putterings 455a < 455b > 455c index

Joseph G. Robin; some transcriptions (contemporary profiles, and a letter)

in progress (20240826)

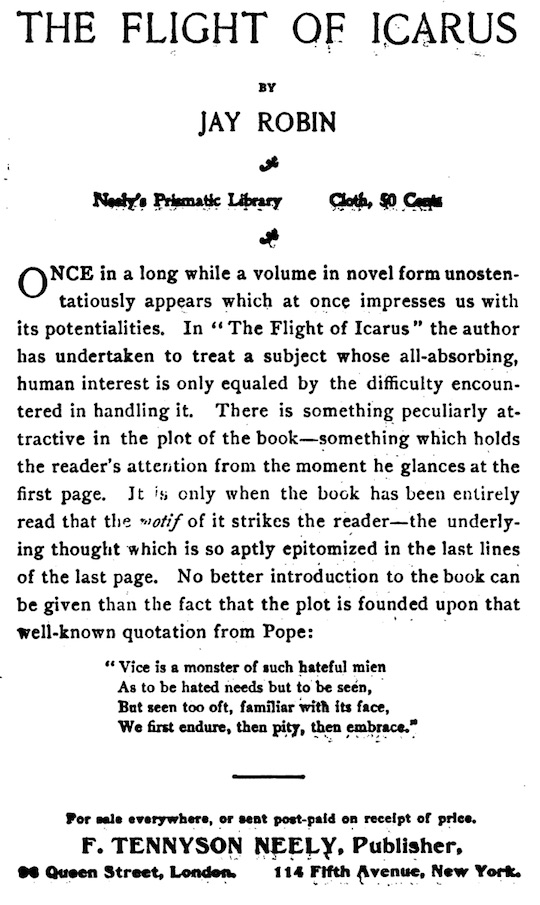

- publisher's display advertisement for The Flight of Icarus (by “Jay Robin”)

- review of The Flight of Icarus (by “Jay Robin”) in The Medico-Legal Journal (1899)

- “Began on a Shoe-string” (NYTimes profile; December 28, 1910)

- “Banker Robin Scoffs at Aged Couple” (Rocky Mountain News; January 6, 1911)

- “Millions from Nothing; New York’s frenzied financier” (Rocky Mountain News; January 11, 1911)

- “Sentenced to Serve Year in Penitentiary” (The Bridgeport Evening Farmer (January 10, 1913)

- “A ‘Go-Getter’ World” (Odin Gregory, letter to editor, New York Evening Post; August 2, 1924)

paragraphs numbered for ease of reference (and proofing)

▌ bar at left returns to top of page.

![]()

1

publisher's advertisement,

in back of Louise F. Suddick, Zerelda: A Story of Love and Death (1899) : link

![]()

2

review of The Flight of Icarus. By Jay Robin. F. Tennyson Neely, New York, Publisher. 1899

The Medico-Legal Journal 17:1 (1899) : 150-151

Harvard copy/scan (via google books) : link

- Mr. Robin has certainly not made a dead failure in his first book, for it has enough of human interest to make even a busy man read it through when he takes it in hand. You cannot say this of many of the first productions of even the literary successes of the world.

- Mr. Robin need not write a novel to show that a successful novel should be logical as to its representation of human action.

- We would have to search long to find an established work of fiction that could be called logical. The highest style of fiction, as it seems to me, are works like the Arabian Nights entertainments, Dumas’ Monte Christo, and Cervantes’ wondrous tales of the Knight of the Sorrowful Countenance.

- Robin’s work is rather a study of the Psychology of Love, as a passion, than anything else. It is not a work of fiction.

- When we study the actual facts of vice, and its contact with human emotions and passions, and grope after the truth, as it really is, no matter how much it is stained by sin, or colored by its peculiar environment, our research possesses human interest.

- It is problematical, if not doubtfully rare, if the Reveres of this life can wade through so much mud, as did the hero, with so little slime left sticking to his garments.

- Reveres’ punishment of Perry is one of the best chapters of the book. The journalistic portraits are doubtless studies from the author’s note book, and some of them splendidly done. But the sea of life, like the shores of the Rhine, are full of such shipwrecks, and it has its Lurlei, its Syrens, and its catastrophes.

