in that direction, along the ridge above Lockhaven, east toward Loy Lane, and down at point A into the ravine.

Conglomerate outcropped here and there; some still remains (judging from the Google satellite view). A long steep piece ( B ) roughly paralleled College View, close to Loy Lane. Another ( E ) stood at the head of Yosemite Drive. We used to climb over both. The first was more dangerous and challenging; the second had a couple of holes in its face, that we’d perch in, spy-like above the Yosemite Road/Way Y. A big (enormous) piece of that rock used to sit below it, to the right side of Yosemite Way as you walked/drove up. It’s gone now, a house in its stead. My sister Margaret recalls water seeping out onto the road, and thinks it does so still.

We might start our circuit by clambering up or down B. We may even have used rope for that one. All of us remember a somewhat older and very intense boy there, one afternoon, who was showing off, fell and got scratched terribly, and painfully pretended it was nothing; Catherine remembers him as scary. From there, we’d walk down the hill, skirting another rock, now evidently gone, at C.

And finally we’d arrive at the mouth of our water tunnel at D, semi-hidden under brambly shrubs. It might have been five or six feet across. There was always a few inches of water inside. To enter, we needed to stoop; to stay dry, we needed to step carefully on rocks and rubble. I don’t remember there being mosquitos. The arched ceiling was brick, in memory at least, and at least at the entry. It went back a ways — seven, ten feet? and then turned left? We never went in too far. We’d persuade the younger sister, Catherine, to go in the furthest. She doesn’t remember it.

I wonder today, more than 40 years later, at our/my failure to drain the thing and explore its deepest recesses. Circa 1970, the tunnel mouth was completely overgrown; I never returned.

whither/wither hardware

3 December 2010

Saturday late November out in Long Beach, walked with my artist-painter cousin Moira and her Louma/Technocrane engineer-husband Mark over to Village Cafe for a midday breakfast. There’s a nice little concentration of businesses there — post office (90808), hardware store, restaurant, tavern, bookstore (or two?), shoe store — a small town where I wasn’t expecting to find one. I had the Mexican omelette (with sausage), Moira Greek, Mark something normal. All delicious.

We passed a hardware store on the way over, and went in on the way back. It’s located next to the post office, minimal exterior signage (and even that perfunctory, an old Ace Hardware sign, with the ACE painted over). A display of new trash barrels and the like, out in front, indicated that there was life inside and the store was open for business.

Roses is compact, densely stocked: as if the storeroom in a ship. Being a tourist with no immediate needs, I didn’t wander the aisles. But the store looked and smelled right.

Owner Dave Hussner was in back, pondering. He knew of McVey Hardware, Pasadena Hardware, all the old businesses many gone. Roses was, until recently, an Ace Hardware store, but he’d pulled out of that: their programs made no sense for him, in this or perhaps any economy.

Said he doesn’t talk as much as he used to, because it’s not wanted, really. Today’s customer knows what he/she wants, a brand mainly, or a specific model number. No other will suffice. And so Dave answers specific questions, e.g., why the top no-step shelf is plastic, what the rivets are made of. But he doesn’t sell to people who don’t want his thinking on the matter at hand. Customers don’t want to see a judiciously curated selection of three shower heads; they want to see all 25 of the variations currently on the market (and at Home Depot), that they’ve already read and come to a decision about. There’s no real selling involved, and no respect for the retailer’s judgement.

We talked about tone, about what I call hardware store

humor, laid back, deadpan, possibly deriving from the Midwest from which many Angelenos came a century and more ago.

I mentioned Victor’s resistance to John Cotter’s True Value

system, which he viewed as a form of collectivism. Hussner thought about that and chuckled, agreeing that hardware store owners were an independent lot, who liked to do things their way. If it’s not fun, why bother?

Hussner was pessimistic about hardware retailing at this scale, anyway. He related the view of one salesman, who opined that no real hardware stores remained in all of Los Angeles. That seemed to both of us a stretch, but certainly much has changed.

Hussner, like other hardware store people I’ve encountered, is less romantic than he is pragmatic and realistic about his business and the prospects of the retail hardware store genre he practices. Romantic views of the family,

mom and pop

(and how I hate that expression!), and-old fashioned hardware store are a luxury, an indulgence for people outside the business, reporters, homeowners who take their trade elsewhere and realize, too late, what they’ve lost.

Maybe the cycle will come round, economic shrinkage will return us to our senses. But that’s probably wishful thinking. We talked about a throw-away

economy in which nothing’s worth fixing — better to buy a new one. The labor isn’t worth the time. Only the day before, I’d talked at Victor’s memorial service of fixing bicycle sew-up tires, or dismantling, cleaning, regreasing and packing, and reassembling hubs and derailleurs. Few of us would do this today, when even shining shoes seems a lost art.

And yet, and yet. Roses is loved by customers, has good reviews on yelp, for what they’re worth. Glad we walked in there.

more on curating —

Surely, a well-curated selection is the hallmark of a good business, and good retail is crucial to the quality of urban living. Why then this resistance to curating, by consumers who won’t trust and don’t want the advice of the retailer. What’s missing? Why this failure of confidence? What might be done to restore it?

And yet, curating might not be the right concept for hardware stores — or many of them. How much curating can a 3/8 inch, 5 inch length carriage bolt endure? At best, the curating can happen at the margins, for those items where competing solutions, or styles, might be found.

The going is even rougher for stationers. Their numbers decline, and fewer and fewer people have ever seen, still less entered, a stationery store. Young people think Staples

or OfficeMax,

if anything at all. This leads me to reflect on the mutability of retail genres, but that’s another post.

4823 19 August 2010

composite iPhone view, Eagle Rock Valley (western portion), San Rafael Hills, San Gabriels (credit: Kuniko)

Move cursor across the image : telescopic view (should) appear below (perhaps not immediately).

These weeks since return from Material Cultures in Edinburgh have been hectic: preparation of the entry below on the Coit-Silsbee Theological Common Place Book with a copious index (1832); three days of Chisaku’s swim meet in Gardner; several additions to the directory of telegraphic code scans and examples; looming return to the classroom; a journey to California.

Saw family in Los Angeles. My father recently left the home in Eagle Rock from which the above panoramic view sustained him daily for some 46 years; my own last act on the property was to leave the hose on trickle under the avocado tree down the hill. Kumquats are at right; a few remain in the refrigerator here in Cambridge. Also enjoyed conversations with Eric Warren of the Eagle Rock Valley Historical Society, with whom I exchanged images and stories.

In Berkeley, visited Serendipity Books (where I worked ca 1975-82); too big, too many, too much but, providentially recalling my interest in Gertrude Stein, found two volumes to buy, and Frances Butler on shadows. And then on to see Peter and Alison Howard, both in lively decline. When we arrived, they separately reclined in the living room in something like an eighteenth century scene (though no tears), where after greetings Peter resumed his read aloud and from deep withinward, Muriel Barbery her Gourmet Rhapsody the passage about grilled sardines. A careful, intelligent reading, picking at every word as if separating fish from bone. Early man, in learning to cook fish, must have felt his humanity for the first time, in this substance where fire revealed both essential purity and wildness... Meat is virile, powerful; fish is strange and cruel. It comes from another world.

