putterings 550 < 550a > 551 index

Elise M. Rushfeldt. “Over Grandmother’s Patchwork Quilt; Wherein Patsy’s Troublesome Question Is Answered”

The Farmer’s Wife 33:5 (St. Paul, Minnesota; May 1930)

Minnesota (Historical Society) Digital Newspaper Hub : 9, 36, 37

transcription, based on OCR text, below.

▌ bar at left returns to top of page.

“Parkhouse” — possibly Herbert Stanley Parkhouse (1903-56), known for magazine and advertising work, some nudes, and later, work in Hollywood.

image cropped from scan, and considerably lightened (levels 0 3.00 255).

![]()

- “Patricia,” called Mother Brunhilde from the wide cool porch that rounded the front and the side of the large, white farmhouse. In her arms, and partly dragging the floor of the porch, was a cheerful log cabin quilt of silks in a harmonious color medley.

- She saw her on the other side of the Japanese barberry hedge by the tennis court, a pretty childish girl, her slender figure a windblown silhouette against the green. She stood at the entrance of life’s forest, thought Mother Brunhilde, and many paths tantalized her to follow.

- Near her was Mother Brunhilde’s son, Martin, slow-moving and sturdy, with the homely, likeable face, as slow of speech as he was cool-headed and reliable.

- Suddenly Patricia’s voice cut across the green lawn space. “A flapper? Perhaps I am. A flapper wants life. And what have you to offer here? What can a farm give of life except monotony? Really, Martin, I’d like to know?”

- “In this case it offers myself.” That was all of his simple argument.

- "But I’d rather have you and the town both. Then perhaps it would be yes —”

- “Um,” murmured Mother Brunhilde, moving to a southern exposure of the porch where the wind could not carry the sounds. Her thoughts raced back to the time when she had been as slender and girlish as Patsy, when she had had the same insatiable desire for life — and it had carried her to this midwestern peaceful farm.

- So Patsy thought life meant a town, did she? Recently Martin had been talking of leaving his farm, the farmstead adjoining this one, and moving into town. But in town Martin, as a salaried man working for someone else, would not be the same. He was a born farmer with a liking for the soil and growing things, and all his training, both at the Agricultural College and here had centered in farming. Grandmother looked over the hedge and through the arches of the grove of trees over great rolling stretches of grain, flowing peacefully on to a shining silvery lake, tree-rimmed, caught in a valley cup. Near the lake was Martin’s farm. They had deeded it to him, this part of the original homestead.

- What could a farm offer of life, indeed? She could but know the cup that had been given her to drink. Patsy’s potion would be partly of her own brewing.

- “It took me an age, didn’t it, Mother Bee?” Patricia, very slim and fair, her shining hair pulled into a loose knot at the nape of her neck, and her face somewhat flushed, stood by the porch railing.

- “An epoch,” smiled Mother Brunhilde, arising from the apple-green porch rocker — she had painted it herself. “The log cabin is ready to be tied, and you said that you wanted to tie it with me.”

- She gathered the quilt into her arms. Patricia’s eyes followed her erect, ample figure. Her grey hair was naturally wavy, her eyes keen, even without glasses, her teeth, somewhat dentist-patched, it is true, were, nevertheless, strong and her own. The cool black and white voile, with touches of red embroidery on collar and cuffs, suited her. She dressed for her John, the ruddy-faced beaming Viking, her husband.

- “I told Helga to put the quilting frames in the dining room,” she said, as she moved toward the sunny east room with its wide bay windows looking over the grassy slopes of the farm lawn, tree and shrubbery studded.

- Mother Brunhilde could well have afforded to have stocked the place with new walnut period furniture, Wilton or even Oriental rugs, and the latest flair in readymade articles, and then to have had a number of maids to keep them in order. Instead she preferred simplicity and handwork. Every winter she hooked harmonious rugs and made quilts, spreads and cushions all of her own designing. One could read her touch and see her handwork in every corner of the livable old place.

—

- Over the oak chairs of the mission furniture period lay the weathered quilting frame, pierced at regular intervals by auger holes. Patricia helped stretch the downy lining over the frame, helped whip it into place with a large darning needle and cord. “I have never seen a quilting frame before.”

- “Father made this for me when we were first married. I’ve loaned it over the country-side so that every bride in this section has gone out with at least one quilt for luck made on it. Nobody seems to have frames any more. Let’s see: this frame is now over forty-five years old. And I’m past seventy-five. Help me spread out the wool, Patsy. I carded it myself. Wool left from the time when we raised sheep.”