![]()

3

“Bank Owner Began on a Shoe-string; With less than $500 Robin, born Robinovitch, bought a million-dollar company; Then sold out at a profit; Got into real estate and presently had his own chain of banks — Career began with selling a scandal”

The New York Times (December 28, 1910) : 2

link (pay-walled)

- Joseph G. Robin, whose operations have resulted in the closing of a chain of small banks, involving a traction company, several real estate concerns, and at least one other financial institution, has had a remarkable career. He is not more than 37 years old and was only 10 years old when he came here from Russia. His family is said to have been expelled for political reasons, but of this there is no proof.

- He settled in an east side Russian community, and grew up there with his sister, Louise G. Robinovitch. She became a nurse in one of the Blackwell’s Island hospitals and later graduated in medicine and held a post in the Manhattan State Hospital for the Insane on Ward’s Island.

- The first interest Robinovitch — who later by permission of the court became Robin — began to take in affairs outside of his own circle, so far as is known, as [sic] was manifested about 1893 when he sold to a newspaper the facts about a scandalous condition of affairs in the city hospital in which his sister was employed. He had previously been an east side reporter on the old Recorder, and for a short time after the sale of his hospital scandal story was employed by the newspaper which purchased it.

- With the money, about $300, paid to him for this information and his own savings, probably less than $500 all told, he found himself in Buffalo one day before 1895. He heard some one say casually that one of the big electric companies, which used the Niagara water power, was for sale. Immediately he went to the office of the company and began negotiations for its purchase. It is said that he completed the deal for a million-dollar company on $500, getting his option, and then raising the money with which to make the first payment for control. Later he had no trouble in selling out at a large profit.

- With the capital thus obtained he set out in the real estate business. He even initiated a small savings bank and became interested in various building and loan associations. About this time he decided that his name was a disadvantage to him, and got the court to let him shorten it to Robin. From that time forth he let it be known, it is said, that he was a Frenchman. He wore a beard after the French manner, and his office manager, Theodore Werner, said last night he had known him seven years and had always been told he was a Frenchman. He had never heard that Robin’s name had been changed.

- Robin’s active financial career in New York began about 1896 with several building and loan associations, most of which were only fairly successful. Later he helped to organize the Co-operative Building Bank, of which Timothy L. Woodruff was General Manager. This institution was later backed by the Merchants’ Exchange Bank and is still going.

- In 1904 he organized the Bankers’ Realty and Security Company, which invested heavily in Bronx real estate, and is one of the concerns of which he is still said to hold control. About this time also be became a factor in the management of the Washington Savings Bank, of which he is still president. His connection with this bank led to his becoming interested, with the Heinzes and with E. R. and O. F. Thomas, in the Riverside Bank, thus making it possible for him, in the merger two years ago, to become the ative executive head, though not in name, of the Norther Bank. A year ago he was rated as being worth $1,000.000.

- Supt. Macdonald of the State Insurance Department of Connecticut said yesterday that, after Robin obtained control of the Aetna Indemnity Company, when F. Augustus Heinze had apparently been eliminated after tha panic of 1907, Mr. Macdonald had continually to keep after the company to get it to hold securities of which he could approve. At one time it held 200 Northern Bank shares, but he made it sell them. Another time the company held on $40,000 mortgage on Robbin’s house on Long Island, but this also the Superintendent considered to be improper and it was taken out of the company.

- The stock of the company was at one time reduced from $350,000 to $250,000, but Mr. Macdonald insisted that it be raised again to its original figure. Last March negotiations were nearly completed for the sale fo the company to the Commercial Union Company, but they fell through. At this time new officials were elected. It is now alleged that these officals have merely done Robin’s bidding.

- Dr. Louise Robinovitch, sister of the meteoric high financier, has herself acquired some celebrity. A year ago she made some startling assertions as to the power of electricity in producing what she called “electric sleep.” She asserted that in the laboratory of the Hospital of Sainte Anne in Paris she had put a dog into this electric sleep three times and each time had revived him, although to all ostensible purposes the electric sleep was the equivalent of death. The animal’s heart, she said, had ceased to beat and all the functions of nature had stopped, but she applied artificial respiration by means of electricity, and in a few minutes the dog came back to consciousness and life as though nothing had happened.