Peter finished the chapter and we talked, talked about it matter naught what — Kerry’s Bob the turkey

(a small remnant of whom might be the day’s lunch), her pig too, who loved by the neighbors wanders free and rightly fearless; about Chisaku’s swimming; and winding the clock on the mantle; about the new garden next door; at length about a Tibetan manuscript (and the question Why?

behind it all). Sadly, a week later, Alison is gone.

We caught up with other long-standing and gracious friends in Berkeley, Oakland, San Francisco. David and Hanne, Bob, Paul, Alastair and Grace, thank you all. What else? Took the ferry from Oakland. Visited Australia Fair (on Bush), and the Cartoon Art Museum (Mort Walker’s Beetle Bailey, work by Nina Paley). Went to Muir Woods. Toured the new C. V. Starr East Asian Library at Berkeley.

We’d driven up 5 but returned via 101 — first time in many years — through the Salinas Valley and on to Santa Margarita, where we turned east onto 58 for the 82-mile trip to Buttonwillow, then back onto 5 for the climb over the Grapevine. 58 was a fascinating drive, through nascent wine country, up into cattle country and finally, after miles of complicated nothingry, through oil fields in the hills and the latter-day wild west town of McKittrick. Interesting and varied (ocean-formed?) terrain that warrants a full chapter in Roadside Geology of California, and warrants a protracted return too. I see belatedly that the San Andreas Fault runs through Carrizo Plain National Monument (quite a story); also, that a location called Asphalto lies immediately east of McKittrick. Next time.

Before departing Los Angeles, we visited the E. Hadley Stuart, Jr. Hall of Gems and Minerals, the high point of an afternoon at the LA County Natural History Museum. We also visited the Museum of Jurassic Technology and, next door, the offices of the Center for Land Use Interpretation at which, remarkably, a digital slide presentation (at several different stations) of Through the Grapevine: Streams of Transit in Southern California’s Great Pass was on view. Good timing (though, alas, I missed the CLUI bus tour of the same area by one day!)

Edinburgh 19 August 2010

Recorded here are thoughts and extrapolations prompted by some of the presentations I heard at Material Cultures 2010. The full program includes links to abstracts (alas, separate PDFs). For the most part, and reflecting a temporary state of mind (and zero subsequent regrets), I stayed away from sessions that announced themselves as e

flavored. There was enough of that in the plenary sessions.

In Session 1A on Reading and Sociability, Susann Liebich described an epistolarly exchange between Fred Barkas, a middle-class New Zealander living in Timaru between 1909 and 1932,

and his daughter Mary during her travels in Europe (with her mother Amy, Fred’s estranged wife) and while living in London. Liebich’s paper, Intimacy, Friendships and Reading in Early Twentieth-Century New Zealand told a fascinating but ultimately sad story. Barkas appears to have been an energetic and constant

reader; later, he seems to have reformatted his daily letters to (and from?) his daughter into a kind of typescript newsletter (for whom was not made clear) — perhaps this was his Some Memories of a Mediocrity that Liebich showed. Reading and reports of reading were a constant in the epistolarly relationship between father and daughter. I asked if there’d been cables sent between them (using the reduced rates available for social messages through the Red Line

); yes, there had been, for communications warranting it (e.g., about the mother’s doings). But those cables were not incorporated into the newsletter. Something about the form, perhaps, or content, kept them out.

I find a photograph of Fred, Mary and his wife Amy in their garden (in 1891?), here, being part of the Memoirs of Frederick Barkas and the Barkas family scrapbooks and papers, all in the National Library of New Zealand. Liebich’s point: the reading, an aether through which Fred and Mary’s love was modulated and flowed.

I couldn’t help but dwell on the relationship of forms and communication, which lies at the center of telegraphic message practice involving codes, during Peter Stallybrass his plenary talk. By Printing and the Invention of Manuscript he suggested that much handwriting was/is done because printing demanded it: tax forms, census forms, blanks to be filled in, signatures to be provided. There was an explosion in production of printed forms designed for completion by hand. Sticking here to my own obsession, forms with blanks tend to structure communication in ways that are convenient for telegraphic communication, with its word-count pricing. Moreover, the step-by-step assembly of a message ensures that important information is not inadvertently left out. Some telegraphic codes incorporate forms external to the book itself, instructing the message sender to enter terms (in code or plaintext) in the order in which said form provides for them.

Because this conference was in Edinburgh, I thought it only right to attend Session 4B on (Post)Enlightenment Scotland. Good choice. In his presentation Intoxicated with this Delightful Performance

: The Culture of Critical Reading in Enlightenment Scotland, Mark Towsey talked about the Literary Journal

of Alexander Irvine of Drum (1777-1861), a reading diary covering five years while in Edinburgh for his education. Alexander is inspired by Gibbon’s account of his regularity in study.

He reads legal commentaries, political and natural history — some 100 separate titles are mentioned, drawn from libraries, friends, his own collection. Alexander tries Sterne’s Tristram Shandy but finally gives up. His labors are challenged by lack of self-discipline, a liking for food, drink and women, and ill health and poor eyesight. Still, his is an unwittingly heroic effort to become gentleman and scholar. I conclude from Towsey’s delightful account that (1) reading is not so pure a state, but rather is subject to, or is itself but one among many, distractions in life; (2) reading is less natural than it is unnatural, always a struggle, with different intensities during the curvilinear course of one’s life; and (3) Alexander understands Sterne more than he could know — indeed, was a Shandyan himself. Finally, Alexander was an inventive and energetic writer: I hope to find occasion to slip his expression difficulted by

into my own wordhoard.

In Session 5A on The Organisation of Texts, two presentations were made on commonplace books (I was once listed for this session, later and mysteriously removed to another). In her presentation Memorial Genres: Commonplace Books and Poetry Anthologies in Nineteenth Century New England, Amanda Watson showed a variety of such volumes, including usages of John Todd’s Index Rerum; many of these included tables of contents or indexes. Watson used examples at Brown, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and Houghton Library, all of them identified as containing poetical extracts; my own corpus was assembled arbitrarily and accidentally: the copies of John Todd’s Index Rerum that came into my possession over the last decade or so. Watson also took a census of poets encountered in her anthologies; several of them (quite forgotten, today) were familiar to me from the extracts in my own copies. Questions were raised (from the audience) about whether the term commonplacing

— associated with Renaissance rhetorical and organizational practices, Erasmus, etc. — could rightfully be used to describe these books. (One recalls Ann Moss in her concluding chapter Seventeenth Century: Decline,

where she discusses — or laments? — downmarket

improvements to a device that no longer employed a pre-existing conceptual grid

(1996:279).) Yet 19th century users had no qualms about this as they turned their commonplacing and indexing to their own purposes.