- Deftly the grey-haired woman with her wise wrinkled face moved about pushing and poking the wool into place. She glanced approvingly at Patricia. Her bird-like listening, daintiness, tact and merry laugh had won Mother Brunhilde. For her own sake, as well as for Martin’s she wanted this girl to become Martin’s wife. [36]

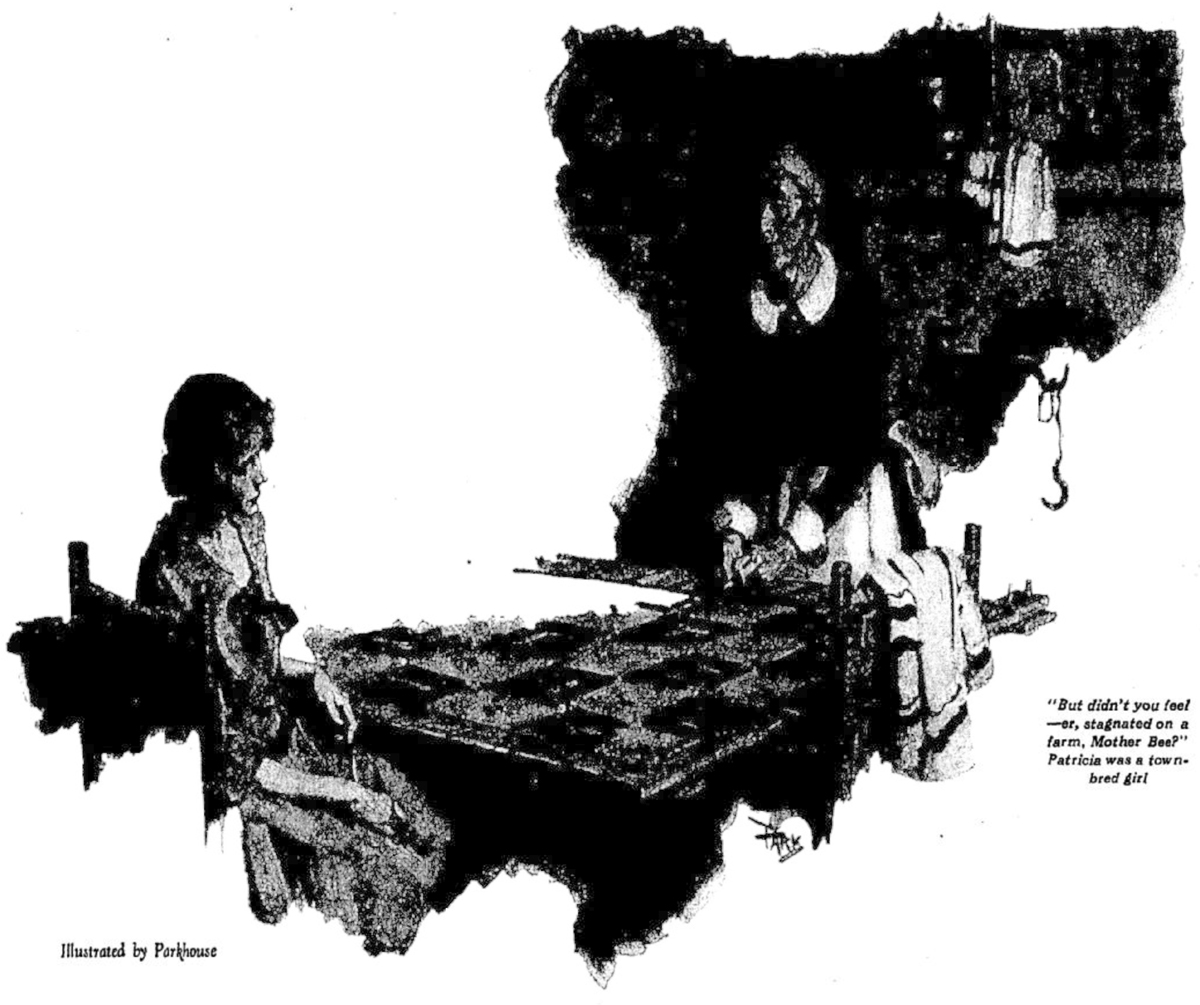

- “But didn’t you feel — er, stagnated on a farm? At first, I mean, when you were younger. I mean that you have so much energy, Mother Bee, and farm life runs on and on so mechanically —” Patricia was a town-bred girl.

- “Help me stretch the quilt over the wool, Patsy. This log cabin is made of Martin’s things: those plaid silks, his boyish Oxford ties, those colorful silks, his later choices. It is for his bride.”