- She has since applied the same methods, Dr. Robinovitch asserted, in the case of human beings, and had restored by electricity a man who had completely lost power over his right side.

- Still more marvelous were her reports about a certain woman victim of the morphine habit. She was apparently dead in Sainte Anne’s Hospital in Paris, said Dr. Robinovitch, and for twenty minutes after the last beat of her heart had been recorded physicians had vainly tried to revive her by artificial respiration. They she applied her electrical methos and the woman revived. From this she argued that in certain cases of apparent death there was no reason to give up hope. If there was no definite lesion of the heart or respiraitory organs, and the patient was only suffering from the effects of chloroform, morphine, strychnine, drowning, or electric shock, rhythmic excitations by electricity would once more restore the normal functions of life and the patient would recover.

Robin rushed to Sanitarium.

His sister has him committed after he had tried suicide. - Joseph G. Robin was rushed to a private sanitarium on an order obtained on a holiday from a Supreme Court Justice at his home.

- According to Robin’s friends, he had been in breaking mental and physical condition for more than a week. He evidently saw, they said, that trouble was coming for his enterprises, and this, added an aggravated case of gallstones, brought him to his bed in the Beaux Arts apartments, Fortieth Street and Sixth Avenue, and in the end, according to friends, to at least one attempt to commit suicide.

- The application for commitment papers to send Robin to a sanitarium was made by his sister and next of kin, Dr. Louise G. Robinovitch, after he had tried to throw himself from a window of the apartment on last Saturday night. He had reached the window, so James M. Clifford, his lawyer and associate in several directorates, said, when a watchful nurse intercepted and held him until help came.

- He had been under the observation of alienists such as Dr. Carlos F. MacDonald, Dr. Wildman, and Dr. Schrapp before this, it is said, and after further examination of him on Sunday and Monday they decided to report that he was suffering from acute paranoia, and recommend his commitment. Their report was made to Supreme Court Justice Amend at his home, 38 West Ninety-fourth Street, on Monday, and Justice Amend signed the papers. Before the ink was hardly dry Robin was on his way to Dr. MacDonald’s sanitarium in Central Valley, N. Y., for an indefinite stay.

![]()

4

“Banker Robin Scoffs at Aged Couple Who Call Him Son;

Old Folks Mourn With Grief as He Turns Back; Tangle Hurried Lexow’s Death.”

The Rocky Mountain News 52:6 (January 6, 1911) : 12

via Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection : link

- “What’s the matter with you anyway? What do you think you’re trying to do?” asked Joseph G. Robin, the fallen banker, today of the gray-headed couple who say they are his parents.

- Annoyed, ill at ease, by turns smiling and scowling, he refused to have anything to do with them, or even to admit that his parents were in this country. In his denials, his sister. Dr. Louis Robinovitch, who has been constantly beside him, took a similar firm stand. In Brooklyn a newspaper reporter found a humble old pair named Rabinovitch who thought Robin might be their son. Detectives brought them to the criminal courts building today, questioned them about their family history and then arranged to have them meet Robin.

- “No,” said he, “I don’t want to see them, and nobody can make me. They’re nothing to me.” So it was necessary to lead him to the district attorney’s office with assurances that he need answer only a few questions. Once there Mr. and Mrs. Herman Rabinovitch were brought into the room. The woman had the quicker eyes.

- “My son! My son!” she cried, half in Yiddish, half in English. “This is my son,” and made as if to embrace him. Robin smiled and turned his shoulder. “Ask him if he is not my son,” she protested to the district attorney. It was then that Robin startled the room with his abrupt question. The woman, who says she is his mother, shrank as if she had been struck and broke out in lamentations. Her husband, whose sight is not of the best, and who understands no English, had been peering anxiously at Robin. The old man took a step closer, looked him narrowly between the eyes and affirmed positively:

- “This is my son. I know him.”

- Again Robin denied that his parents were in this country, and at this fresh denial the husband joined with the wife in upraised hands and moans of grief that could be heard through the outer corridors. Alienists for the state noted each gesture and expression of Robin.

- The sister met similar affirmations with similar denials.

- “I probably” have seen these old people in Brooklyn," she said, “but I do not know them. My brother’s parents and mine are in Russia.”