In the same session, Vera Keller discussed Francis Bacon’s program to include things lost or barely there — the marvelous, the every reputed possibility,

things just about to fall out of being — into his scientific program. Her Accounting for Invention: Book-Keeping and the History of the Wish List led us into some fascinating material, starting with Guido Panciroli (1523-1599), his History of Many Memorable Things Lost, which were in use among the ancients:

and an account of many excellent things found, now in use among the moderns, both natural and artificial (being the 1715 English translation, of the book originally appearing in 1599-1602). The list of lost things pointed to the future as well; (1) a thing, if lost, might be rediscovered; and (2) a thing known now, might eventually be lost. And so the need to recover and record, and to organize these as if in columns of debts and credits. Writing this now, I think of Aristotle’s De Generatione et Corruptione (Greek edition here), and Gus Blaisdell his essay accompanying Lewis Baltz’s Park City, where he develops an argument from Aristotle’s assertion about philosophizing about dust, and hair, and other things beneath notice, nigh beneath thingness. I digress, but only to bookmark for myself Keller’s bringing into view this material and ideas.

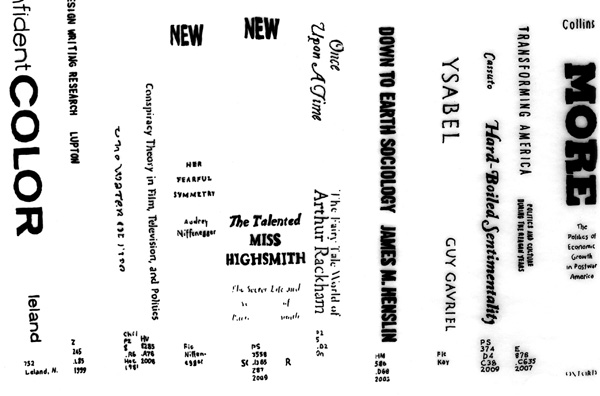

Session 8A was devoted to Print and Identity. All three presentations were of interest to me. Iain Stevenson talked about the banknote design of William Home Lizars (1788-1859), engraver (in steel and copper) and painter. Stevenson got into Lizars by way of his cartographic engravings, and was struck by the complexity and high quality of his banknote design, whose influence is evident today in American currency. The complexity of a design is one guard against forgery; the sheer quality of the art also seems to imbue a banknote with vertú. On the same panel, Jennifer Nolan-Stinson discussed her work with avid readers

in a presentation entitled Living with Books: How Books Are Used to Construct Identity in Domestic Spaces. She focused on the arrangement of books in (different rooms) in homes, and the roles that presentation plays in individuals’ definition of themselves as readers, as well as how they wish to be understood by others; the corollary is how one perceives others by means of their selection and presentation of personal libraries. My own reflections on her talk were influenced by my father’s recent move to assisted living, and his (and his family’s) efforts to jettison books and other objects. And so I thought that one’s relationship to physical books, one’s organization and deployment of them in the house, probably evolves over the course of one’s life. Nolan-Stinson didn’t explicitly get into the life history

aspect of her work in this talk. One member of the audience wondered about the possible impact of Kindle and other e-readers. That got me to thinking about alternative means of presenting a personal library, e.g., by means of e-wallpaper, where one might present the spines of books that one once but no longer owned. One might rearrange the presentation depending on guests or mood, or for much the same reason one might rearrange one’s physical library from to time. My thinking here was influenced in part by work done by one of my students, shown below.

detail, tracing of lettering on spines of books as they appeared on a bookshelf, Dana Martin, for Design Stories class, Montserrat College of Art, Spring 2010

Another dimension to the issue — and here, yes yes I digress — books and book shelves are a mirror of one’s life: the books one’s read or not, tried to read, failed to read, read more than once. They mirror aspirations and failures, hopes and achievements. They are an aid to memory of one’s own life. Here, I could not help but think of Microsoft’s Sensecam, a small camera/display device worn from around the neck, whose applications include prompts for people with failing memories (e.g., with Alzheimers) — a picture of your wife, the front of your house, your name, your children. Sensecam is described in the New York Times and here at the Microsoft Research SenseCam site.

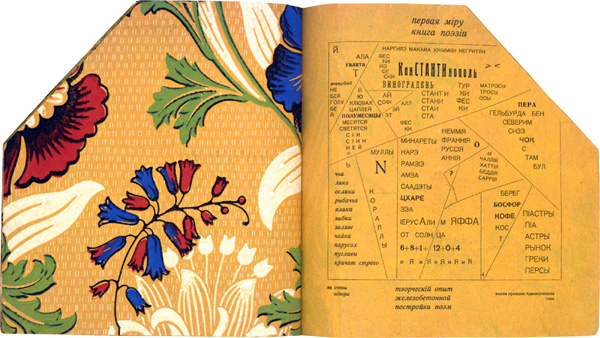

I’ll conclude these notes with comments about the first of the three talks in that same session, Maria Pasholok her A Perfect Place to Read: Transformation of Reading Space in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia. Something must have changed between the abstract

of this paper, and the talk we heard, but the in-between pieces were fascinating. A good part of the talk was devoted to the so-called wallpaper poets

whose books were either covered in, or fully printed on (the back of), wallpaper. These included Vladimir Burliuk, Nikokai Burliuk, Elena Guro, Vasilii Kamenskii, et al, their Sadok Sudei (A Trap for Judges) St. Petersburg, 1910 and Vasilii Kamenskii his Tango s korovami: zhelezobetonnyia poemy (Tango with Cows: Ferro-concrete Poems) Moscow, 1914. Tango with Cows has an angled design (five sides) that apparently reflects the floorplan of the room in which it was written.

spread from Vasily Kamensky, Tango s korovami: zhelezobetonnyia poemy (Tango with Cows: Ferro-concrete Poems), from PDF available via Russian Avant-Garde Books at the Getty Research Institute.

So there’s an inside/outside shift, the wallpaper of interior space, becoming the exterior of a book. At one point, Pasholok rushed without pausing through a few slides to get to her concluding cartoon (Gogol goes with the chest, Zola with the armchair, but where would Cervantes — the servants — go?). Among those that flashed before us was, I think, a view of Rodchenko’s Worker’s Club reading area, which was fabricated and exhibited in Paris in 1925.

view of reading area, Aleksandr Rodchenko, Worker’s Club, exhibited at the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, Paris, 1925. Taken from one of numerous instances online: the original is in the A. Rodchenko and V. Stepanova Archive, Moscow.

The glancing view prompted a thought about this instance of a social condenser.

Here is a highly efficient recharge station, to which workers might come for a fix not of fuel or pure oxygen, but pure reading of Lenin-approved texts. I emphasize pure, the idea that there is such a thing as pure reading, something that can be named and programmed. Moreover, here, reading became public, a display, a performance as a Soviet worker. And I thought, there would need to be quite a cleaning-up of the idea of reading for this to happen, a redefinition that would exclude a lot (like reverie, time-wasting, the distractions that beset Alexander Irvine of Drum in his own reading program).

