notes and recollections

18 December 2022

Here are notes, footnotes, examples, digressions, &c., &c., to my presentation on and around telegraphic codes — a conversation, really — with the Tender group – link — at MassMoCA on 19 November 2022.

I will add to this page, as time and energy permit.

Some of these (and other related) resources are also bookmarked at pinboard

John McVey

sections (to be reordered)

Traveler’s Vade Mecum

some basic ideas

for the present emergency

code switching

words liable to error

ekphrastic telegraphy (including rag trade and steganography)

fine shadings

what is made invisible

some literary dimensions

Gertrude Stein connections — Short Sentences (1932)

putterings

A. C. Baldwin, Traveler’s Vade Mecum (1853)

I hadn’t intended to, but started with A. C. Baldwin his Traveler’s Vade Mecum (1853), because (1) issues of dis-ability and accessibility are in the air; and (2) Baldwin had served as “Family guardian” (a kind of chaplain?) at the Deaf and Dumb Asylum, Hartford in the years 1847-1854, and thus would have been aware, at the very least, of theoretical and practical discourse about language at the time. My supposition is that that experience was in the background of his telegraphic code (however impractical it may have been).

For a summary of his work and career, compiled with what resources were available to me at the time (2010), see A. C. Baldwin, pastor, telegraph lexicographer, poet : link

some basic ideas

- writing by selection (from an array of options, arranged in lists and tables)

aside —

thus, writing not from some inward flow, but from a visible and external menu of options; the word “ergodic” (step-by-pathway-step procedures, a substitute for cybertext* writing that was common a decade or two ago, comes to mind) - the necessity of drift, a kind of negative capability, whereby the particular nature of a given code will determine what might be said, and how

- codes are constructed from a corpus of actual messages/letters, as if a concordance

- from those “message molecules,” so to speak, additional phrases are interpellated

- phrases are arranged in a combination of alphabetical and thematic order (like a thesaurus), and in tables.

- the codes are always subject to amendments, augmentations, retirement of some sections, introduction of new ones as the needs arise

- the most intensively used codes, whether private or published, are live documents (until superseded by new editions)... and still alive, for some of us users, today.

for the present emergency

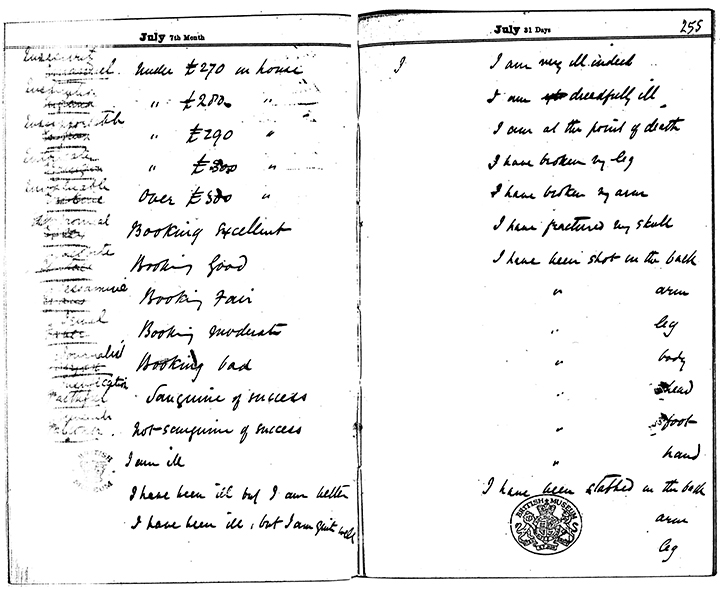

It was common — at least among some — to be able to fashion a short code, in short order, for any situation in which only a few phrases would suffice. A couple of examples are shown below.