- Previous to the confrontation, neither of the two pairs knew that the other was in the building. Robin’s answers to questions gave the same birthplace and the same names of sisters and brothers, with one exception, as those given by Mr. and Mrs. Herman Rabinovitch.

- A mental examination of the prisoner was concluded today by alienists for the state but their finding was withheld.

- The grand jury today, it is reported, ordered six additional indictments against Robin, charging him with grand larceny to the amount of $200,000 from the Northern bank and the Washington Savings bank.

- District Attorney Whitman said today he had been told that Clarence K. Lexow, who was counsel for Robin, had worried himself to death over the tangles into which Robin became involved. Former Senator Lexow died at his home in Nyack last Tuesday.

![]()

5

“Pen Sketches of World Celebrities;

Millions from Nothing

Story of Robin, New York’s frenzied financier, who disowned his parents.”

The Rocky Mountain News 52:11 (January 11, 1911) : 12

from Kansas City Star

via Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection : link

- THREE o’clock in the morning. In the tapestried halls of Driftwood Manor (cost, $500,000), near New York, the overturned glasses on the table, the melting ice in the silver champagne buckets, the rumpled napkins and the tired faces of the servants told the story of the night. All the guests had gone, all except one. She had lingered.

- “The train,” she exclaimed, “the train, I shall miss it.” The man sprang to the wall and touched a button. Within a moment a motor car was chugging in front of the great steps which led to the manor, a be-furred woman hurried into the limousine and the start, with the man, was made. Risks made no difference to the driver of the car and the start hardly had been made, it seemed, before the station appeared, framed in the circle of the motor’s lights.

- The station agent didn’t appear a bit worried. Yes, the train had gone — just five minutes ago. But there’d be another in an hour. An hour. It didn’t seem long to the station agent, but it did to the woman. Her host jumped to a telephone and asked for hurried connections with the general offices of the Long Island Railroad.

- “This is Robin,” he said, when the telephone rang again, “Joseph G. Robin, the banker. One of my guests has missed her train to the city. Send me a special train. Yes, I know about that, but I don’t want to wait. I want a special train. Huh! never mind the cost.”

- And perhaps that helps to explain why Joseph G. Robin now stands accused of wrecking the Northern Bank of New York and of the Washington Savings Bank of New York. So far he is shy $280,000 and the books are being gone over.

- SIXTEEN years ago the steerage of a steamer from Russia gave forth four persons who were listed as Herman Rabinovitch. wife, son and daughter. Gradually the son and daughter drifted away from the parents. The daughter became a physician. Dr. Louise Rabinovitch. The son became Joseph G. Robin, rated in 1903 as worth $1,000,000 and rated now, according to himself, as “with-out a penny in the world.” It is said the daughter still remembers her mother and father and sends them money occasionally. The son’s memory is not so good.

- It was in the New York district attorney’s office the other day that an old man and woman sat waiting. A young man entered. The man and the woman started forward.

- “Josef,” the old man exclaimed, "Josef! Don’t you know me? Ach. Gott, don’t you know me?”

- The young man turned and smiled, then laughed.

- “You?” he questioned, “who are you?”

- “Josef!” came the reproach, “you know me, Josef!”

- The young man cursed.

- The denials could not last. Questions from the district attorney brought from the indicted man the admission that the man and the woman who confronted him had brought him to this country sixteen years ago.

- “But they’re not my father and mother,” he said; “they’re just friends of the family. You see, they brought me to this country, and after awhile, I left them and started out for myself. That is all there is to it.”

“He is our boy.”

- But the older woman and the older man would consent to no such story. He was their son. they said, a son who had forgotten them, who had neglected them in times of need, but still their son. But Robin had regained his composure and questions only brought laughter.

- THE fortune which Robin built, in the years he was forgetting; the days he spent in the steerage, was built out of nothing. From one small deal to another he got enough money to go into the building and loan business. But the business was not profitable. He soon was “broke” again. Just how wildcat financiers can make the acquaintances that will enable them to do their work is something that’s a hard matter to fathom, but just the same they make those friends, and it was such friends that enabled Robin to do his work.