There’s a another aspect too: reading is removed from the private sphere to the public. The inside/outside mechanism involves an oscillation between private and public. Is the Revolution (and some Soviet avant-garde art) concerned with projecting the bourgeois private sphere out into the street? And so wallpaper is taken out of the closet, as it were? Naturally, because we’re talking about people, the private can’t really be ended, only displaced : it will crop up in new places, new undergrounds, new forms. Pasholok’s talk about the spatial life of reading was, by virtue of its fragmentary quality, engaging.

The last day I wandered. Here, on Old Tolbooth Wynd, I ran into Richard Smolinski and Linda Carreiro, with whom I (and Ashley Whamond) shared a table at the edge of the conference banquet. That’s them in the distance, unrecognized still, coming my way.

Old Tolbooth Wynd, Edinburgh, 19 July 2010; same place via google.

We talked about Richard’s participatory and other performances, and about the Museum at Surgeon’s Hall I’d just come away from, which exposed Linda’s vast working knowledge of these museums’ holdings around the world.

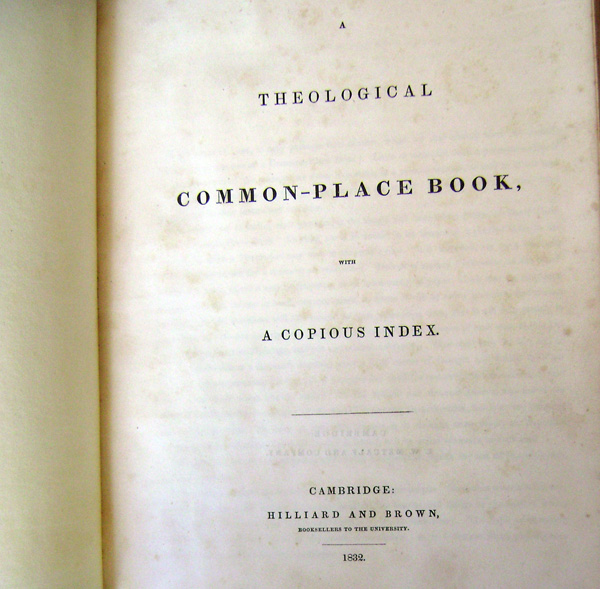

...with a copious index 4 August 2010

bMS 558 William Silsbee, Theological Common Place Book, 1832 (Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School)

contexts

Thomas Winthrop Coit, 1803-1885

William Silsbee, 1813-1890

Preface to A Theological Common-Place Book

references

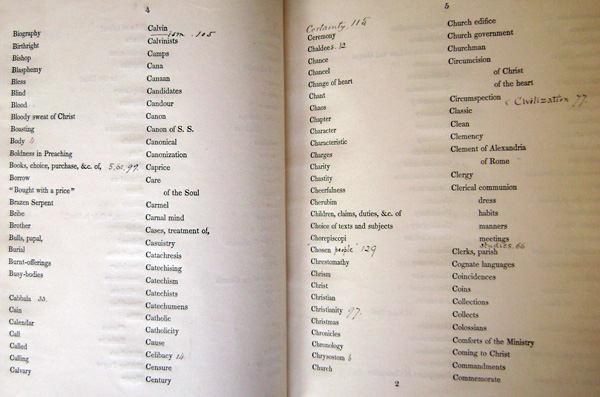

Into A Theological Common-Place Book, one indexed his or her reading, particularly of those passages to which a Theologian may wish to preserve a clue.

It is mostly a blank book, save for its title, a two-page preface and 31 pages of a copious

index, listing 1,855 pre-selected terms, two columns per page. Pages are not numbered beyond the two prefatory pages (iii-iv) and the index (1-31). But counting 16 signatures of 24 pages each, it totals 384 pages, approximately 350 of which are left blank for the owner. It is a substantial tome.

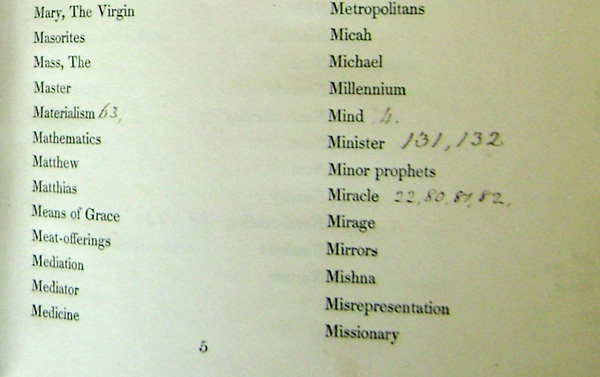

How does it work? Our reader William Silsbee (about whom more later) encounters a passage to be indexed. He considers which one (or potentially more than one) of the printed index terms best characterizes the passage. Miracle fills the bill.

bMS 558 William Silsbee, Theological Common Place Book, 1832 (Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School)

He turns to the first available blank page, or page with sufficient space, in which to make his notation. The first blank pages follows page 21. He writes 22 atop that page, and the same number 22 next to the index term miracle. He then proceeds back to page 22, where he makes his notation. As can be seen above, Silsbee would have further occasion to add references or extracts concerning Miracles, on pages 80, 81 and 82.

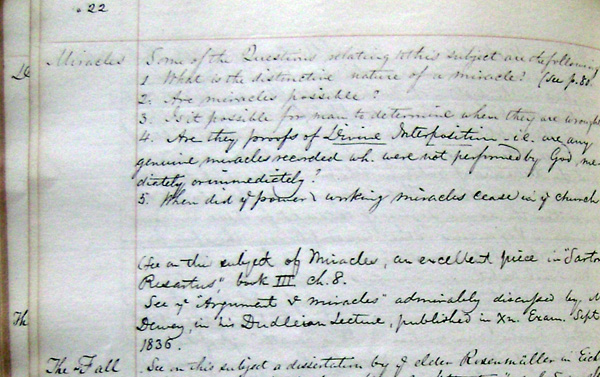

bMS 558 William Silsbee, Theological Common Place Book, 1832 (Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School)

But Silsbee’s entry under the head miracle does not only point to a source. We have a list of questions relating on this subject,

followed by footnote-like references to Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus (Book III, Chapter 8) and Orville Dewey’s Dudleian Lectures (presumably his A discourse on miracles, preliminary to the argument for a revelation :

being the Dudleian lecture delivered before Harvard University, May 14th, 1836 (First printed in the Christian Examiner,

Cambridge, [Mass.] : Folsom, Wells, and Thurston, 1836), and reprinted here). Finally, there is an onward link,

so to speak, to Silsbee’s own further notes on miracles at page 80.

bMS 558 William Silsbee, Theological Common Place Book, 1832 (Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School)

An ongoing search for sources and analogues to John Todd’s Index Rerum brought me to a mention of a Cambridge Theological Common Place Book

in the preface to John F. Ames, his The Mnemosynum (1840). The Cambridge Theological Common Place Book

is in fact The Theological Common-Place Book, published in Cambridge in 1832. Thomas Winthrop Coit is not named as author in that edition. Searches in Google Books, WorldCat and elsewhere lead to clarity.