- “H’m?” Patsy looked down and stretched assiduously.

- “Now we’ll pin the log cabin in place on to the lining. Stretch it a bit more, Patsy. When we first started out, John and I — that is, when we lived over the store, I stuffed my patchwork quilts with washed out woolens and old sweaters instead of wool —”

—

- “You were a regular pioneer, so I have heard, Mother Brunhilde,” murmured Patsy, her mouth full of pins.

- “At least father was. He came here a few years before me.” She moved to the sideboard and tore off another row of pins. “Fargo was then only prairie, and Minneapolis and St. Paul not much more than trading stations —” She broke off to say, “We’re ready to tie now with the yellow yarn for contrast.”

- They threaded their long slender darning needles with the yellow yarn that lay like a fleece of gold a-top the dark silks of the blocks.

- Patricia’s eyes wandered over the cheerful room; the waxed oak floors, the two tone taupe rugs, the cheery chintzes of the wide bay window, a bay window affording vistas over the inviting lawn and distant hills. A tapestry wall paper came up to the old-fashioned plate-rail, and above that was a mellow pine-paneled ceiling. On the sideboard and built-in cupboards stood a wealth of old dishes, copper kettles, and relics of Norse origin.

- “Tell me more about old times, please. I love to listen.”

- Mother Brunhilde went to one end of the quilt, put her head on one side and calculated, “We ought to have four knots, don’t you think, in the center of each block, and then four farther out? You tie opposite me —

- “Old times? Um — Father and me, we came from the far North, the midnight-sun section of Norway. Not a prosperous district, fishing was its main industry.

- “I remember when he proposed. We were in a big snow house, an ice palace, the boys who had built it called it. And the young people, with their wraps on, and cheeks glowing, were dancing to accordion music. I wanted to dance, too, but I didn’t, for I was Pastor Klovestad’s daughter. Then father — John — came in and stood by me silently for a time watching the strenuous old Norwegian dances. He was not as striking looking as some — more like Martin.

- “Unexpectedly his slow words came, intimately and close, ‘I’m going away, Brunhilde, to America. I love you. Won’t you wait for me? Until I make a little place for us over there? And then I’ll send for you, and we’ll be married?’

- “John was just a fisherman’s son, and had never shown me any attentions. Instead, I had been keeping company, somewhat, with the young schoolmaster. It was he who had taken me to the boy’s ice palace. But now I forgot the schoolmaster completely.

- “I whispered, ‘I will wait.’

- “He came closer. Under cover of his big scarf his hand slipped over mine. ‘I am starting with nothing. I hope it won’t be long, but I want a home for you. I’ll send for you as soon as the home is started.’

- “I was sixteen then. It was five years before he sent for me.”

- “You were very much in love, of course.” Patricia cocked her dainty blonde head and examined Mother Brunhilde’s wrinkled face: a parchment on which one could read the story of past struggle and pains, as well as joys and present peace. Her fine illuminated face made wrinkles desirable, just as a master’s writing gives parchment worth.

- Mother Brunhilde held a needle to the light so that she might thread it.

- “I thought I was. But what can a girl of sixteen know of love? That is something that grows with the years. Not passion, I mean, but the ripe love I feel for John. I trusted him, of course; he looked solid, reliable and kind. And there was, perhaps, a glamour about him because he was setting off over unknown seas to make his way. No, love is something that grew for me like the blocks of this quilt, a fabric of sunshine and shadow, made into a pattern by one purposed plan.”

- Her bright eyes, absorbed in the past, softened. “I sometimes think of the farm as the final test of love. There human beings are so closely thrown together, so inter-dependent, so united — or smoulderingly antagonistic.”

—

- She had reached the end of her row. She cut her thread and began to work back on the next row of knots, regularly, evenly. “Let me show you how to tie my kind of knot, Patsy. It holds, and the effort of making is less. Bring your needle through the goods once, as you always do, loop the yarn around, and bring your needle through again. Pull, and the knot ties itself.

- “I was saying? Oh yes. Finally John wrote. Then I likewise crossed the fjords and the Atlantic in a sailboat. It took me ten weeks from the time I left home. A girl of twenty-one who could speak no English.

- “John had driven his ox team across the prairies to St. Paul to meet me. I laughed and cried in a breath. We could find no Lutheran minister so we were married by another Protestant minister at the station. Then began our wedding journey back to the farm; nearly a two hundred and fifty mile trek across country with an ox team. On this journey I saw my first buffalo herd, my first band of wandering Indians —

- “I am ready to roll my side of the quilt, Patsy. Unloosen the cord from the frame. And then unloosen the clamp. Now, not so fast, and we’ll roll it up together: once, twice and again. Can you fasten the clamp yourself, or shall I help you?"