- When the receivership of the Hamilton bank came to an end in New York in 1907, Robin, through his friends, was put in a position to bid for the stock. He obtained a controlling share, with the promise that he would pay the money within a year. He also promised to have $1,000,000 dollars ready to pay depositors on the opening day of the bank. Instead, bank loans had come due in the time of the receivership and were collected by Robin. When the bank opened it paid the depositors with its own money and Robin thus practically was given the controlling interest in the bank, for he had not put up a dollar. The payments on the stock, also, were made out of the bank’s income.

- WITH the start the Hamilton bank had given him, Robin began to acquire others. The Riverside bank whs obtained through practically the same methods through Charles W. Morse, and in it, like in the Hamilton bank, Robin threw out the old officers and placed in others of his own selection. The Northern bank and the Hamilton were consolidated. Soon, with the aid of the Washington bank, acquired “easily,” Robin owned a chain of banks with total deposits of $7,000,000.

- When a man has $7,000,000 practically under his direct control, there’s a mighty strong temptation for him to do things other than he should with it. And evidently Robin was not averse to the temptation. There was real estate to dabble in, there was a chance to build an interurban line, which, if it did not do much business, certainly would be a convenience when he needed it. Then, too, there were loans to be made on his own property. According to the charges brought against Robin, he did everything that one would do when the temptations “take.”

- The interurban railroad is in the hands of a receiver, the loans have been found out, the authorities are tracking down every financial move of the banker, and the grand jury has been piling up indictments. Did the usual woman in the case have anything to do with it? A whole lot, but in this case the noun must be used in the plural. Robin loved Broadway, with its lights and its high-heeled girls, and Robin loved not sagely, but with an over-abundance of affection and an over-energy in the art of spending money to foolish purposes.

- THE banker’s assertion that be isn’t worth a cent is exactly true — according to those who have investigated him. Technically, it may be. Really and truly, Banker Robin, while, in jail, still is a rich man. For out in Suffolk county, Riverhead, Long Island, is a great mansion, built at a cost of nearly $500,000, which still knows Joseph G. Robin as its head and master, although a document recorded with the county clerk transfers the property to Dr. Louise Robinovitch, his sister. That is Driftwood Manor.

- The story of Driftwood Manor is a story of high living, extravagance and wine parties attended by Broadway chorus girls and New York politicians. But although the country around knew of them, the inhabitants of that country could never gaze into a window nor spy a glance into the doings of the “manor.” Robin attended to that little matter when he built the place.

“Chorus girls at the manor.”

- It was in 1907, shortly after he had acquired the Hamilton bank in New York for nothing, that Robin bought the acres of land upon which the manor was built. But he didn’t buy it in his own name. Instead, the Wading River Real Estate company was hurriedly organized for one purpose, and that purpose was fulfilled when the deed to the property changed hands. The cost of the 112 acres was $12,000. It was merely a small item of the expense. The house, built of concrete, cost $125.000. The outbuildings cost $40,000, but again the limit of expense was not reached. There was the interior furnishings to be done, and in this Robin spent a fortune. Europe gave up expensive tapestries, furniture and decorations. And there was a final expense of $500,000 for all of it. The house stands half a mile from the highway. Robin wanted more privacy; he called for a great gang of shovelers. Their task was to erect a series of mounds that would extend around the entire place with the exception of the solid gates that were guarded. And in this manner the parties which many times lasted all night were kept a secret.

- IT was not until the insurance department of the state of New York became active in its investigations of the Aetna Indemnity company, in which Robin was a controlling factor, that the wreckage began to pile up. Then, when the investigators learned of all the apparent irregularities, Robin fled. He was arrested and on the way to court he attempted suicide by taking hyoscine, the drug which killed Belle Elmore, for whose death Doctor Crippen was hanged in London. The drug did not do the work that had been planned for it, however, and a few days ago Robin was taken Into court again, when he pleaded not guilty. His sister says that he is insane and that he is an habitual user of morphine because of bodily pains. The court, however, is to determine whether his insanity is of the kind that really exists, or whether it is of that nature that comes in handy when one is in trouble.

- The stanchest friend of all in Robin’s trouble is that sister. It was she who aided him in eluding the officers when the crash came which called for his arrest, and it is she who says she can prove to the court and to everyone else that her brother has been insane for years.

- Delusions, the sister says, have affected the brother for years. Many times she has had to take precautions to protect his life, because he believed that persons associated with J. Pierpont Morgan and the Pennsylvania railroad were seeking to kill him. He spoke of these fears often. Doctor Robinovitch says.