The first edition of A Theological Common-Place Book is promoted — and the author identified — in a review in the Banner of the Church (Saturday, April 21, 1832). A Third (1857) edition is announced, and the author again identified, in The Churchman’s monthly magazine 4 (1857). Allibone’s Critical Dictionary mentions this among other of his productions in its entry for Coit, Thos. Winthrop,

here. WorldCat mentions a 4th edition in 1860 (New York: Daniel Dana; 23cm high) but does not otherwise identify the book, or even point to a library holding.

Ames is promoting his own system. He approves Todd’s Index Rerum as far as it goes — presumably because it is general, not tied to a limited index vocabulary. However, Todd does not provide space for extracts, where extracts may be needed. It not infrequently happens that we read books of which there are but few copies — or they may belong to libraries to which we can seldom if ever have access.

Moreover, one would be wise to make quotations from papers and periodicals, which in many instances are not preserved

or are difficult to obtain. Ames’s improvement, then, is to provide a means for making extracts or longer bibliographic entries on numbered sheets, and for indexing all of these in tables, using the Lockean first-letter, first-following-vowel system to point to the page on which the extract is contained. His system is more flexible than Coit’s — by adopting the abstract Lockean alphabetical system rather than Coit’s 1,855 heads — but allows users to write extracts as long as needed, which is not unlike Coit’s blank pages.

an aside — Here or elsewhere, and when time permits (but soon!), I will look at variations/improvements on Todd proposed by William Augustus Guy (1841 and 1854, involving loose sheets, each one given over to a subject, that might be further broken down in subdivisions of proposition, hypothesis, theory, etc.) and Joseph Gowan (1902, again, loose sheets), among others. These point to index cards, early information retrieval

systems (e.g., Zato Coding), etc.

The great advantage of Coit’s system is its restriction to a single domain (in this instance, theology), and its consequent provision of a disciplined and controlled vocabulary of index terms. Coit writes, The mere turning over the pages of this Index, and pausing here and there upon the titles which cover them, will not be without its advantage.

Indeed, with growing professional specialization, controlled vocabularies and greater space given over to specific topics, would seem a logical solution.

The preface to the so-called Semi-Centennial

edition of Todd’s Index Rerum (1883) acknowledges a change in focus. While formerly the aim of the student was to be informed on all subjects of general interest and importance,

this will no longer do. The successful man of to-day is he who is content to be ignorant of many things, in order that he may know a few things well.

James M. Hubbard, who revised the book, suggests that two or more references under different headings be made to the same book or author, and suggests that certain pages at the end of the book be devoted to specific subjects. For example, one might make a reference from the body of [a] book, as, under Ci, Civil-service reform, see Appendix.

Parsons/pastors routinely maintained commonplace books as an aid to preparing sermons. Coit’s and Todd’s books (of 1832 and 1833, respectively) both sought to facilitate the practice, and both appeared amidst a growing offering of skeletons

and sketches

of sermons, that might today fall under the larger heading of lectionary aids.

This illustration gives a sense of that undertaking —

The preacher should make careful and extensive preparation in respect to pulpit themes. His common-place book of texts should be a large volume in the outset... Instead of buying volumes of skeletons that are so frequently offered at the present day. It was formerly the custom, in an age that was more theological than the present, for every preacher to draw up a body of divinity

for himself — the summing up and result of his studies and reflections. Every preacher knew what his theological system was, and could state it, and defend it... Whether or not, the preacher imitates this example of an earlier day in regard to theologizing, he ought to in regard to sermonizing... Let him pursue this business of selecting, examining, decomposing and recombining textual materials, with all the isolation and independence of the first preachers...

pp536-7, William G. T. Shedd, The Different Species of Sermons, and the Choice of a Text,

in The American Presbyterian and Theological Review. New Series, No. XVI. October 1866 here.

By providing the index terms, Coit’s book echoes printed (but largely blank) commonplace books of centuries before. I’m thinking here of John Foxe’s Pandectae locorum communium, praecipua rerum capita & titulos (A Compendium of Common Places, with the Heads and Titles of the Principal Things; London, 1572). William T. Sherman discusses a copy of this book, now at the British Library, that was intensively used over many years by Sir Julius Caesar (1558-1636), a lawyer and high civil servant (Sherman, Used Books : Marking Readers in Renaissance England (2008)). The book provides 768 topics in its index and in the running heads; to these, Caesar adds 682 items, some extending the terms already provided, but many introducing new topics entirely, that were relevant to his professional needs. (This paragraph added on 29 August 2010, prompted by Whitney Trettien’s mention of Sherman on Foxe’s Pandectae here.)

The New York Times ran this obituary of Coit on 23 June 1885:

The Rev. Thomas Winthrop Coit, D.D., died at Middletown, Conn., Sunday night. He was the eldest son of Dr. Thomas and Mary W. Saltonstall Coit, and was born in New-London June 28, 1803. He was graduated at Yale in 1821, entered the ministry of the Episcopal Church, and became successively Rector of St. Peter’s Church, Salem, Mass., in 1827; of Christ Church, Cambridge, Mass., in 1829, and Trinity Church, New-Rochelle, N.Y., in 1839, and still later, of St. Paul’s Church, Troy, N.Y. Since 1854 he had been a Professor in the Berkeley Divinity School, and resigning his rectorship in Troy in 1872 since resided in Middletown. Dr. Coit was among the foremost scholars of the Episcopal Church, and was the author of several able works in defense of its doctrines and position. Besides a large number of addresses, sermons, and contributions to the church papers and reviews, he has left a large library filled with marginal notes made in his beautifully clear handwriting that is of inestimable value to its present owner, the Berkeley Divinity School.

Coit was in Salem Mass, and again in Cambridge, in years during which William Silsbee would have been in both places. It is likely that Coit’s marginal notes

found their way into his own notebook/commonplace books, and even yielded his copious index

of 1832.

From the description of bMS 558 (William Silsbee, Theological Common Place Book, 1832.)

Rev. William Silsbee was born in Salem, Massachusetts, May 17, 1813. He received the A.B. degree from Harvard in 1832, and graduated from Harvard Divinity School in 1836. He was ordained a Unitarian minister in Walpole, New Hampshire in 1840 and served at churches in Northampton, MA, Melrose, MA and was pastor of a church in Trenton, New Jersey from 1867-1887.

Silsbee is described as Transcendental

in Alfred F. Rosa, Salem, Transcendentalism, and Hawthorne (1980). Silsbee lectured on Aesthetic Culture

in the seventh course (1836) at the Salem Lyceum (see Rosa, p60, here (and note 43 here).

A memorial by Howard N. Brown appeared in The Unitarian Review 33 (February 1890) here. Includes some interesting passages on this scholar and a student, possessing a wide and varied knowledge of books...