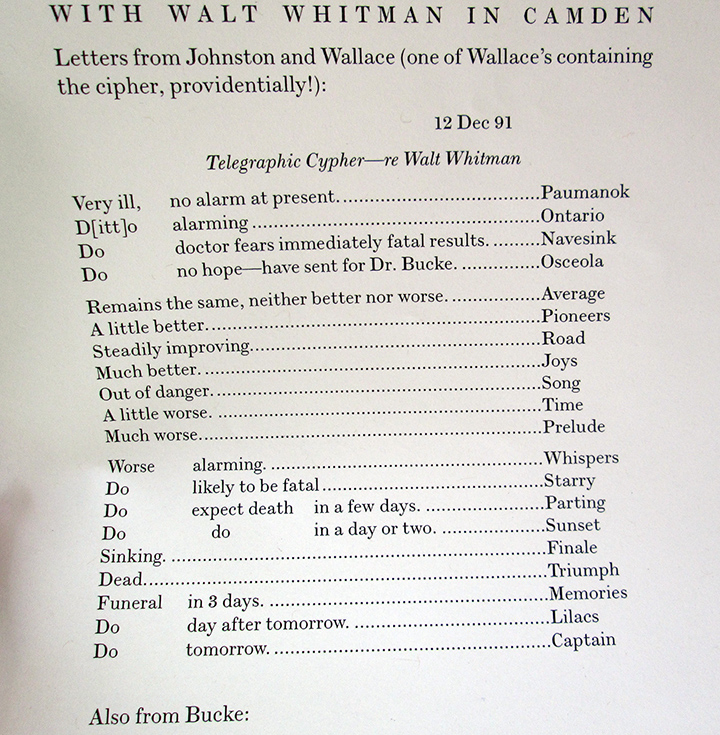

from Horace Traubel, With Walt Whitman in Camden, vol. 6 (?), 1914

from Telegraphic Code for the American Tour of 1879-1880, Gilbert and Sullivan (BL, TS 25, Film Reel 9)

Here we see Gilbert (or Sullivan) letting go, the phrases progressively untethered to likelihood. The full sequence of pages with the telegraphic code : link (pdf)

aside

the phrase “for the present emergency” is taken from Edward B. Bayley correspondence ca 1898, during a period of problems with bookkeeping and some irregularities in the company’s Merida (Yucatan) office. A 4-page letter dated June 29, 1898 is followed by this undated page [p25] :

Special code words for the present emergency

| TORTURED | J. M. Brown |

| TORTURING | Tappan |

| TORYISM | Andrade |

| TOSSED | Gonzalez |

| TOTALLY | Mateo |

| TOTTERING | Mr Peirce |

| TOUCAN | Browne has explained the matter satisfactorily |

| TOUCHED | Browne cannot explain the matter satisfactorily |

| TOUCHING | ........ has cleared himself from suspicion |

| TOUCHHOLE | ........ is implicated in the irregularities in the books |

| TOUCHSTONE | The case is actually short to the extent of about ... |

| TOUCHWOOD | The cash is now all accounted for with the exception of that taken by Tappan and already reported. |

- Edward B. Bayley letterbooks, 1897-1932, 1897-1932.

Henry W. Peabody & Company records, Mss:766 1867-1957 P352, Volume: HL-3.

Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard Business School, Harvard University.

https://id.lib.harvard.edu/ead/c/bak00127c00091/catalog

Accessed December 16, 2022.