- The quilt was now perceptibly smaller. The corner of the oak dining table showed underneath the frame. Once more Patsy perked her head sideways in listening attitude.

- Mother Brunhilde continued, “And at the end of our trail we came to the ruins of John’s carefully built log cabin. It had been burned to the ground. Some drunken Indians had broken into it, so our neighbors said. There was merely the foundation left. ‘I — I waited five years until I was a landowner with a house to offer you, Brunhilde,’ John gulped as we stared at the site. It was a pretty site on the edge of the hardwood timber, the lake in front, and rolling prairie behind it.

- “‘Never mind,’ I consoled. ‘We’ll live in the schooner.’ It was fall and cold snaps were making the nights icy. But we lived in the prairie schooner until Christmas time. I helped build the cabin, chinked it in with moss and clay, and whitewashed the interior. John had to trek to Alexandria, nearly one hundred and fifty miles away for all his supplies.”

- “Was it here?” asked Patsy.

- “You can see it from here. That section near the lake that is now Martin’s farm.

—

- “A couple of years after, John worked on the railroad, the Northern Pacific that was laying tracks out our way. Our crops had failed, and there would be money needed for a doctor, for my first-born was to arrive that winter.

- “I held down the claim. During the days I worked about the place in overalls. I gathered a big supply of dead wood. I chose it because it chopped easily. I carried water from the spring, and took care of the cow and chickens and pigs. It was a cold, snowy winter and a pack of famine-stricken wolves came down from the North. I shot nineteen that winter. One night I sat by the kitchen window with a gun leveled through the crevices, waiting. When the moon came up, the wolf pack skulked out of the timber attracted by the meat smell in the shed entry. In the morning there were seven dead wolves by the kitchen door.

- “Deer often came into the farmyard. Elk also. They were a nuisance for they would eat of the hay that we had stacked for the cows and oxen.

- “I determined that our second child should not be born thus — on the frontier with John away. Besides, we needed money to keep the farm going. So the next winter we hitched up the ox-team and trekked off to Glyndon, where the railroad had erected a big settlement house for the colonists. Glyndon, they predicted, was going to be one of the largest cities of the midwest. It is you see, a sleeping village of five hundred.

- “There, mostly on credit, John and I started a store for the settlers. With the advent of the railroad they were coming in fast. I took in boarders besides caring for the children and the house and helping in the store. After supper John and I would go downstairs — we lived in the second story of the rickety building that we had rented — and there we would work over the books by the yellow flare of a kerosene lamp.

- “John gave everybody credit and stocked them out from our limited supplies for their homestead ventures. Some, terrified by the rawness of the country, and the first two hard blizzardy winters, sneaked away and never paid. In the fall John used to drive out collecting — he had a horse now. He would come to town after a day’s collecting, with a pig or two in back of the wagon, piles of wool, crates of chickens, or driving a small herd of cattle before him.” She glanced at the intent Patsy.

- “You take too long a thread, dear, that’s why it snarls —”

- “What was your home over the store like?” Patsy wanted to know.

- “There were only two rooms; the big front room that I had curtained off to [37] make bedrooms, and the kitchen. The entire poorly built store building rocked like a boat in the hard prairie winds. Then we preferred to go outside. The only stairway to the place was an outside one. It would grow fearfully slippery and ice-crusted in winter, for we had to carry up and down every speck of water.

- “Saloons sprang up on all sides of us. Both Indians and white men reeled through the muddy streets. Fights were constantly in progress. Guns sometimes barked and then the street suddenly grew empty. Sots, like dead logs, lay heavily under my clothes lines in the back alley.

- “No, not the best place to bring up children, so we went back to the farm. John had been renting it on shares to a neighbor — we had proved up the winter we left. And on the farm the rest of the children were born.”

- “And were you always content here? Didn’t you feel, sometimes, that you had missed a part of life? Was there no other love affair that would have taken you to the city, for instance.” Patricia was determined to find a great purple patch of passion or revolt in Mother Brunhilde’s life. Pioneer life was, of course, absorbing. But had she not missed contact with people, for instance. Had she not missed a real love affair instead of a commonplace love “that just grew with the years.”

—

- Mother Brunhilde laughed, her wrinkled face alight. “Stretch the wrinkles out, Patsy, before you fasten the clamp. You mean you wonder if I had any chances that would take me to another sort of life?