The people were rather proud of his learning, but the farmers who came to hear him had no adequate means for estimating its worth. He was curiously unworldly and ignorant concerning much of the practical business of life. I venture to say that the mowing-machine of one of his parishioners was as much a wonder and a mystery to him as his Greek lexicon would have been in the eyes of the good farmer.

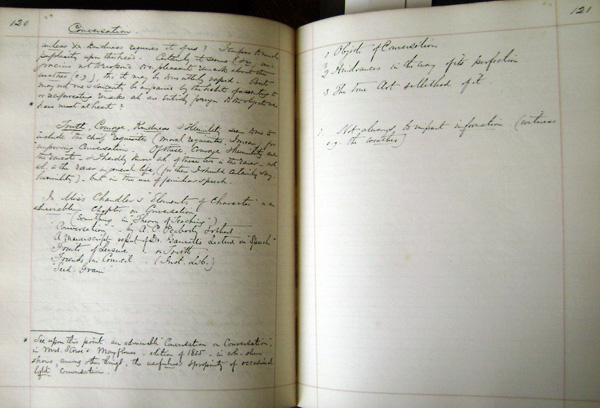

bMS 558 William Silsbee, Theological Common Place Book, 1832 (Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School)

It is a waste of time, to copy passages from authors, whom we may consult as we please. What then is the use of a Common-Place Book? Little or none, for such a purpose. — But if we may always read the passages we deem important, in a printed volume, as well as in our own hand-writing; can we always find the passages we want? No, most truly, as many have experienced to their sorrow and vexation.

Now to aid one in finding such passages, is the simple and benevolent design, of the Theological Common-Place Book.

Its chief use is to consist in its becoming a general index to the passages to which a Theologian may wish to preserve a clue. It is intended, not for a reservoir of mere extracts, but for a reservoir of references. Instead of making a reference, on the blank leaves of a book, where it may be forgotten, or on loose scraps of paper, which may be misplaced or lost; with this volume at hand, one can place it, where it will be safely preserved and always tangible. So far, therefore, will this volume be from consuming time, that it will help greatly to economize it. No one can read systematically and carefully, in a science of such wide extent and uncounted relations as Theology, and not accumulate references. How shall they be laid up, so as to be producible at a moment’s warning, amid a rapid career of thought, and before the vigor gathered and concentrated for the toil of composition, shall (as matter much less ethereal is said to do) make itself wings and fly away? To the faithful and devoted student, who knows the value of time, and the weariness of the flesh

in hunting for authorities, this is a very practical and serious question. To such an one, this volume, it is thought, must supply an important deficiency in the apparatus of study, and, it is hoped, will be found adequate to his wants.

There are also one or two purposes, well worth consideration, which the use of this book may indirectly promote.

It may help a student, gradually to systematize his acquirements. He cannot enter a reference, under a particular head, without recording mentally the bearing and design of the subject which has suggested it, in connexion with some others, — perhaps with many. The habit of observing relations, and impressing them on the mind, is invaluable. It is a tact, to which philosophers have not infrequently owed their eminence.

The mere turning over the pages of this Index, and pausing here and there upon the titles which cover them, will not be without its advantage. It will teach a student, that which, in this era and country, it is so necessary for him to perceive with clearness, and feel with force, — the comprehensiveness of Theology. Young men are sometimes in a hurry to commence the professional labors. When the fit is on them,

let them resort to this long (and it might easily have been longer) Index, and ask themselves, first, how much they know, and next, how much they ought to know, concerning the subjects which its columns suggest.

Cambridge, January 23, 1832.

N.B. In using this Common-Place Book, it will be of no consequence, where an entry respecting any given subject is made. All that is necessary, will be to mark the page, (or pages, if entries be made in more than one place,) opposite the proper caption in the Index.

- John F. Ames, The Mnemosynum : Intended to aid, not only students and professional men, but every other class of citizens, in keeping a record of incidents, facts, &c., in such a manner that they may be recalled at pleasure: with an introduction, showing its benefits and its manner of being kept. Utica, N.Y.: Orren Hutchinson, 1840. A scan of the NYPL copy is here (catalogued under these headings : Memory; Psychology / Cognitive Psychology; Self-Help / Personal Growth / Memory Improvement).

- Susan Miller in Assuming the Positions: Cultural Pedagogy and the Politics of Commonplace Writing (1998) describes a copy used by John Henry Ducachet Wingfield (1833-98), Mss1 W7275 a at the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond.

Images shown with permission from, and thanks to, Manuscripts and Archives,

Andover-Harvard Theological Library, Harvard Divinity School

A. C. Baldwin, pastor, telegraph lexicographer, poet 10 June 2010

N. B. : This entry moved to a separate page under the telegraphic codes heading (today 26 October 2013).

THE INCO N HARD ARE CO. 21 May 2010

Stoddard, William Osborn, Jr. Making good in the village. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1916. Illustrated by George Varian.

N. B. : This entry now under the fiction heading, at Hardware Store Literature.

a system of caring for hardware literature 16 May 2010

Arrangement of Catalogues and Price-Lists

(pp 93-102) in Richard Richardson Williams, Hardware Store Business Methods (1901) moved to hardware store literature page.

W. H. Donaldson, lithographer, codist, publisher 28 March 2010

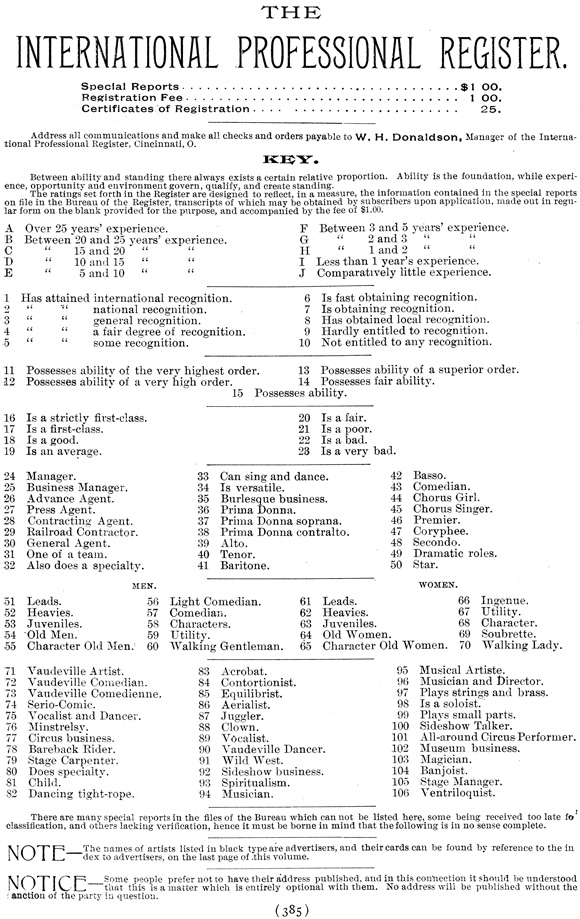

Not a code, but analytical, and evidence of the knowledge of the amusement domain that would support Donaldson’s creation, with a partner, of The Billboard in 1894.

private collection

The Donaldson Guide... to which is added the Complete Code of the Donaldson Cipher.