code switching

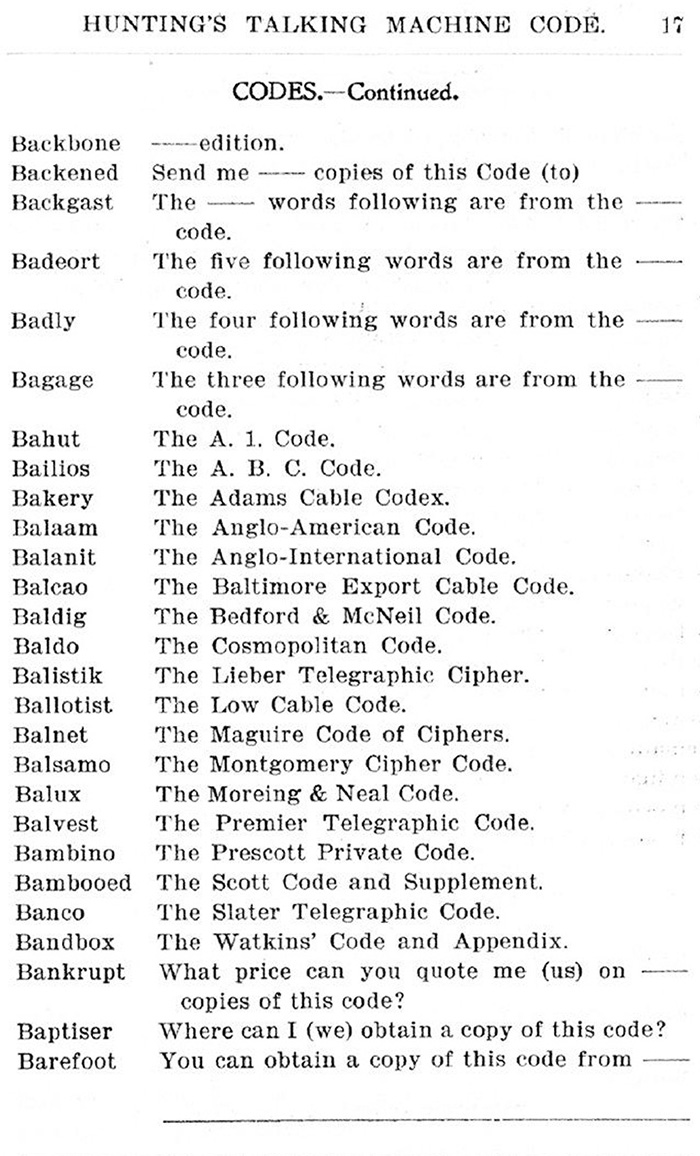

ca 1910, someone might have intuited the expression “code switching” to mean the prompt, within a coded message, to turn to a different code for the following x-number of codewords. This would typically be found in private (so-called “branch” or special) codes, that were focussed deeply on a single domain (e.g., hemp and sisal), and that might even be designed to work in conjunction with a larger and more general code (e.g., Lieber’s).

source : Gallica (BNF copy) : link (see preceding page as well)

ex Hunting talking machine telegraphic code. Compiled for the talking machine trade and useful in mercantile lines where code telegraphy is desired. Including a complete and classified list of each and every separate part of all talking machines (and accessories) yet invented.

Compiled by Russell Hunting (for the Bettini phonograph laboratory). 1898.

a description, and some excerpts, from page on “catalogue” codes : link

One also finds mixes of plaintext and code words in the same message; I don’t know how these would have been treated (charged) by cable firms.

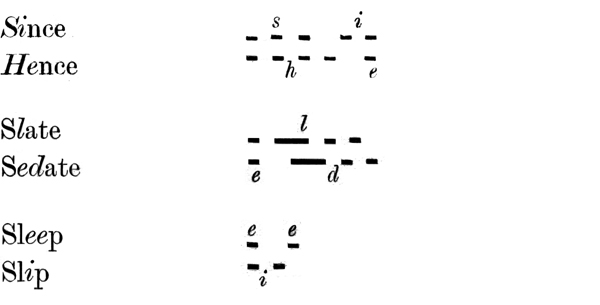

words liable to error

several asfaltics posts, being selections from Part I, “Words Liable to Error being identical in telegraphic signals,” in Guide to the Correction of Errors in Code ( and other ) Telegrams. Fourth Edition. London, 1890. link

Much can be said — and was said, and written, in regular conferences of the International Telegraph Union, of what were acceptable code words. How many letters? Words in dictionary languages? which languages? nonsense/artificial words, but pronounceable (often termed “euphonic”)? relation of vowels to consonants? two-letter difference? etc., etc. I pass over that without getting into the weeds, but note that the evolution of codewords (from long words, offering built-in redundancy) to the five-letter codewords that gradually came into use in ca 1910, and were quite common in the 1920s, was enabled by constant improvement in cable (including wrapped "permalloy" cables) and terminal technologies (automatic sending and receiving, precise synchronizing in time-division multiplexing, introduction of vacuum tubes, etc.).

Title page, BL copy of the New Official Vocabulary for Telegrams in Preconcerted Language, vol. 1 (of 4), (1899-1901)

all four volumes available via hathitrust : link

The “new” official vocabulary contains some 1,176,100 code words, plus several hundred (thousand?) in an appendix contained in volume 4.

aside —

“Dada denounced the infernal ruses of the official vocabulary of wisdom.”

— from Jean Art, “Dadaland,” Ralph Manheim, trans., from On My Way (1948, from an earlier source, 1938)... anthologized here and there, including Lucy R. Lippard, her Dadas on Art: Tzara, Arp, Duchamp and Others (2007) : 28 : link

ekphrastic telegraphy

Under this heading are methods of analyzing and coding visual or topographic information, that are not automatic but involve interpretive actions of a human. Such methods are distinguished (more or less) from automatic methods such as phototelegraphy (involving selenium cells) or eventually facsimile (telefax), and that also relate to television and later digital image processing.