- “There was Handsome Jack of a titled house in England — he came with the English colony. He boarded with me during our first winter in Glyndon. He sidled up to me a bit and would have it that we were in love. On the strength of this knowledge of his he went and borrowed five hundred dollars from John to take me away with him. He told father that I needed it for something that I did not care to ask him for. He could always plead a strong case. Father gave him the money without question — although he became very silent, and I frequently saw him staring at me. Then the graceless rascal first announced his intentions to me. He was all ready, tickets bought and everything, to take us back to England. He said that he couldn’t stand it, that the land was a bit too raw for a civilized person. He was sure that his father would accept me. And I could get a divorce.

- “Father and I were minus five hundred at a time when we needed it most, for he skipped out, without returning it.

- “No, I have missed nothing. John and I just kept growing closer to each other. The farm does that for one, I think. Someone ought to write a book on ‘Great Romances of Farm Life.’ He was solid gold, was father. It is worth waiting a great deal longer than five years for a man like that. Love isn’t just meeting and looking. It’s living —”

- “That’s what I say.” Patricia raised her blonde head to confirm the opinion. “I want life.”

- The light had been lit behind Mother Brunhilde’s face. It glowed through her every feature. “When you can find someone with whom you can live with all the strength that’s in you, even if he does drive you out of a placid life into suffering as well as joys, out of crowds to the concentrated essence of life among a few, wait for him five years, ten years, a life-time.” Then she smiled matter-of-factly. “I agree with you, Patsy. We both want life. It can be found in town or country. But found best with the man you love; best in the place where he has complete realization.”

—

- Patricia’s head was bent. She was thinking of Martin. Always when Mother Brunhilde spoke of her John she had unconsciously substituted the name Martin. And Martin had filled the part every bit as well. In fact Patricia was inclined to believe that he could better John. The woman of the story was, at the last, not Mother Brunhilde but herself. She had been living vicariously pioneer scenes, tasting farm life and finding it good. She looked out of the window across green fields to where Martin’s farm lay by a spangled sheet of silver. Why had she thought that “living” was a herd habit, “life” to be found in crowds alone?

- “We’ve nearly finished the quilt, Patsy." Mother Brunhilde smiled across at her. “Our hands are touching on the knots in the middle row.”

- Patricia also smiled into the bright eyes so near her own and rushed into speech. “It is easier living on the farm today, is it not, with the radio and the automobile bringing the town near, with other conveniences at hand?”

- Mother Bee nodded. “But the great struggle goes on.”

- “I know. A yearly sowing of life in germ seeds that ripen into crops to fill the granary bins of the world. A seasonal wrestling with a primitive nature. I don’t think I realized.”

- The fading glow of dreams that were past was in Mother Brunhilde’s eyes. “I think that we, of the country, are much closer to the pulse of real life — I do not mean jazz life — but the pain, the struggle, and the birth of life — the throb of a raw new-born life before it is clothed —”

- She sighed. “The quilt is done. I’ll snip it loose from the frame. Ring for Helga to bring in afternoon coffee, will you, Patsy? Or call her.”

- But Patsy did not seem to hear. She was staring through the wide bay window down toward the swelling red barn and the garage. “Martin is taking out the Chrysler. I must see him at once. I have something to tell him.” Mother Brunhilde watched her go and the ache came back for Martin. And yet she didn’t blame Patsy. It was just the age.

- She watched Patsy’s swift little rush, like a fledgeling’s flight, over the lawn. An interval. Then she saw the two come swinging back toward the house hand in hand. She heard Martin’s deep, happy bass voice.

- “Are you sure, Patsy, you’ll like it? Why, darling, do you know I’d rather live there than any place on earth. You don’t know of my plans for developing and fertilizing it, do you? Some day I’ll have to tell you. I believe that I can make it produce more than any farm in the state. And I’ll have to show you the new variety of Northern seed potato that I am developing —”

- Mother Brunhilde called then, “Come in, children. Kaffetid. There’s flatbrod and lefse and cream cake.”

- Martin came in proudly leading Patricia. “We are engaged, mother. Patsy says that she will marry me this fall so we can live on the old homestead by the lake our first winter. Only she made me promise her that I would keep the wolf from the door — ”

- “I said, ‘wolves from the doors and windows,’” laughed Patsy.

- “Then Patsy will claim the log cabin,” said Mother Brunhilde, a glad light illuminating her withered parchment face.

![]()

paragraph 66 is the key passage (the author’s affection for her parents comes through in this story as well as her earlier “See-Saw”) —

Patricia’s head was bent. She was thinking of Martin. Always when Mother Brunhilde spoke of her John she had unconsciously substituted the name Martin. And Martin had filled the part every bit as well....

19 August 2025