- Robin, in jail, is contrite and remorseful — save on one point and in that he is firm as a rock — he won’t acknowledge the Robinovitches, who claim him as a son.

![]()

6

“Sentenced to Serve Year in Penitentiary

Robin, Pleading Guilty to Theft of $127,000 From Bank, Gets Off Easy

Clemency shown for aiding in conviction of Cummims [sic], Reichman and Hyde”

The Bridgeport Evening Farmer (January 10, 1913) : 12

LoC’s Chronicling America : link

- New York, Jan. 10 — Joseph G. Robin, noted financier, who pleaded guilty to the theft of $127,000 from the Washington Savings bank, today was sentenced by Justice Seabury to serve a year in the penitentiary on Blackwell’s Island.

- Robin was given clemency because he had aided the district attorney i securing the conviction of William J. Cummins, Joseph G. Reichman and former City Chamberlain Charles H. Hyde. Following the collapse of the Northern Babk and the allied institutions, including the Washington Savings Bank, Robin was arrested. It was stated by the district attorney that he had stolen more than half a million dollars which he had used in pyramiding operations along the line made famous by Charles W. Morse [1856-1933, wikipedia].

- Robin was declared insane but later he sent for the district attorney and told him that he was in a position to convict Cummins and Reichman, who were the responsible officials of the defunct Carnegie Trust Co. Whitman agreed to use Robin and the latter entered a plea of guilty to the indictment charging larceny from the Washington Savings Bank. This was a year ago and he has been held in the Tombs and was later star witness at the Hyde, Reichman and Cummins trials. It was said that there was an agreement that he was to be given freedom and State Superintendent of Banks George Van Tuyl sent an open letter to Justice Seabury demanding the limit of the law for Robin because he said he was one of the most defiant lawbreakers he had ever known.

- But despite this demand, the court, today, said the penitentiary sentence of one year was sufficient.

- The rise of Robin from a penniless immigrant boy to a potential figure in the world of finance in this city is one of the most remarkable business romances ever written. Starting as an office boy down town, he manipulated small sums in various deals until he finally got a minority interest in the Northern Bank. Then he branched out until at the time of the collapse of the Northern he was a director or executive official in a dozen banks, two realty companies and one big development company was counted as worth ten million dollars.

- His father and mother — at least they claimed they were but he and his sister, Dr. Louise Rabinovitch, combatted the contention — suffered for the lack of food during recent years and were disowned and cast off by the banker. They recently died in abject povery and the manner in which Robin — he had legally changed his name — publicly repudiated them although admitting they brought him and his sister from Russia and kept them until they were able to care for themselves, resulted in Robin being criticised.

- A report widely circulated and generally credited that Robin had made nearly a million dollars since he was first arrested, was denied by Robin. He personally appealed to the court for clemency. He insisted that he was really innocent of the charge to which he pleaded guilty and in an indirect manner attempted to have the plea set aside so that he might go to trial. But District Attorney Whitman told Justice Seabury that he had no doubt of Robin’s guilt.

- “This defendant promised the state that he would be of inestimable benefit to it in other prosecutions and he made good his word,” said Whitman. “He is deserving of consideration for that alone.”

- Justice Seabury said that he could not consider any suspension of sentence. He said there was no doubt of Robin’s guilt but said:

- “Taking into consideration that you have been in the Tombs 22 months the court will make the sentence as light as is consistent with the ends of justice.”

- He then sentenced the banker to one year in the Blackwell’s Island penitentiary.

![]()

7

“A ‘Go-Getter’ World,”

being a letter to the editor by Odin Gregory, in response to a review (unseen so far) by J. Ranken Towse, in

the New York Evening Post (August 2, 1924) : 941

NYS Historic Newspapers : link

- To the Editor of The Literary Review:

- Sir — Never before have I written to the editor. The thought of doing so makes me feel awkward. Also, it embarrasses me, because I appreciate the kind things Mr. J. Ranken Towse has said of some parts of my work. So these presents to you only because of the following sentence, in his review of “Jesus”:

- “It smacks strongly of anti-Semitic prejudice and is especially virulent against the God of the Old Testament, whom it identifies with Baal”

- Please, may I be heard?