Ekphrastic telegraphy would cover map/battlefield codes, fingerprint codes, police codes, fashion codes (for the rag trade), and even astronomical and meteorological codes (describing clouds, for example). Descriptions of (and links to) some of these latter can be found via their respective headings at the overview (directory) page : link.

some other sources are listed (and linked) below.

- US68088 : “Improvement in Transmitting Plans of Battlefield by Electric Telegraph.” Thomas W. Knox (1867) : link

- “The Targets at the International Rifle Match.

Diagrams showing the Shots made by each contestant of the American and Irish Rifle-Teams at Dollymount, Ireland, June 29, 1875”

in entry for “target,” in

Knight’s American Mechanical Dictionary: A Description of Tools, Instruments, Machines, Processes, and Engineering; History of Inventions; General Technological Vocabulary; and Digest of Merchanical Appliances in Science and the Arts... Volume III. — REA=ZYM. (New York, 1877) : link

based on — - “The Targets at the International Rifle Match.

Diagrams showing the Shots made by each contestant of the American and Irish Rifle-Teams”

“A new feature of journalism — the shots made by the riflemen at Dollymount, Ireland, accurately shown by cable, through a process invented by the Tribune correspondents...” in the New-York Tribune (June 30, 1875) : link : (pdf) - W. E. Zuppann. “Pictures Sent by Wireless.” Illustrated World 26:5 (January 1917) : 678-680 : link

- “Telegraphing Photos by Code” in Science and Invention (“formerly Electrical Experimenter) 8:9 (January 1921) : 967, 1010 (page links to hathitrust)

features system of Thorvald Andersen; “the original photograph or sketch has first to be accentuated by an artist, so as to represent a decided contrast between light and shade...;” uses grid :

Code message necessary to transmit portrait : hair and contour X6 to Z, W7 to Z, O6 to U, V8 to Z, O9 to T, U9 to B8, O10 to BB, N11 to Z, B5 to DD, M12 to AA, B5 to DD, etc. [transcription not guaranteed, from inexact scan]aside —

The above is incorporated into Chapter 5, “Telegraphing Photos by Code” : 22-29 : link (pdf)

(followed by Chapter 6, “Direct Wire or Radio Picture Transmission (Codeless)” : 30-59

in “All About” Television, Including Experiments, by H. Winfield Secor (Managing Editor) and Joseph H. Kraus (Field Editor) of Science and Invention (1927) : this was a special issue of Hugo Gernbsack’s Electrical Experimenter (something about it) and is listed, among other available issues, at this World Radio History page : link

- series of articles on “telegraphic sketch diagrams,” and later obituary of W. H. Wisner, from the Chicago Tribune:

Telegraphic sketch diagrams of the knockdown and knockout (July 3, 1921)

First perfect knockout pictures ever sent by telegraph (July 4, 1921) [comparison of photograph and sketch]

Wreck of ZR-2 [Zeppelin] in the River Humber (September 5, 1921)

“Wire picture” of Jersey City scrap (September 6, 1921)

W. H. Wisner, Tribune ex-Art Chief : Noted for Color Maps of World War II (December 12, 1963)

composite pdf : link - D. W. Isakson. “Developments in Telephotography.” Journal of the AIEE 42 (1922): 811-818 : link

- GB190522 : “Method of and Means for Reproducing Pictures and the like, at a Distance by the use of a Signal Code.” Thomas Francis Gaynor (London). December 18, 1922) : link

- US1538916A : “Method and means for telegraphing photographs.” William Henry Wisner, Assignor to the Tribune Company of Chicago, Illinois (May 27, 1925) :

link

shows grid, barn, instructions for coding, exampled thus:

“Roof ridge begins 6G2 extends left and down to 9C2. Then slopes to left to 19A2. Left eaves extend from this point up to 17E1 then up to start. Right slope of roof down to 18J. Ground at left of side wall begins at 30A2 irregular to left front corner at 35E1 then to front right corner at 34J.” - US1581937A : “System for transmitting graphic illustrations.” Le Roy J. Leishman (April 20, 1926) : link

shows grid, sketch of airplane

The “telegraphic sketch diagrams” of the Chicago Tribune (and Wisner’s 1925 patent) involve the intervention of (1) a coder and (2) a skilled illustrator, who can translated the abstracted (coded) language into a convincing image. I think this is where the expressive nature of ekphrasis enters (my) picture —

-

Ruth Webb. “Ekphrasis.” The Dictionary of Art (Grove’s Dictionaries, 1996), vol 10 : 128-131