Cincinnati, Ohio: W. H. Donaldson, 1894

7w x 10 1/2 inches;

theatrical, pp 4-52 of a 418-page compendium entitled, in full :

The Donaldson Guide,

containing a list of all opera-houses in the United States and Canada, together with description of their stages, their seating capacity, and the names of the managers of each; the populations of cities, and the names and populations of adjacent towns to draw from; the names of city bill-posters, baggage expressmen, hotels, boarding-houses, newspapers, vaudeville resorts, museums, beer gardens, fairs, race meetings, circus licenses, and miscellaneous facts, dates, etc., of great value to managers, ¶ in conjunction with

The Showman’s Encyclopedia,

a compilation of information for showmen, performers, agents, and everyone identified with the theatrical, vaudeville, or circus business, such as ticket tables, interest tables, the address of show-printers, costumers, dramatic agents, theatrical architects, scenic artists, aeronauts, playwrights, etc., ¶ and the

International Professional Register,

a directory of the names and address of dramatic people, variety people, minstrel people, freaks, acrobats, operatic artists, musicians, and farce-comedy artists, ¶ to which is added

The Complete Code of the Donaldson Cipher.

More on this code, and Donaldson, here.

the universal baroque 19 January 2010

I’ve long been a casual and amateur fan of emblems. I believe it goes back to Ian Hamilton Finlay’s forays into the genre with his Heroic Emblems, and other of his lapidary experiments with word and picture. I’ve fashioned my own emblems on various occasions, and frequently bring emblems and emblem-making into my teaching. I try to stay current with the literature, at least as manifested in the scholarly journal Emblematica.

In that journal’s volume 17 appeared Michael Bath’s review of Peter Davidson’s The Universal Baroque (Manchester UP, 2007), that led to my reading the book. Before presenting some thoughts on the latter, however, I should provide at least some description of emblems. A few pages in my own website are devoted to the topic, starting here, and from those pages I borrow this sketch —

Emblems were a genre that deployed word and image for rhetorical, ethical and/or educational purposes. Their economy of expression typically took the three-part form of motto, allegorical image and explication, that served to contain their baroque piling-on of detail in a tight, formalist forcefield.

Emblems came into being as a genre with the unauthorized publication in 1531, of Emblematum Liber, which incorporated epigrammatic writing that Andrea Alciato had compiled some years earlier. The Augsburg

edition drove Alciato to prepare a second (and now authorized) edition for publication in Paris in 1534. This incorporated pictures and a different organization, and together with later editions of Alciato, who wrote 212 emblems in all, enjoyed great acceptance. Over 150 editions of Alciati’s collection, alone, appeared over the next century, and something like 2000 emblem books were published in the heyday of the genre. They were used in religious and other education, but also by artists, architects, decorators and others as visual dictionaries or pattern books. The most famous in this regard was probably Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia (1593).

Emblems are open, not closed. The cut-up, paste-up, juxtapositional nature of the emblematic mode lends itself to new occasions of inquiry and meaning. Now back to Davidson’s book.

The Universal Baroque finds in the baroque not a style nor period, but an open system of inclusion, a system of international discourses, a

(1) In Davidson’s baroque, there is no center, no metropolis. Its practitioners might be anywhere and, he finds, are often at their most creative in the margins — Scotland, China, Mexico, Brazil. way of proceeding,

a symbolic language, an agreed set of conventions overriding all of the alegiances of religious confession or nationality which have come to seem, since the turn of the nineteenth century, unavoidable descriptors of all cultural endeavour.The nation state is the enemy of the baroque,

he writes at the start of his chapter on British Baroque.

Davidson derives some of his argument and evidence from Giovanni Careri’s stunning (and stunningly beautiful) Baroques (2002; Princeton UP, 2003), including Careri’s discussion of the mestizo

character of baroque art in the Americas. Davidson takes this up and argues that the baroque is fundamentally mixed, hybrid; it delights in the marvelous and in curiosity, in queer juxtapositions. It takes its selections from both the vernacular and the international, the indigenous and global. It is oriented to antiquities plural, those known and those not yet uncovered. The baroque is an open system that operates with variations. Its practitioners moved between, or within, competing frames of reference.

(85)

He introduces twelve aphoristic theses on the baroque, that are developed throughout the book. A couple of favorites : (1) Baroque art is never at a loss: it has evolved ways of dealing with reality; (2) The Baroque has no metropolis; and (5) The Baroque has reached the last possible point in eclecticism. Each of these and the other theses is followed up by an elaboration, almost in the form of corollaries. For example, to Thesis 1, The baroque system can find an artistic response for any occasion... it need not be original, but it must be accomplished.

(p13)

The largest part of the book is devoted to instances of baroque literature, art, architecture and music in England, Ireland and Scotland, in the New World, and in the East (China, Japan, Goa). It is at the frontiers, Davidson writes, that the baroque arts become more interesting and compelling. There is much about the Jesuits in here. As for England, Davidson shows that much of the evidence is in Latin which, because not in the nation-building tongue, has been expurgated from the canon. (Metaphysical

is a way of having a baroque that is native, unconnected to the continent or anywhere else.) He finds energetic examples of baroque literature in the English, Scottish and Irish diaspora on the continent, and also notes how many Scots doctors of medicine, theologians and jurists sought their education abroad. Davidson’s examples were almost completely unknown to me, and to follow his account required frequent reference to the internet, as well as Careri’s book, and Gauvin Alexander Bailey’s (very readable) Art on the Jesuit Missions in Asia and Latin America, 1542-1773 (1999). Many of my own delicious.com bookmarks tagged baroque are the result of searches triggered by Davidson — Giardino Buonaccorsi east of Macerata, near the Adriatic; the Sedlec Ossuary; the composer Doménico Zípoli (1688-1726).

Why did this book so amaze me? Probably because I like lost or forgotten or marginalized things. Probably because I gather and compile until overwhelmed by my own mess, whose secretary I become. The Universal Baroque came into my view as I was contemplating Umberto Eco’s list

book, and thinking about compilations. The emblematic mind seeks to select and deploy unlike things in a composition: parataxis, hypotaxis, any device that can yield a thought or idea from the congeries, for rhetorical and cognitive purposes. It might be said that (graphic) designers also seek to bring significance out of the chaotic, by classificatory and visual means. And too, I see the baroque in many (not all) of the artists that interest me, including

Ian Kiaer, whose work I became aware of around the time I was reading Davidson.

And more — Davidson draws from Eugenio D’Ors and others to argue for a new map of the baroque world. He would replace that chart in which lines of influence radiate out from European capitals to their colonial holdings, to another that would look much more like a net,

whose nodal points or knots

connect to every other knot, the medium being Latin and the shared visual systems of iconography and emblem ultimately derived from a plurality of antiquities.