- Why “anti” anything? Why “prejudiced”? If one labors to paint his conception of a fair face does he thereby set himself down as being “anti” all dark skins?

- In “Jesus” I have tried to picture, as I understand them, the motives and actions of the Jews in Jerusalem in or about A. D. 30. If the motives and actions of Catholics, Presbyterians, Luterans, Methodists and so on everywhere in A. D. 1924 are precisely the same, does my stating the fact may be anti the reputed chosen ones of Exodus?

- If people who call themselves “Christian” find that they have to apologize for the ethics advocated by their God, if they find they have to gloss over this and to treat as only a poetic figure, or a parable, the other, of the plain teachings of the Founder of their “faith,” and if, in the end, they find themselves compelled to dismiss as impractical all of his moral admonitions that touch the back, the fist, or the purse, may not the noising abroad of this intelligence be claimed as much as anything else to be a justification of those who had the courage to cry to Pilate: “Crucify Him?”

- Truly, disregarding the imbecilities of the mumbo-jumbo, what is there substantial that differentiates the “Christian” motives and actions of today from the Jewish motives and actions of the first century of our era? Truly, who will assert that the whole “civilized” world is not at this moment entirely Jewish in inspiration and in performance? Truly, who will retute the justice of my three lines:

“You vassals of the sneering, knowing Jew,

Who laughs to hear you mumble ‘Jesus!’ ‘Jesus!’

The while cadavers lift you to crafted heights.” - Existence presents itself to us as a struggle, a fight. Tissue grows from the digesting of other tissue. Something physical must cease to be in its form that another thing physical may take form. What, then? After all, may it not be that the virile philosoph of the bull-god is the true cosmic philosophy? After all, may it not be that the right way of life is that of force, of cunning, of guile, of the overcoming of the weak by the strong, by whatever menas? Is that what we really believe? If it is, why lie about it to ourselves, or one to the other? Why not play the game. Why not acknowledge openly the supreme godship of the very practical Baal Jehovah? Why not replace the piteous cross with the awesome horn that curved from the corners of the Israelitish high altar?

- Please, Mr. Editor, and please, Mr. Towse, look at the world about you, and answer me sincerely: Is it anti-Semitism to publish the triumph of the God of strength-in-war over the God of non-resistance, of the God of eye-for-eye over the God of turn-the-other-cheek, of the God of get-and-keep over the God of sell-and-give-away, of the God of build-me-a-temple over the God of pray-in-your-closet, in short of Jehovah the God of the Jews, over Jesus, — well, — the what?

- Verily, so far from its being anti-Semitism, is not the pointing out of this mighty victory rather a call for Knight of Columbus and Ku-Kluxer, for Bishop and Deacon, for Commandery Templar and New York Athletic Clubber, yea, even for His Thrice-Nordic Puissance, Henry of the Flivvers, to show the fine sporting spirit, to pass over the not unadjustable details of beards and baths, of noisiness and noses, to bow head and knee in homage, and dutifully to kiss the odorous gaberdine of Galician Abraham Isaac Jacob Cohen, arch protagonist and highest exponent of all the things that a “go-getter” world holds to be really sane, worth-while, and desirable?

- “Dammit,” exclaimed a man of my acquaintance who wore a Sam Brown belt effectively in 1918, and who is now doing very well in the bond business: “You’ve as much as said that we’re all Jews — all of us!”

- “While you are —?”

- “A Christian, dammit — a Christian for a thousand years back!”

- “Which means — ”

- “That I am a Christian, — a — a —”

- “A non-taker of usury, a forgiver of trespasses against you, a turner of the other cheek, a non-accumulator of wealth —”

- “Hell! That’s silly!”

- I put it to you: Is there just cause for the most passionate Semite-Zionist taking exception to my lines:

“You vassals of the sneering, knowing Jew,

Who laughs to hear you mumble ‘Jesus!’ ‘Jesus!’

The while cadavers lift you to crafted heights.” - Good my masters; I think you.

Odin Gregory,

New York.

[Note by Mr. Towse]

Mr. Gregory seems to be laboring under the strange delusion that Christian morality is founded principally upon the Old Testament. The reference to anti-Semitic prejudice in my review was prompted solely by his virulent delineation of Jewish character. His letter is its own sufficient answer.

26 August 2024