“An ekphrasis can be characterized as an extended description of a rhetorical nature. The author displayed his skill with words as well as expressing the qualities of the work described. An ekphrasis generally attempted to convey the visual impression and the emotional responses evoked by the painting or building, not to leave a detailed, factual account. In an ekphrasis of a painting the author did not confine himself to the specific moment represented but was free to discuss the general narrative context, referring both forwards and backwards in time. He was also free to imagine what the characters might be feeling or saying and might even by moved to address them. Since ekphraseis in antiquity and the Byzantine period were often composed for special occasions, to honour the patron, architect or, more rarely, the artist, they set out to praise, not to criticize. The value of ekphrasis as a source for archaeological reconstruction is therefore often limited, but it can provide some indication of contemporary responses to art.” - Ruth Webb. “Ekphrasis ancient and modern: the invention of a genre.” Word & Image 15:1 (January-March 1999): 7-18

“So not only is ekphrasis not conceived as a form of writing dedicated to the ‘art object.’ but also it is not even restricted to objects. It is a form of vivid evocation that may have as its subject-matter anything — an action, a person, a place, a battle, even a crocodile. What distinguishes ekphrasis is its quality of vividness, enargeia...” (13)

“Enargeia is at the heart of ekphrasis.” (13)

See also the patents listed at elementary signs : pictures 1 : link

rag trade

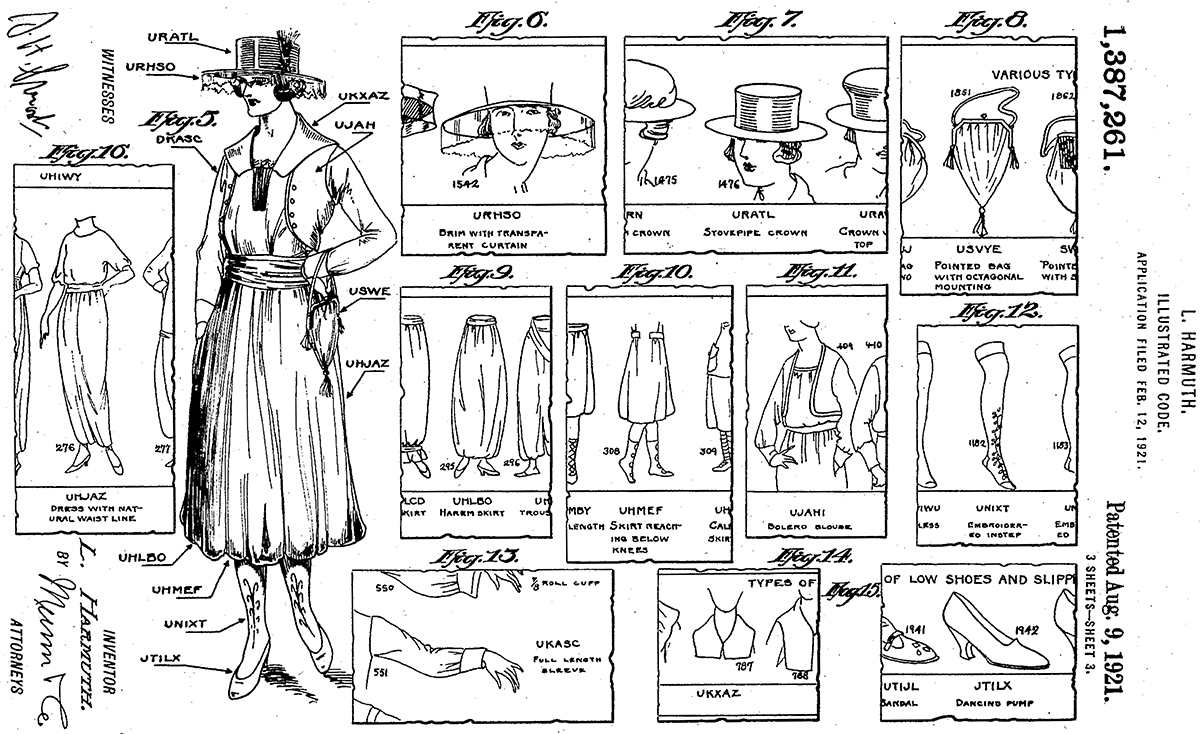

Drawing sheet 3 (of 3), US Patent 1,387,261 (1921), Louis Harmuth, Illustrated Code : link

The above patent underlies (and is an explanation of)

Fairchild’s Illustrated Women’s Wear Code / For Manufacturers, Importers and Distributors of Coats, Suits, Dresses, Blouses, Waists, Skirts, Lingerie, Negligees, Corsets, Millinery, Hosiery, Footwear, Gloves, Handbags, Parasols, Fabrics, Etc.