(183) As I think about education in the arts, say as discussed by Ken Lum in his Dear Steven

essay in the collection Art School (Propositions for the 21st Century) (MIT Press, 2009), the orientation cannot be solely to the center: What students need to be taught is that art is about making everything in the world relevant.

(339)

I’d encountered another Davidson book years ago, his collaboration with artist Hugh Buchanan entitled The eloquence of shadows : a book of emblems = emblemata nova (Fife : Thirdpart, 1994). Its text (including introduction) is in parallel Latin and English. I’ve shown it to students for 15 years now, as evidence that the emblem form remains alive even in our day.

index rerum 1 January 2010

For Material Cultures 2010, Edinburgh, this proposal has been accepted under the heading readers and reading practices

—

Indexing as autobiographical practice in the 19th century :

an examination of copies of John Todd’s Index Rerum

John Todd’s Index Rerum (1833, and much reprinted) was a personal database system designed to facilitate indexing of all the reading done by the student and the professional man.

The system was borrowed from John Locke’s own. Key (index) words would be entered on the page whose two letters at the top — the first for a word’s initial, the second for the first vowel following that initial — matched that word. As a one-volume index to many volumes, Todd’s Index Rerum was obviously suited to the needs of ministers, lawyers, and physicians, among others. It was widely used.

And yet only two of the eight copies that I have closely examined used the book exclusively for its designated indexing purpose. Instead, we find short and lengthy extracts; personal resolutions; diaries; pressed flowers; autographs; ready reckoner

data and computations for mill and other engineering work; drafts of (unsent?) letters; a personal memoir. We find multiple users, in cases where a daughter or widow takes over the unused or lightly-used book of father or late husband. We find experiments in writing one’s signature. We find receipts, drafts of poetry, and other matter loosely inserted.

How are these various practices — all captured in these Index Rerum — to be understood? This small sampling represents only a tiny reading experience database,

but the reading is woven in with other practices. Taken together, I argue, these activities were instrumental in developing and maintaining a personal identity, one that indexing helped assure was connected to a larger intellectual milieu.

My reading takes into account critical contemporary views of Todd’s Index Rerum (there were competing systems, of course), and is informed in part by recent scholarship on what may be its closest analogue, zibaldoni (copybooks) of Renaissance Italy.

Reference: some scans, transcriptions and ongoing analysis of these copies is presented here.

telegraphic brevity 2 October 2009

from Notes and Queries, 5th series, volume 10, 28 December 1878 —

Telegraphic Brevity. — The art of concisely expressing ideas is worthy of acquisition by all who write for the press. But the Queen has gone ahead of them all by her pithy telegram sent to Princess Louise from Windsor Castle, December 1, Delighted at reception. Say so.

On this text a man writes in the New York Sun:—

Were there a medal or chromo on offer for the tersest comprehensive telegram, Queen Victoria would probably win it by her Sunday’s

John E. Norcross. Brooklyn, U.S.

Delighted at reception. Say so.

This despatch quite surpasses in compactness Caesar’s famous Veni, vidi, vici, since two-thirds of that was plainly surplusage, vici being all that was required. When cable despatches are paid for word by word, to combine fulness and brevity in them is a triumph of economy; and to transmit fully and fairly the Queen’s two distinct burdens of information and command in fewer than five words would puzzle most people. At all events, to exceed this royal brevity without sacrificing sense or sound would occupy an amount of time (which is money) that might cease to make success economical. Had the Queen and her daughter been experts in the tongue of the former’s great-grandfather, she might have accumulated into one formidable German polysyllable, several inches long, the latest domestic or political news; but, using only the Queen’s English, as she did, we think her clearly entitled to the championship.

A Boston Transcript article looks for further economy in the Queen’s despatch —

The Queen’s dispatch to the Princess Louise is pronounced extravagant, the last two words being superfluous, since the Princess would certainly

Say so,

and the second and third being equally unnecessary, since the reception was the only thing at which the Queen could have been delighted. Moreover, the dispatch should have been sent at night rates, and the Queen by neglecting to be economical has set a bad example to Canada and its new rulers.

It would appear, however, that the Princess did not say so,

hence the Queen’s instruction.

on dotting the i’s and crossing the t’s 13 August 2009

One encounters variants of this expression in the introductions of early telegraphic codes. Thus :Be extremely cautious in writing the words in a plain hand to the dotting of i’s and the crossing of t’s. Invariably write the T at the beginning of a word thus,John Wills, his Electro-magnetic telegraph vocabulary, or, Condensing correspondent, designed to communicate commercial and other general intelligence, in abbreviated form and at small expense (Baltimore, 1846),T,as printed, or thust,to prevent the operator mistaking it for an F. Use no hyphens.

and In sending messages in cypher, write each word legibly. Begin each word with a capital letter, be sure to dot the

in George W. Phillips, his Telegraphic cypher for transmitting commercial intelligence, &c. by telegraph or otherwise (Third edition, revised and corrected, Cincinnati, 1860).

i’s

and cross the t’s

and no mistake can occur,

In telegraphic communication, one codeword might unpack into a sentence-length’s intelligence. A clerk’s or operator’s misreading could occasion a failed transaction, even significant loss. Nor would there have been much context to help; nor was much redundancy built into these early codes, as there would be subsequently. (Though Wills provided figures and letters — indicating columns and rows in a table, respectively — to follow codewords, where usage warranted. Example: the codeword Drumming

might also be expressed as Drumming—3—U

.)

telegraphic swimming meets 20 July 2009

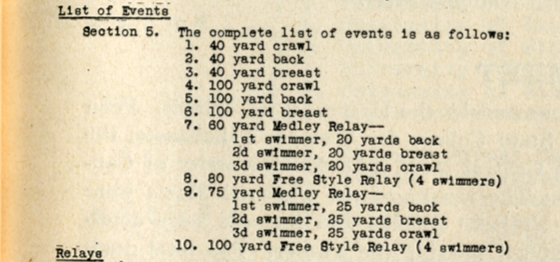

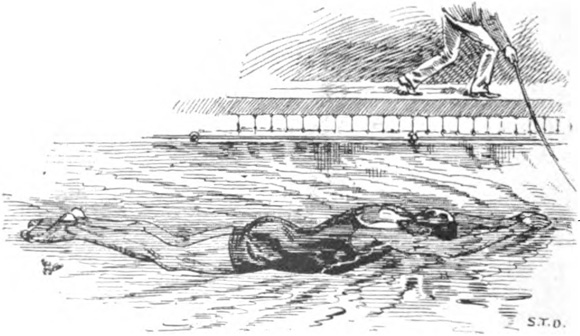

My younger son is a swimmer. I swim and am absorbed by telegraphy. When Spalding’s 1935 Athletic Library handbook containing rules for National Telegraphic Meets came my way, I was interested. What were these?

overview

official rules, 1936

a future for the telegraphic swimming meet?

The Plunge

sources