With over 2,200 Illustrations / 45,000 Code Words

Compiled by Louis Harmuth / Technical Editor / Women’s Wear

First Edition. Fairchild Publishing Co. New York City. 1921

(taken from title page)

8.75 11.25 inches

- Section I. — Commercial Conversation Part (pages 5-285)

- Section II. — Fibers, Fabrics, Feathers, Flowers, Furs, Colors, Historical Periods, Countries (pages 286 to 300)

- Section III. — Illustrated Part (pages 301 to 416)

The introduction describes these advantages offered by the code, beyond the ordinary objective of reducing cost by an “abbreviated and condensed form of conversation.” —

- Through the illustrated section of the Code, it is practically possible to wire or cable pictorial representation of ideas. Since each illustration has a Code word, the receiver of the message, upon decoding it, is enabled to visualize the same thing which the sender actually saw or had in mind.

Speedy communication of new ideas and developments is such an important factor in the women’s wear industry of the present age, that the value of cabling pictures will be appreciated. This Code also saves the incidental expense of engaging artists to make sketches and the time required to have them made and sent. - The illustrated section can be advantageously used even by parties who do not find occasion to cable or wire. In ordinary correspondence, for instance, a simple mention of the Code word for some of the sketches would show the recipient the idea in more eloquent form than any description could possibly accomplish, besides saving the expense of art work.

- Through the illustrated section, two parties are enabled to send each other ideas relating to women’s garments, even if they do not speak each other’s language.

- This is the first complete Code written exclusively for the women’s garment trade and industry.

A copy of the above is at NYPL.

I have not examined a “pocket size” Fairchild Code for the Men’s Wear Trade (1910), 210 pages, that is evidently at the National Cryptological Museum (Fort Meade, Maryland). Brief description in the Textile World Record 40:5 (February 1911) : 156 : link

Fairchild’s Illustrated Women’s Wear Code has turned up, on a couple of occasions, in asfaltics confections : link

steganography

Steganography is perhaps a sub-category of ekphrastic telegraphy? Or a strange reversal? where the picture contains hidden words? Or is suspected of it? One example is presented below.

“A Graphic Spy Code.” The Literary Digest (February 9, 1918) : 30 : link

...instead of being merely cubistic...

Modern art has played into the enemy hands in a way such as the art of the past could never have been guilty. The technique of our modernists has accustomed us to many lines and strokes that to the uninitiated seem at best irrelevant and at worst the attempts of a tyro who fails to say easily what he aims to impart. But the watchful and resourceful German spy finds in them a camouflage for his code-message, and so he sends to Germany by way of Spain information about our defenses in the Caribbean. And it all goes as part of the design of a magazine-covered issued in Porto Rico. The artist and plotter, Werner K. R. W. Sturzel, is safe now at Fort Oglethorpe, where he admits that he is a special intelligence agent of the Imperial German Government assigned to get information to Berlin. The New York Tribune gives a reproduction of the magazine-cover, and says:

“What is believed to be his most ingenious trick to get secret information to Germany via Spain was in the form of a line-and-wash drawing he made for the Puerto Rico Ilustrado in 1917, and which appeared as the cover-design of that periodical in the issue of January 5 of this year. This paper has a large circulation in Spain, and Sturzel was aware that, through no incriminating effort on his part, his cryptic illustration would fall into the proper hands in Barcelona, Valencia, or Cartagena, and eventually reach the German destination.

“Although Sturzel posed as a business man, he was exceedingly versatile, and used his talents to further his espionage activities.

“Painting and drawing were among his accomplishments, and by the aid of his talent he managed to create for the Puerto Rico Ilustrado the head of an Arabian woman, entitled ‘Tipo Arabe,’ which the Porto-Rican authorities believe literally teems with code letters and hieroglyphs decipherable only in Germany or by Sturzel.

“Persons familiar with the handling of codes and cryptograms have exprest the belief that in his cover-design Sturzel may have revealed important information to the enemy, especially as to American activities and defenses in the Caribbean. This was given particular significance, since it was known that German agents have been active in their efforts to procure a submarine base in Caribbean and West-Indian waters, and that the Kaiser has many sympathizers in Venezuela.”

Some personal facts about the fabricator are added:

“Just about the time that the Government agents began to lay their plans to trap Sturzel, Cipriano Castro, the ex-Dictator of Venezuela, ws ordered out of Trinidad by the British Government and immediately returned to Porto Rico, where he had made his home for ten months before the United States declared war on Germany.

“Sturzel was sent to Porto Rico about the time the European War began and was employed by one of the biggest German business houses on the island. He always had an abundance of money and was a liberal spender. It was the belief of the Secret Service agents who were watching him that he was in the pay of Wilhelmstrasse. Sturzel gave the impression always that his parents were wealthy and that it had been their custom to ‘give generously to the children far away from home.’”

The original New York Tribune (January 23, 1918) : 3 : link (pdf)

cubism —

“But will the poetry of a bare sign suffice? The future will tell us.”

— André Salmon. “Histoire naturelle des peintres; peintre cubiste,” Gil Blas. September 29, 1912,

cited in Lynn Gamwell. Cubist Criticism. Studies in the Fine Arts: Criticism, No. 5. (UMI Research Press, 1997) : 42

Both “analytique” and “synthétique” are occasionally used separately in cubist literature; however, the use of “synthétique” in the recent symbolist movement may explain the more frequent singular occurence of that term. The terms were used together by writers on cubism to describe works of art, rather than to describe judgments about art or to explain perception as Kant did. What writers inherited from Kant’s usage was the idea of two opposed processes: analysis, the study of objects in nature and breaking them up into basic components; and synthesis, the assembling of distinct parts to make a unique whole.

ibid., 17

fine shadings

on commodities codes (wool, cotton, coffee, etc.), the fine discriminations of grade, quality, different combinations of particulars in requests and offers.

what is made invisible

I concluded (or nearly so) by showing some coded telegraphic communications, that would be invisible in McNeill and other ordinary telegraphic codes devoted to minings. These were messages from managers on site, and investors in Boston, involving the Copper Mine Strike of 1913-1914 in Calumet, Michigan.

- The strike is introduced at www.hu.mtu.edu/vup/Strike/

- the coded telegrams (and their translations) are linked from : http://www.hu.mtu.edu/vup/Strike/telegrams.html

The digression may have been prompted by what is left out of — and rendered invisible by — the mining and wool codes we have encountered (in the latter case, relating to Australia and Tasmania in particular).

Incidentally, the word “visible” is a technical term encountered in some telegraphic codes, especially those devoted to commodities. It refers to supply (in warehouses or on board ships) that is visible, meaning known or declared; the always present unknown risk factor is “invisible.”

some literary dimensions

- ...the to-be-or-not-to-be rumination on the codeword “Interjection” from Anthony Hope his novel Second String (1910) 151 : link

- the abababal / ababedem / ababifin / ababogop etc., codewords of Ludovic N. Bauer his Bauers Code, Der neue deutsche Telegramm-Schlüssel (Leipzig, 1913) : link — versus —

- the dadaistic poetry of the time, e.g.,

jolifanto bambla o falli bambla

großiga m’pfa habla horem...

ex Hugo Ball, his “Karawane” (1916) : link - some more, at a long-neglected page : link

Gertrude Stein connections

A closer look at Stein’s Short Sentences (1932) can be found here : short sentences

Will add something about how Stein and telegraphic codes, respectively, adjusted my mis/readings of each.

putterings

My actual conclusion may have been a digression about the activity of “puttering.”

While I cannot clearly recall how or why, I did fasten onto the word’s appearances mainly in the nineteenth century (primarily in the U.S.: the equivalent term in England is “pottering,” with an o), and proceeded to collect passages containing it.

- puutterings : link.

- Eventually I created a sortable index to those entries : link

which in turn led to - derivations (ongoing) therefrom : link.

This project (a preoccupation of this last year) has also brought into view, for me, some interesting writers, including Florida Pier Scott-Maxwell (1883-1979), e.g., her “The Blessed Ambient” (1909, link) and Milnes B. Levick (1887-1946), his writings (including This Is The Master Race : A Gallery of German Portraits (1945)) listed here.

photo by Justy Phillips; background shows (in addition to my cluttered desktop) code books and clerks, Private Telegram Department, 1923, from Donald Read, The Power of News : The History of Reuters (1999)

18 December 2022

revised (link corrected) 20240127